The Kreutzer Sonata

It was at a concert at a local arts centre some years ago that I first heard Janacek’s First String Quartet, called ‘The Kreutzer Sonata’. I was immediately gripped by its intensity and dramatic power. Before the performance the first violinist had told us how this music was Leos Janacek’s personal response to a story he had read about jealous love and its violent consequences. Why is it known as ‘The Kreutzer Sonata’ though?

Leos Janacek 1854-1928

In the first place, the ‘Kreutzer’ is the name of Beethoven’s Sonata No.9 in A major for violin and piano. He wrote it in 1802 for a young mulatto violinist, George Bridgetower, the son of a black page in the household of Prince Esterhazy, Beethoven’s patron at the time. He later revised the piece and, having fallen out with Bridgetower, dedicated it to the distinguished violinist, Rudolphe Kreutzer. It is the longest and most expansive in content of all Beethoven’s violin sonatas, a work of particular depth and invention. It is doubted that Kreutzer ever actually played it.

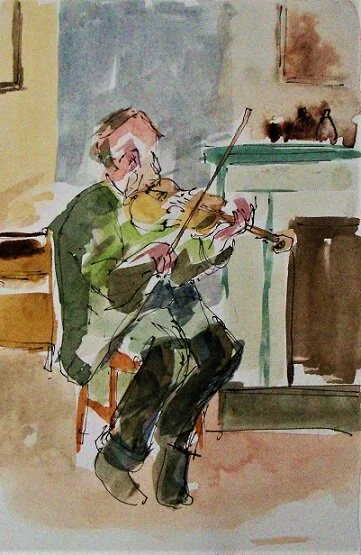

Beethoven and his ‘Kreutzer Sonata’

It was this work which provided Leo Tolstoy with the title for his novella, ‘The Kreutzer Sonata’, published in 1899. A man, Pozdnyshev, has a tempestuous relationship with his wife, by turns both passionate and violent. He rages against the dictates of conventional marriage — lifelong faithfulness, childbearing — and boasts about visiting prostitutes. His wife falls for a violinist and, in Pozdnyshev’s company, they play Beethoven’s ‘Kreutzer Sonata’ together. Pozdnyshev then deems music to be the greatest cause of adultery. One day he discovers his wife and the violinist together and in a fit of jealous rage stabs her to death. It is a sour tale, with its sardonic condemnation of sexual love and its misogynistic view of women.

Leo Tolstoy 1828-1910

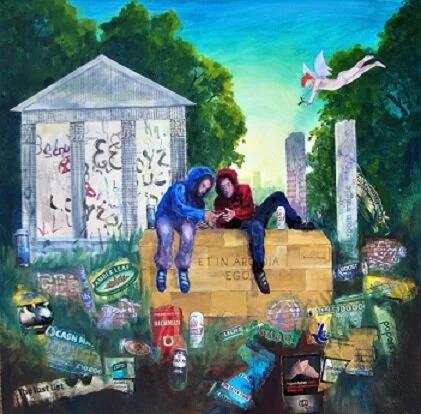

Rene Prinet’s painting of ‘The Kreutzer Sonata’ (1901)

The sort of conflicts and tensions between the sexes Tolstoy exposes so viscerally in the story are still with us today, in the present outcry against violence towards women in the street or home or workplace, and the harassment of young girls in school. Our protesters would not derive much comfort from Tolstoy’s terse dismissal of the dilemmas facing women in their relationships with men. Janacek’s reaction to Tolstoy’s story, however, was one of ‘burning sympathy for that poor, downtrodden female being.’ Whereas Tolstoy ridicules music as a corrupting influence and scorns the excesses of carnal love, for Janacek music and love are the most precious of human gifts. Of his quartet he wrote, ‘I had in mind a poor and tormented woman, one beaten and eventually destroyed, like the one described by the Russian writer, Tolstoy, in his work, ‘The Kreutzer Sonata’’. It is a work which, though just over a quarter of an hour long, packs a powerful punch and contains graphic musical themes depicting episodes in the story, the wife’s murder, for example. And, pertinently, in the quartet’s third movement Janacek writes a motif based on a theme from Beethoven.s sonata.

At the time of that concert I attended in the arts centre the news was dominated by shocking examples of crazed violence and bloodshed. One man had been stalking women on the city streets, killing them and dismembering their bodies. Another was running amok with a shotgun in the Lake District. It struck me how these events, however gruesome, became, aided of course by the febrile attentions of the media, dramatized, indeed fictionalised, until it was difficult to tell reality from soap opera. It was with these thoughts in mind that, shortly after the concert, I wrote a poem called, predictably enough, ‘The Kreutzer Sonata’.

The Kreutzer Sonata

You can, as you walk the red streets you work,

fall prey to a monster with a murderous eye,

to be captured, carved and cannibalised

and have what’s left of you dumped

in the murky swill of an industrial canal.

Or when you’re out shopping get in the way

of some crazed loner with a grudge

at loose with a shotgun,

have your life blown away at point-blank range,

end up as a chalkmarked shape on the pavement.

Both spectacular ways of going, with the promise

of blanket coverage, the televised grief of the nation

and shrines of film-wrapped flowers tied to the railings.

Alternatively you can,

as the first violinist will tell you,

be knifed by your insanely jealous husband

in the fourth movement of the Kreutzer Sonata.

It happens, we are told, on the viola.

After the vicious bow stabs on the strings

come the final tragic chords, dying away.

And then you’ll hear us clapping and whistling,

throwing our bouquets in the air

and crying for more, encore, encore.