Ingleborough

A few days ago I was walking up Doon Hill, a small outlier of the Lothian Edge standing unassumingly at a mere 600ft beyond the A1 to the south of Dunbar. Climbing up its short, steep slope I realised how I had got out off the habit of climbing hills, and how much I missed it.

When I moved up to Yorkshire in my late teens from the warm intimacies of the Buckinghamshire countryside, a whole new experience of landscape opened up to me — great, wide spaces, high hills, endless expanses of moorland. An hour’s drive would take me south to the Pennine moors and the Peak District, north east to the Yorkshire Moors and the Wolds, or north west to the magnificent stretches of the Dales, with, of course, the fells which rose above them. The most accessible of the dales from Wakefield, where I lived and worked, was Wharfedale and before long I was climbing Simon’s Seat or Great Whernside or, at the head of the valley, Buckden Pike. But as I plodded up Doon Hill the other day my thoughts strayed further afield, beyond Wharfedale, to Ingleborough. At 2400ft, it stands at the western edge of the Dales, beyond Ribblesdale and to the south of Dentdale. Its awesome presence with its stepped limestone scars is an unignorable landmark for anyone driving up the A65 to the Lakes.

Ingleborough from the West

Ingleborough is often grouped together in a neighbourly triangle with Pen-y-ghent and Whernside. Hardy walkers attempt all three and even hardier runners do the twenty-odd miles of the Three Peaks Race annually.

I am familiar with this walk from my schoolteaching days. In the summer term, the senior boys, once they had done their exams, were not as is the current practice set free to go their own way but held captive till the end of the school year. Doing the Three Peaks was one of the activities designed to keep them occupied. I recall June outings when the heat shimmered off the rocks as we scrambled up the steep nose of Pen-y-ghent, the stop for elevenses at Hull Pot, then the long trek across scrubby pastures, by small farmsteads, to the towering viaduct at Ribblehead. Then it was the turn of Whernside, its looming whaleback the highest of the Peaks even though it doesn’t look it. After the steep descent, I remember on one occasion the boys letting off steam splashing around in Winterscales Beck, even constructing a makeshift raft! The final challenge was the precipitous western slopes of Ingleborough from Chapel-le-Dale, up through the rocky scars until we achieved the wide, flat summit plateau. We would stand there and view the panorama — from the lingering industrial haze to the south-east, to the Lake District hills north-westerly, and then the great chain of the Pennines disappearing northwards. Lastly, the gradual unwinding as we descended through the limestone pavements to Horton-in-Ribblesdale where we had started. And then home, with the obligatory stop in Settle for fish and chips.

Pen-y-ghent

In later years, well into my retirement, I continued to venture out to the Three Peaks, not necessarily to do all three but one at a time. Ingleborough became my favourite and my preferred route was from Clapham, a little village between Settle and Ingleton, now thankfully bypassed by the main road. It is pleasing to walk through its narrow streets with their stone cottages and church as you set off, and even more pleasing to return, with the promise of a pint of Black Sheep awaiting at the New Inn.

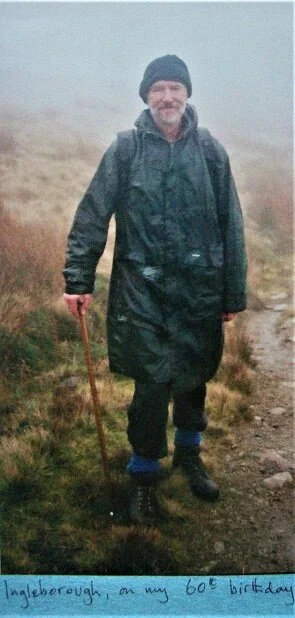

An occasion I remember with particular affection was a walk up Ingleborough on my sixtieth birthday. My son, Andrew, asked me if there was anything I’d like to do for my birthday. ‘Let’s go up Ingleborough,’ I said, so we did. Though I enjoy walking on my own, it was good to have company that day. It was not the best weather, overcast and damp, but what matter. At the top of the village, next to Clapham’s church, we entered a private garden and put 50p in a box for the privilege of walking through the grounds alongside a little lake, a pleasant enough start to the walk. We emerged from the lakeside wood onto a track which led past ingleborough Cave, a labyrinth entering deep into the limestone underworld of these dales. Shortly after, we turned westwards up through the gorge of Trow Gill, its tree-crested cliffs looming on either side. Later, I did a rather modernistic impression of it; I also have a photo of Andrew emerging from the Gill into the open spaces of Ingleborough Common.

An impression of Trow Gill

Andrew emerging from the same

This whole area is pockmarked with shake holes and pot holes the most renowned of which is Gaping Gill. Fell Beck flows into its dark maw, plunging over 300ft into a huge cavern below. It is, of course, compulsory to go and peer down it before continuing on your way. On another occasion, when I was walking alone, I got rather closer to the edge than I’d intended. An extract from my diary for that day reads: ‘Stlll snow on the upper slopes but melting — v. wet and slippery. Looked down Gaping Gill, slipped while crossing the stream and had frightening visions of being swept down the hole! Managed to grab a rock and scrambled out…’ Well, I am still here to tell the tale.

Fell Beck disappearing down Gaping Gill, without me, I’m glad to say

Most walkers are familiar with false summits — Ingleborough does not disappoint in this respect. What appears to be the top is in fact Little Ingleborough whose hump of a hill has to be climbed before the true summit appears. So this we did, then pushed on through the mist for another mile or so to the broad, stony plateau which is the top of the mountain. It was not, unfortunately, a day for the sort of views I described earlier, the hill being blanketed in cloud. We consoled ourselves with a flask of coffee in the shelter of the tall stone windbreak.

Andrew on Ingleborough’s summit.

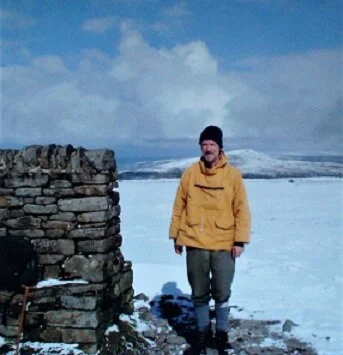

But there was another day, a few years later, I think, when the sky was blue and the fellsides a tawny brown. Standing at the top, taking in the view, I noticed to the north west a heavy, deep grey cloud approaching. Its advance was rapid and it swept over the hill depositing a load of snow as it did so, all in the space of about five minutes. The surrounding landscape was instantly transformed. When the skies had cleared, a man from Blackburn obliged by taking a photograph of me.

On Ingleborough, another day, Whernside in the background

Finding your way off the top of Ingleborough can be a bother in thick mist, but luckily I had a compass bearing I had made before pencilled on my map, so Andrew and I located the rocky path off the north edge and found the track across the boggy basin between the hill and Simon Fell and so began our return. We passed the ruins of an old hut, then negotiated our way through the extensive tract of limestone pavement before gaining the long, gentle descent into Clapham. Tired and damp we repaired to the inn for a welcome and necessary pint. As birthday presents go, I think that day, climbing Ingleborough with Andrew, was one of the best.

Until it all flooded back, after that little climb up Doon Hill, I had assumed that I probably would not go up Ingleborough again. Now, however, I am determined to do so, if my creaky joints allow, the next time I am down in Yorkshire.

And Doon Hill, by the way, is a place of much interest in its own right. It deserves a blog post of its own, so watch this space.