Cats

As I mentioned in my last post I have been reading an excellent little book by Professor John Gray entitled ‘Feline Philosophy’. The theme is that we would be far less troubled as a species if we lived more like cats.

Mabel

We humans are rather unsatisfactory mixtures of instinct and intelligence, capable of the most remarkable invention and creativity whilst at root driven by animal instincts which can lead to the most terrible excesses. Men can make robots the size of a pinhead to put inside smartphones or land a space probe on an asteroid 200 million miles away. Men can also choke the atmosphere with carbon or, if they are so inclined, march into a village in Mozambique and behead fifty of its inhabitants. Burdened with this mix of primal instinct and the capacity to think and analyse we are deeply unsettled. We feel compelled to work it all out, to find the best way to live.

Mmmm…..

To provide ourselves with an answer we invent stories. Religions, philosophies, ideologies are all such stories and if you tell them often enough they become objective truth. This can turn into stone tablets, often in a fanatical way, especially when it is hitched to morality, which it invariably is. We end up thinking that morality — right and wrong, the do’s and don’ts of life — is absolute. But, as Gray says, ‘in the end, all that exists is the multitudinous human animal, with its many different moralities.’ In trying to manage our troubled existence we end up chasing shadows.

Misty, untroubled by lockdown in West Yorkshire

A cat, however, will chase its own tail for the fun of it or because its instinct tells it to pounce on anything that moves. Cats hunt, eat and sleep without fretting about whether they should be vegetarian or be improving themselves rather than lying on the sofa purring. They bring in dead birds much to the disgust of their human owners. They attach themselves to us humans because we give them what they want. They lie on their backs and let us tickle them not because it gives us a weird sort of pleasure but because the sensation satisfies them. We would not lie on our backs and let someone tickle us, not beyond babyhood, anyway.. It would be attended by a faint sense of guilt, that somehow the activity bordered on the immoral. How early in life do we stop skipping and doing handstands!

*

When I was a boy most people had pets and we were no exception. My earliest memory is of a mongrel dog who slept among the dirty washing my mother shoved under the big white porcelain sink until washday. The animal spent most of its time there. A later dog, called Adam, had a matted, shaggy coat which hung in thick hanks from his scrawny body and was impossible to brush or comb. So we periodically sheared him like a sheep.

But to return to cats.

Mabel again

I recall from my childhood a white cat we called Twinkle, though she is but a ghostly presence in my memory. When our children were growing up we acquired two little kittens — they were twins, I think. Josh was ginger and Jesse a tortoiseshell, a delightful, playful pair. Unfortunately we didn’t have them for long. One day they disappeared mysteriously. Despite searching the neighbourhood, making enquiries and scanning the roads for flattened cats, we found no trace of them. As far as the children were concerned, suspicion fell on the Chinese lodger we were putting up at the time. He used to come down every evening to make his dinner in a large sizzling wok. We never quite knew what went into it.

Later I adopted a small black cat from an old lady I used to chat to in the local pub. She had too many cats, she said. So I took the scruffy bundle in. I called it Stanley after the footballer Stan Collymore who at that time played for Bradford City, the team I would take my boys to watch every weekend and whose result is still the first one I look for every Saturday evening even though I now live two hundred miles away. My cat was an impressive dribbler of a ping-pong ball, hence the name. Though cats do not ponder the meaning of life, they are no strangers to fear. A vivid memory of Stanley was him crashing through the cat flap at high speed and hurtling through the kitchen and up the stairs. I looked outside to see a monstrous ginger tom licking its lips and leering at me. On another occasion, after a foul night of wind and rain, I realised I hadn’t seen Stanley for some time. I went out into the street of terrace houses and called his name. I heard a pitiful mewing and traced it to a cavity below a basement window. Stanley had slipped through the grating and was lying on a pile of wet leaves. I took the sodden animal home and convinced myself he was glad to see me. Sadly, my son developed an allergy to Stanley and we had to get rid of him (Stanley, that is.}

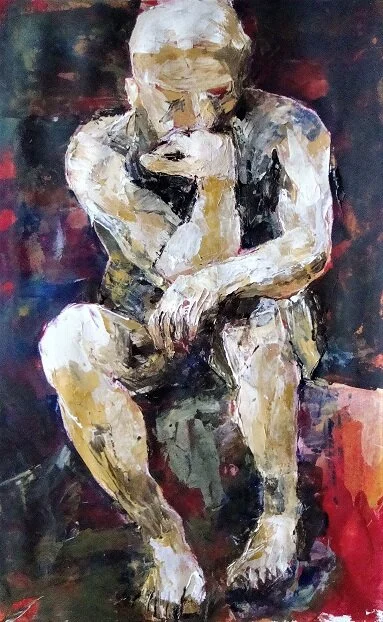

Man deep in Thought

Though I no longer have a cat, two of my offspring have taken one into their homes. My daughter, Kate, and the children share their house with a tabby called Mabel. She hunts for birds and mice and brings their remains into the house. She sleeps a lot, presumably without feeling guilty about it, and sits and watches the world go by with apparent disdain. My granddaughter, Martha, is the only one she will accept being cuddled by.

Mabel yet again

And my son, Andrew — yes, he who was allergic to Stanley — and his family now have a cat called Misty, a little creature like a wisp of smoke. It lives in the house (it is a large house and a small cat) and perches precariously on the top of the banister. Misty replaced a hamster who slept all day and failed to provide the children with much entertainment.

*

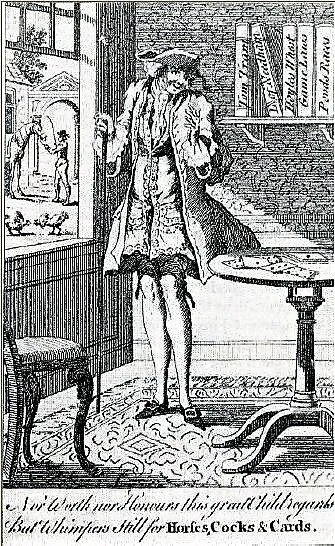

Poor Christopher Smart…’For I will consider my cat, Jeoffrey.’

How easy it is to anthropomorphise our feline companions. The 18th Century poet, Christopher Smart, who spent most of his life either in a lunatic asylum or a debtors’ prison, wrote a poem about his cat, Jeoffrey, who he thought was an agent of the Almighty: ‘he knows that God is his saviour.’ However, says John Gray, ‘Unlike dogs, cats have not become part human.’ Cats have domesticated themselves with humans and live on their own terms. Cats do not think about the meaning of life. ‘Living like a cat means wanting nothing beyond the life you lead. The meaning of life is a touch, a scent, which comes by chance and is gone before you know it.’ So ends the book, ‘Feline Philosphy’, but not before the author offers us ten feline hints on how to live well, which here I take the liberty of reprinting.

1 Never try to persuade human beings to be reasonable.

2 It is foolish to complain that you don’t have enough time.

3 Do not look for meaning in your suffering.

4 It is better to be indifferent to others than to feel you have to love them.

5 Forget about pursuing happiness, and you may find it.

6 Life is not a story.

7 Do not fear the dark, for much that is precious is found in the night.

8 Sleep for the joy of sleeping.

9 Beware anyone who offers to make you happy.

10 If you cannot learn to live a little more like a cat, return without regret to the human world of diversion.

Figures on a Beach

*

I end with a poem. I read in the paper that a headteacher in a particularly bleak area of the North East set about installing various objects within the playground to provide enjoyment and interest for the children — benches, a little pond, wind-chimes, for example — only to discover, one morning, that the whole lot had been smashed up.

The Garden

All summer long in the schoolyard

he has been building a garden,

his plan propped on a board,

the old headmaster with his thick spectacles

and white beard flowing.

There is a waterfall spilling

into a small pool

and the surprise of fish in a blue sky.

Suspended in the young trees,

wind-chimes are clashing, gently

sowing charms in the air.

Chosen stones,

cool to the cupped hand,

are weighed for contemplation..

A feathery light

filters into leafy bowers

inviting the meeting of hearts.

There stands at the end

of a soft gravel pathway

a sundial like a dove.

And the first bell of term

will bring them.

Their skin will bristle like sharpened sticks.

Their eyes will narrow,

splintered glass flickering with fire.

Its knell will bring them

circling each other with khives.