Solstice

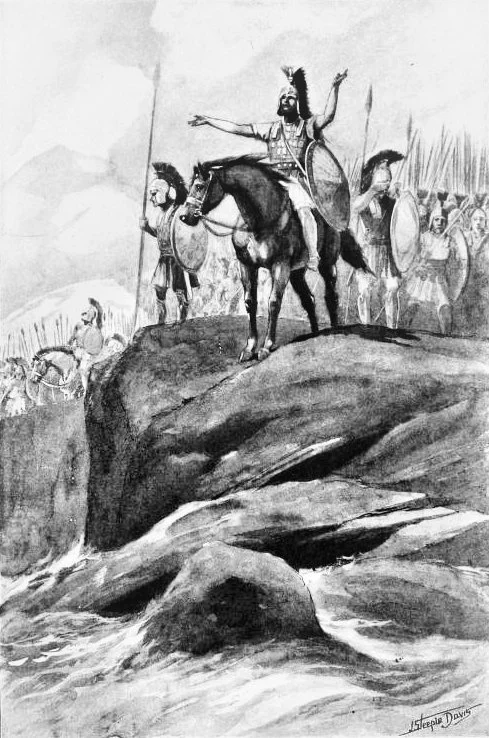

Around 400BC an army of 10,000 Greek mercenaries set off from somewhere near Ephesus on the west coast of what is now Turkey. They were in the pay of Cyrus the Younger, to march eastwards and confront his brother, Artaxerxes, in a struggle for the Persian throne. At the Battle of Cunaxa (401BC) the plan foundered. Cyrus was killed and the army was left to make its way home as best they could. After many tribulations they eventually reached the Black Sea. Standing on top of a mountain they let out a cry…”O Thalassa, O Thalassa!”, ‘the sea, the sea!’. For them the sea meant passage home and safety at last.

‘O Thalassa, Thalassa’

*

In 2015, at Bodrum on the Mediterranean coast of Turkey about 50 miles south of where the 10,000 had set out some 24 centuries earlier, a group of refugees fleeing the bloody civil war in Syria scrambled aboard a small boat hoping to find freedom in the west.

Shortly after it set off, the grossly overcrowded boat capsized. Five people were drowned. Among them was a small boy, Aylan Kurdi, washed up on the shore. The photograph of a coastguard carrying the limp body along the beach became an iconic image of the desperate plight of refugees fleeing oppression and violence in their homelands.

*

It is the Winter Solstice, in the past aligned with St.Lucy’s Day, ‘Being the Shortest Day,’ described thus by John Donne:

‘Tis the year’s midnight, and it is the day’s,

Lucy’s, who scarce seven hours herself unmasks;

The Sun is spent, and now his flasks

Send forth light squibs, no constant rays;

The world’s whole sap is sunk…’

St. Lucy was a symbol of light, often depicted wearing a headdress of candles, thus leaving both hands free to carry provisions for the persecuted Christians hiding in the catacombs.

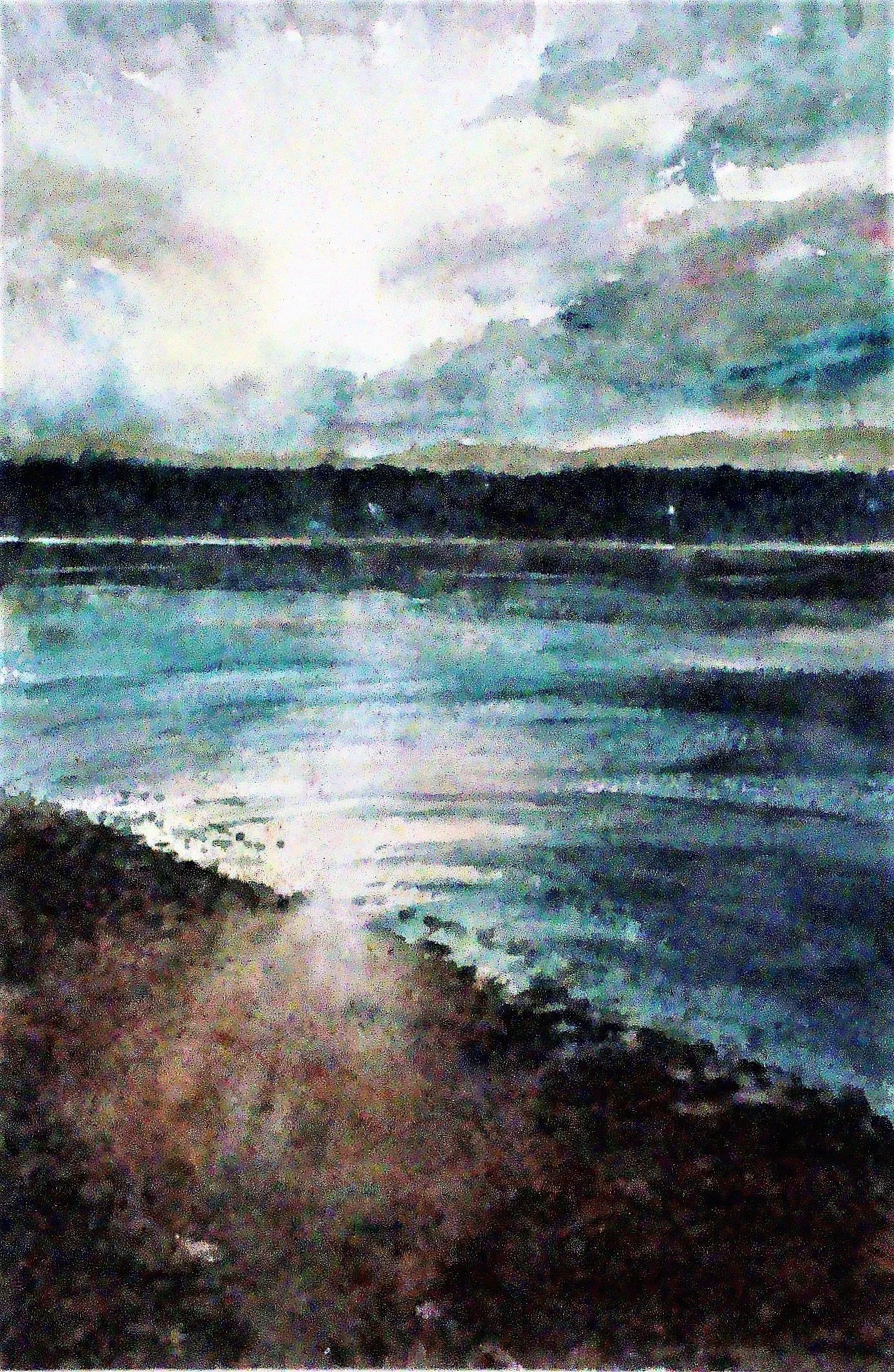

This Winter Solstice — the nadir of the sun’s annual trek, the moment it ‘stands still’ before beginning its climb upwards again — I am walking along the shore to be present at its southern tip and observe the sun at its lowest point. Dunes and rough vegetation to my right, the sea washing in on my left. It is here that I have a strange vision of the waves and the spray coalescing into human forms…

At the lowest ebb of the year

as I track the strandline on the spit,

there they are,

washing ashore, shaping the bubbling foam…

froth-forms…these souls migrating back.

They tumble over each other in waves, scramble

up the shingle and stand bewildered, look about.

One in plastic sandals scurries into the dense buckthorn.

Another, hooded, crouches among driftwood.

Here, a mother, wrapped in weeds,

cradles an infant.

And a boy with a phone cries at the sea

…We thought we would be free

but no, the tide has thrown us back…

I would throw my arms wide and welcome them

but there are ghosts enough in my draughty hangar.

Not that I believe such things, but

on this shifting sandbank, when the sun’s

an ochre smudge in a charcoal sky,

the mind’s a windy place, its echoes cavernous.

Is my response to the lost souls before me too callous? Just a convenient excuse to claim that my mind is haunted by too many troubles of its own to really care?

Following the Bodrum disaster, Brendan O’Neill wrote of the photograph of Aylan, ‘The global spreading of this snapshot is justified as a way of raising awareness about the migrant crisis. Please. It’s more like a snuff photo for progressives, dead-child porn, designed not to start a serious debate about migration in the 21st Century but to elicit a self-satisfied feeling of sadness among Western observers.’

In more measured tones, Nick Logan argued, ‘Photojournalists sometimes capture images so powerful that the public and policy-makers can’t ignore what the pictures show.’

My heart went out to the little boy — and his grieving father — but so what? Was the catharsis of sorrow just an indulgence, a kind of grief-porn of a comfortably off, safe citizen of a prosperous Western European country? Should I feel guilty about my sadness, then guilty about feeling guilty? I’m afraid I must leave that question hanging in the air. I have no ready answer.

*

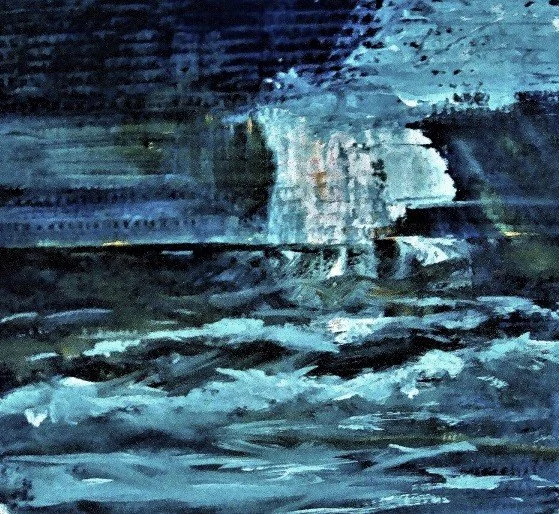

The sea portending hope, a fair voyage, homecoming, safety. The sea whose promise turns to disaster and the dashing of all hope. The sea itself is, of course, completely indifferent. As Guillevic says:

Yes, I have seen you wild, out of control,

before shouldering the assaults of the wind.

I have seen you flouted, seeking your revenge

and wreaking it on others than the wind.

But I speak of you when you are only yourself,

without power except to absorb.

*

The birds who live on or by or from the sea are not immune to its indifference. I remember, after a stormy night, seeing a guillemot floundering near the shore, utterly spent, its wings helpless. And then the remains of a once handsome gull lying amongst the sea-wrack.

Gull

Coming across this makeshift crucifixion

of bleached bone and feather,

its wrecked fuselage and wrangled wings

and the yawning mandibles unhinged,

I wonder what battering

wind or water wall broke

its final back, sucked its flight

askew like a comic umbrella,

try to fathom the mashing of

its marble resistance, the unscrewing

of that eye’s hard purpose

with the quiet tide now lapping

its feet, rinsing the ochre stains,

and a low wind echoing the cry of gulls.