Dark Peak

For over forty years my home was Wakefield, a city on the southern edge of what used to be called the West Riding Conurbation, a great bruise on the map spreading from Halifax and Huddersfield in the west, through Bradford, where I was born, to Leeds, with all their industrial satellites in between. Wakefield was always a little detached and used to be the County Town of the old West Riding. One of the things I liked about the place was the ease with which you could escape from it. It stood on the intersection of motorways leading to all compass points and was mid-way between Edinburgh and London on the main railway line.

But for me, seeking the wide open spaces, the quickest and most tempting way out was to drive south-west in the direction of the Peak District. In less than an hour I could get to the country beyond Penistone and spend the day walking across the moors under huge skies, sometimes a crystalline blue, sometimes brooding and heavily rain-laden.

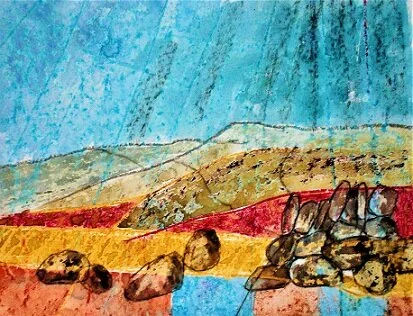

Pennine Sky

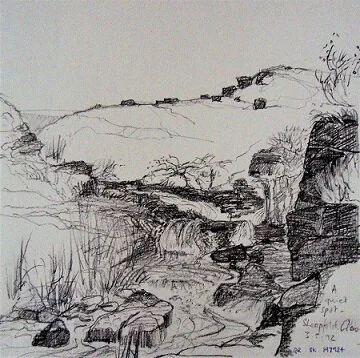

Here we are still in Yorkshire. Most of what is generally recognised as the Peak District lies to the south in Derbyshire. That is known as the White Peak, presumably because of the prevalence of the limestone witnessed in the silvery-grey of the scars and ridges of its hills and underground in the glimmering labyrinths of its cave system. But the part I visit is the Dark Peak. The underlying limestone is covered in a layer of mudstone and millstone grit. The resulting landscape is a moorland plateau of peat, heather and waving cottongrass, cut through with deep, stream-laced cloughs — Howden Clough, Gravy Clough, Hobson Moss Dike, Sheepfold Clough. Slivers of native woodland, oak and birch, grow along the banks of the tumbling ale-brown rills of these little valleys.

Sheepfold Clough

The upper ridges are characteristically punctuated with outcrops of gritty sandstone weathered into extraordinary formations, icons of the wear and tear of millennia of wind and wet, each with its own identity — Cakes of Bread, Salt Cellar, Hurkling Stones, Wheel Stones….

Derwent Edge

On more than one occasion I have been caught out in bad weather. I was once up on Howden Moor making my way by compass up from the valley to an outcrop of millstone grit known as Bull Stones. As I laboured through the thick heather, the darkening sky turned an inky black and an almighty downpour sluiced down. Mercifully my bearing was true — the Bull Stones loomed through the sheets of rain and I was able to shelter under the leeward side. Standing there, the rain dripping from my nose, I felt a huge contentment, not only because I was now in the dry but just at being there amidst the raw elements which in a strange way I perceived as companionable rather than hostile.

The other occasion was rather less comfortable but not in the end disastrous. I used to do a lot of fell-running and I had entered a race which led five or so miles across the moors and roughly the same distance back along Derwent Edge — a tough challenge at the best of times, but this was January and a bitter wind sharpened with sleet blew in from the east. We were on the return leg along the exposed gritstone edge when the sleet turned to hail. I felt as though I was being icily sandblasted, and for the only time in all my running my legs gave way through a combination of bitter cold and exhaustion. I veered drunkenly off the track and found myself stumbling through the freezing spikes of old heather. True to the spirit of fell-running, two other participants, completely unknown to me, stopped and helped me back on course and made sure I was fit to carry on before heading off again. I slowly regained my balance and jogged back to the finish. I completed the race the following year in clement weather.

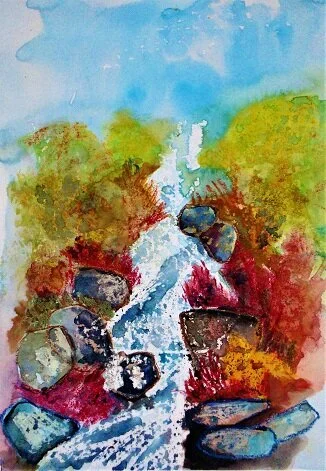

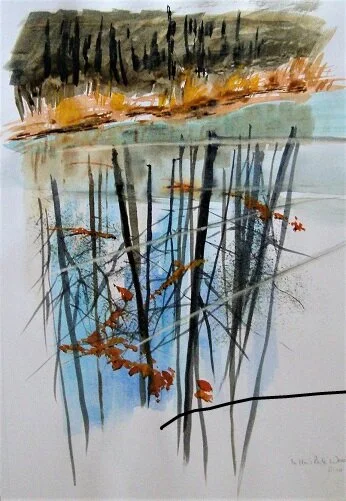

Here are two moorland studies:

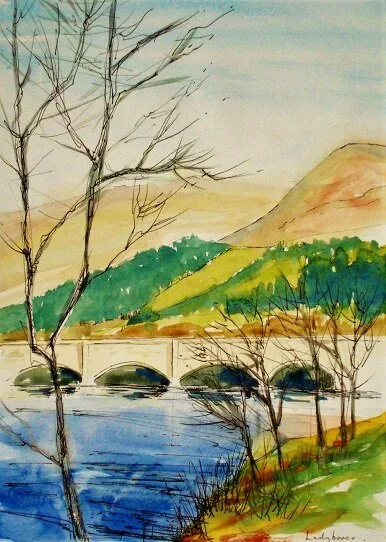

The Dark Peak is divided north to south by the upper reaches of the Derwent Valley. The river has from the early 20th Century been dammed in three places to form a chain of lake sized reservoirs: Howden, Derwent and Ladybower. Like scores of other reservoirs across the Pennines they were built to provide water for the thirsty masses of the towns and cities of Lancashire, Derbyshire and South Yorkshire. They are, just as is Thirlmere in the Lake District, now part of the landscape, beautiful and impressive in their own way, the hillsides sloping up from their waters clad in dark pine forest.

To stand beneath the Derwent Dam is an awesome experience.

It was here in the Second World War that 617 Squadron practised dropping the ‘bouncing bomb’ for their raids on the dams of the Ruhr Valley in 1943 in order to disable Germany’s industrial powerhouse. The film, ‘The Dam Busters’, includes footage of Derwent Reservoir with its castellated towers. To imagine this dam giving way is to shudder at the thought of the devastation wreaked by the breaching of the Mohne and Eder dams. Over 1500 were killed, most of whom were captive Soviet soldiers set to forced labour.

17th May 1943.The Eder Dam is breached (Bundersarchiv)

There was, in fact, a disastrous dam breach nearer home, only a few miles east of here, in Bradfield Dale, where a reservoir was constructed some fifty years before the Derwent series to serve the citizens of Sheffield. Dale Dike Reservoir had been completed in !863 and had just been filled for the first time when the dam gave way. The torrent of water surged through the villages downstream, through the Loxley Valley into Sheffield itself where it joined the River Don, the resultant flood ending up in Rotherham, fifteen miles from the original breach. Countless homes were destroyed and 244 people were killed.

The aftermath of the Dale Dike breach

During the building of Ladybower Reservoir the little villages of Derwent and Ashope had to be flooded, much to the protestation of the inhabitants. In periods of drought the remains of Derwent reappear, attracting crowds of visitors some of whom nick bits of masonry to prettify their back gardens. Others spray graffiti over the ruins.

Going, going…… Local inhabitants watch Derwent Church disappear below the water:

The Sheffield - Manchester road crossing Ladybower Reservoir

The moors of the Dark Peak are, like many upland regions, managed for grouse shooting. During the season, in late August and beyond, notices appear at the gates to paths and tracks warning you to stay off the moors. One day in early Autumn, the relevance of the season having failed to register, I set off on a little used track by a stream and worked my way up onto the moor top. I was suddenly startled by gunfire and thought I was being shot at. I crouched down behind a large boulder and peered out over the moor where puffs of gunsmoke filled the air. Then from another direction a line of men and boys with sticks and flags advanced, beating away at the heather, flushing the birds into the path of the guns. It was a fascinating, if unnerving, experience.

It amuses me to think of the current disgruntlement at the exemption of grouse shooters from the coronavirus restrictions imposed on the rest of us. It is a general resentment, I think, of the wealth and privilege of the landed classes and the types who enjoy blowing birds to bits as much as their freedom from these particular restraints. Another point of controversy related to this pastime is the burning of heather. Gamekeepers burn heather at the end of the season to encourage new shoots for the grouse to grow fat on for the next year’s shooting. Some farmers who have nothing to do with grouse shooting claim that the practice actually improves biodiversity — if heather is allowed to spread too much it crowds out many plant and animal species; apparently, curlew and golden plover flourish where the heather has been burnt. Old, woody heather is also more of a fire risk. Environmentalists, however, say that, quite apart from the animal cruelty aspect, heather burning ruins the peat layer, an essential storage for carbon, and releases unacceptable volumes of smoke into the air as well as increasing the flood risk. It does seem now that, despite the stalling tactics of some Tory ministers, George Eustace, for example, the Minister for the Environment ironically enough, more and more estates, especially those managed by such bodies as the National Trust and big Water Companies, are working to put an end to heather burning and even the practice of grouse shooting itself.

Moorland Stream

Here is a poem. I am making my way up a little stream above the reservoir at Langsett. There is smoke in the air. I trek up over the brow of the hill and see some way off a group of men at their task, burning the heather. It is a strange poem, a fiction, as most poems are, for at the time I am recollecting I was alone, even if the poem doesn’t seem to think so .

The Narrow Valley

It was the day the sky was blue as an egg

and we climbed the narrow valley towards that

smudge on the horizon…. a low cloud perhaps

or a trick of the air, something in my eye.

But we left the red pines and their intimate

scent and strangeness and followed the stream uphill,

ravelled it back to that blur on the moortop.

Sometimes as we went you were on the dark side

and I in the sunlight. Sometimes we would touch

fingertips across the trembling water, then

you’d flit off again, lost in the deep shadow,

while I kept my eye on the rim of the hill

and what was rising from it. So we wound up

the current to a seepage among wet roots

and you opened your hand to its moistening,

then led the way as we crested the gradient,

discovered the brilliant blue adrift with black.

Our breath caught in the acrid heat of the smoke.

Then I saw how you looked at them. Faces flushed,

they moved in an arc, their caps and leather coats,

with sticks and strident dogs, burning the heather.

And how your eyes flashed as it crackled and spat,

the fierce flame of it still blazoned on your cheek

as we came down the valley, out of the fire.

But the moors of the Dark Peak are now a landscape of the memory. Shall I ever go there again? Memory can work tricks…so often deceiving and a shifter of shapes. On this occasion, however, it has energised and inspired. I feel a need to visit those gritstone edges and great open skies once again.

The Path over the Moors