River

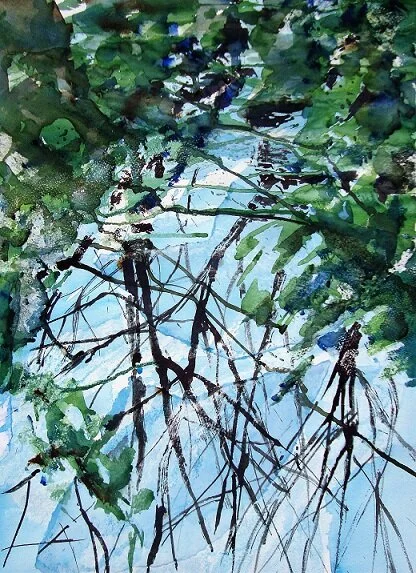

The boy leaves his bicycle on the verge and steps through the long grass to the river’s edge. The River Misbourne, hardly river — a good run-up and you could leap it. The boy kneels down and dips his hand in, the water limpid and cool, rippling over its gravelly bed, ruffling the green fronds of waterweed….the water spirits, their flowing tresses. The image rises and falls and sometimes vanishes altogether, like the stream itself disappearing into the beds of chalk beneath.

Here the Naiads swim…..

Over the hill in the next valley, another chalk stream, the Chess. The youth cycles along the narrow B road. A lively breeze, high white clouds, the river glittering alongside, circling the beds of watercress, alive, as he is in the bright air. A couple of miles further on and he is at the dig. They are excavating a Roman villa at Latimer, working away at the hypocaust, the underfloor heating system. The youth collects his trowel and brush, kneels down, this time in a shallow trench. Tenderly he scrapes the centuries away and sweeps them into a bucket. Tiles, ochre and red, where someone trod. Earthenware fragments, a fingerprint on the rim, and the river flowing by, the same river. But never the same river.

Never the same river……

*

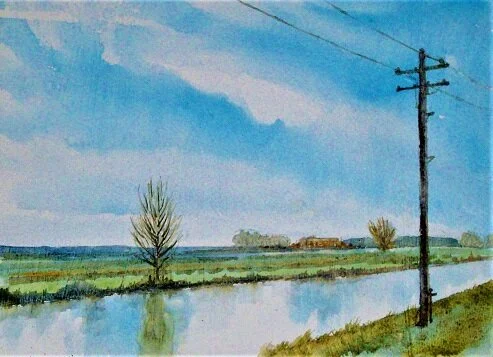

The River Witham has run out of running, constrained between man made banks as it slides placidly towards the Wash. Planes of earth — rich, dark fields — of sky, a sky scooping the youth up into its vastness, shedding its light back to the flat pale pane of the river. Little wooden footbridges over the dykes, his grandfather, staunchly upright on his big three-wheeler, a telegraph pole and a solitary tree the only other verticals…..grey fenland, wind, absence.

River Witham

*

The Calder is not a pretty river. After heavy rain the vegetation, twigs and low branches of its banks are strewn with an unhappy decoration of plastic bags, food wrappings, cans and bottles. But now the flickering reel of memory finds a man on a bike riding along an earthy path with the wide river to one side and a small lake on the other.

The river runs by…..

This stretch of the river is new.. It once flowed in a wide loop to the east but then the railway came. Rather than build two bridges to span the loop, they decided to straighten out the river. Beyond the railway embankment survives Half Moon Lake, the remnant of the loop, now a secluded, reedy haunt of anglers. These are the Washlands — the small lake, the half-hidden ponds and pools, the reedbeds, scrubby trees, almost-woodland, barely disguising the industry that once clanked and clattered beneath the surface.

Tunnel

Beneath the hefty thud of goods

he tunnels through

from ashfield to birdsong unravelling

among the osiers, grit crackling

beneath his bicycle tyres.

The air is edgy with echoes —

rattle of winding-gear,

diggers grunting

in the gravel beds, slush

of slurry down foot-wide pipes.

Resting on the bank

he watches the river’s heavy freight

slide by to spill at the weir.

Memory stirs and swells,

eddying among the reedbeds.

In his bones he hears the shouts

and laughter out of old shafts.

The hours pass like clouds

until he wakes,

the sand unsettling in his eyes.

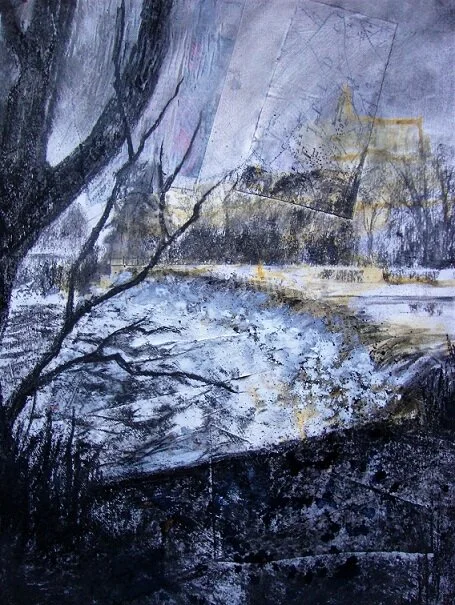

He rounds the end of the lake, becomes aware of a deep rumbling, almost subterranean. As the path tracks through the scrub, the willow and birch, the vibration becomes a roar. Through the rank vegetation he sees the gleam of the river smooth itself out, ready to make its plunge. He scrambles through. The weir.

Kirkthorpe Weir and its awesome five metre drop

The Weir

It begins with a rumour half-heard

through fallen leaves.

The river advances, its waters

collect and pool

unrolling a skein of dark silk.

Invites the conceit of stillness:

its surface pane

mirrors branches overhanging,

reflects to the last bolt

the white rails of the pier.

But underneath is the current’s sinew,

a stratum of pressure

building to the long seal-back

of the weir, held

only by the brim’s blade of light.

Until with a turbine roar the pent

power spills,

collapses down the tiered barrage,

exploding spume

in a backdraught of hissing spray.

Swirls then out of the mayhem,

veering and cutting

to escape in spent eddies,

slowing to swing

round the louring scarp of the landfill.

What’s left is a debris of floodweed,

sad foliage of

polythene, inlets of junk,

a shopping-trolley,

a traffic cone stranded in a tree.

And below the giant sluice-wheel

and mossed buttresses,

half-hidden in the undergrowth

two youths fishing,

perched on upturned plastic crates.

Deafened by the weir’s thunder,

passing a roll-up

across a cairn of empty cans,

they sit unspeaking,

wait all day for a twitch in the line

or, looking up, observe the heron

rise from its shallows,

wheel and track back up river,

flying direct,

low-slung, slow-beating time.

…..to another time. Incessant rain and half the town flooded. The great weight of water propelling the surge brutally downstream. On the path again but he cannot hear the weir, only the deep hiss of the onrushing current. He parts the undergrowth and steps out onto the high bank. The water is at his feet and the weir has disappeared. The river is so full it cannot fall, just sweeps on at its own height, brimming its banks as it stampedes round the next bend towards the landfill. The man is full too, of awe and fear. No dipping his hand in this river. This river is empowered, needs space…..

*

His finger traces the blue snake of the Calder, with its straitlaced companion, the Aire and Calder Canal, downstream to its meeting with the Aire a few miles away in Castleford. He is collecting confluences. This is what old men do. They pore over maps to work out where they are, where they’ve been and where they’re going. In this case, it is a patch of waste ground behind the high brick wall of a flour mill. He watches the sluggish brown waters mingle and gurgle onwards. Thirty miles east, the Aire meets between raised banks the breadth of the River Ouse, just beyond the village of Airmyn. He stands under a grey sky and watches the Aire muscle in on its big brother. Having logged the confluence to his satisfaction he returns along the bank and pops into the pub for some lunch. ‘Do you do food?’ ‘No,’ replies the wan barmaid. ‘There’s no call for it round here.’ He settles for a pint and a packet of crisps.

And about fifteen miles northwest, in a bleak and draughty field, the Ouse is joined by the Wharf, curiously narrow and subdued as it seems to look both ways before joining the flow as it heads towards the Humber.

The confluence of the Wharfe and the Ouse near Cawood

Can this be the same Wharfe that finds him on that walk in the Dales up Simon’s Seat with its craggy summit just upstream from Bolton Abbey? Park by Barden Bridge, stretch the legs along the riverbank, the Wharfe splashing over the limestone bedrock, to the stepping stones at Drebley, then veer off up the steep track to the hilltop. In Spring a small clump of snowdrops appears among the summit rocks. The work of nature, or, as he prefers to imagine, faithfully carried up here once to commemorate a beloved husband….or dog? Standing there tracing the river’s course below — Appletreewick, Burnsall, Grassington, and, beyond, Great Whernside and Buckden Pike. Then down the broad back of Barden Fell — two buzzards circling, grouse gobbling — back to the river, down through the Valley of Desolation. Dicken Dike with its little waterfall, and Sheepshaw Beck join hands to tumble down Posforth Gill. Here, in 1826, a violent storm ripped up trees and hurled a cliff down the valley. Nature has mended the wounds and the valley is desolate no more and is graced by a fine waterfall, its waters rushing to join the Wharfe below. As is the wandering man…back along the high track through the woods, looking down at the Strid, where the whole volume of the river tears through a rocky gap the width of a reckless leap, and returning to where he began. He thinks of that draughty field near Cawood.

River, a memory…..

*

‘The child is father of the man’, and this man is once again in a chalky valley, two hundred miles north of his boyhood, in the Yorkshire Wolds. It is May and the sun blazes down. It is worth celebrating.

May Hosanna

May has pitched an armful of Spring snow

at the shouting wind. It has settled

and taken root in the flint

where hawthorn crowds and jostles on the steep chalk.

In the dry cobalt of noon

angels of gorse

those concentrations of hectic air

flame out their liturgies of gold.

Only a crown of trees on the hill’s shoulder

guards an almost liquid cool

where deep shadows are draughts of silence

against the burning loud hosanna in Millington Pasture.

Among these flinty ridges water is precious. Here the wellsprings are railed off and signed: ‘Millington No.1 Spring’, ‘Millington No.2 Spring’, and there is a third downstream.

Springs of clearest water well

from hidden places. Deep inside,

it trickles and connects, rising

to murmur from this dank enclosure.

Oozing out it darkens grass,

inviting silt where it swells

down the hint of a gradient.

Cattle stand by a simple footbridge

where a man looks down,

his face caught out against blue sky.

Glancing up he sees the hawthorn hill,

the trees, the inert wold.

The wind has dropped

and surfaces assert cool atoms.

The hosanna’s dumb.

Leaving his reflection sliding on

he closes his map and turns away.

Still waters

*

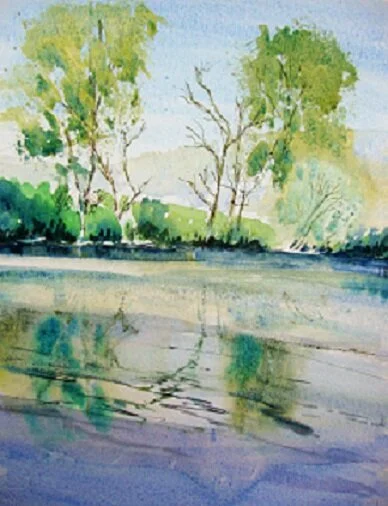

The Tyne, our Tyne, springs in the Moorfoot Hills and works its thirty mile way through gentle Lothian countryside to slink through its wide estuary to meet the Firth at Belhaven Bay.

A little sidestream of the Tyne

Another Spring, and the riverside trees with a tangy dusting of lime green. My former selves through their various confluences have ended up here, in me….another wellspring, lost in my thoughts again, the river a perfect companion — andante moderato, no rush. Here is the ford, and the footbridge where I stand for a moment sensing the arrival of Spring, nature’s sap rising as the stream rises somewhere in a damp patch of moorland. What did A.A.Milne say?

‘Sometimes, if you stand on the bottom rail of a bridge and lean over to watch the river slipping slowly away beneath you, you will suddenly know all there is to be known.’

There has been rain and the river is silty in its slow drift. Then I see it….a bit of branch, a bunch of floating weed? No, it is too steady, too direct, nosing down the centre of the current. Then the glossy domed head, the little dark eyes. My first otter. It is only a glimpse. Perhaps it smells me, for it melts below the surface and becomes the current itself. It is at one with the watercourse, and here am I chafing at the unsporting brevity of the sighting, trying to grasp a world which always runs away from me.

Too long in a dry valley

__ the whin grizzled and mealy,

stones bare of lichen —

I came to the stream.

I watched the water’s rapid muscle

flex and spend,

heard the humming current

swallow and break.

Each ripple was the truth

we can never hold,

each shadow slipping under the liquid skin

the calm repose we hope for

endlessly.

‘Rivers know this: there is no hurry. We shall get there some day.’

Winnie-the-Pooh