The Lakes

This time last month I was in the Lake District for a few days walking. The first snow of the season lay on the high fells, brilliant in the bright sunshine. It was beautiful, an enrichment for both body and mind. But as I write this the Lake District is as good as closed. One of the ironies of the present situation is that, when the pandemic officially became a ‘crisis’, people headed for the great outdoors to ‘isolate’ themselves only to find everyone else doing the same.

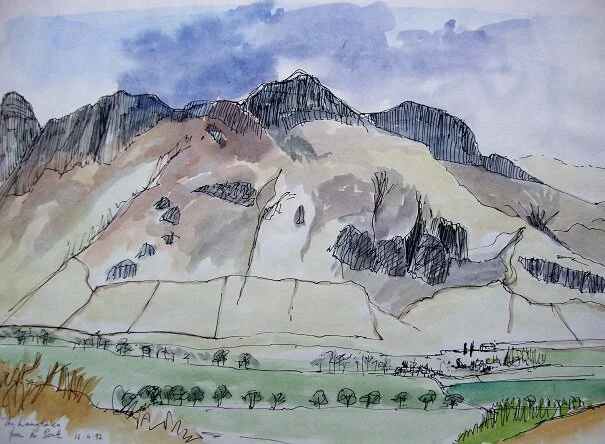

I’ve been visiting the Lakes for the past fifty-odd years. An old sketchbook throws up a couple of scenes.

A pen and wash sketch of the Langdales, when I was camping in the valley below.

Looking north from Fairfield in winter. A charcoal sketch

But as for my first twenty years, it was with the mountains as it was for the sea. They were a distant dream. My stamping grounds as a boy were the beechwoods and chalky hill ridges of the Chilterns, beautiful but domestic, their climbs often steep but brief. It was only in my early twenties when I left the warm south that I discovered the great, airy landscapes of the north — the wide limestone reaches of the Yorkshire Dales, the gruff gritstone edges of the Pennines and, just two and a half hours away given a clear run up the A65 in my Morris Minor, the stunning grandeur of the Lakes.

There had been, however, tantalising glimpses of what lay beyond my home horizons. When I was twelve my mother put me on a train at St. Pancras bound for Scotland to visit various aunts, great-aunts, second cousins and other assorted relatives on her side of the family. She sat me opposite a stout lady whom she asked to make sure I had a good dinner and got off at Kilmarnock, probably in that order of priority. I would have preferred to be left to my own devices. Luckily the stout lady did not feel inclined to make conversation, preferring to read her ‘Woman’s Own’. She did, however, drag me off to the dining car where I pecked away at some sort of grey meat swimming in a pool of peas and thin gravy.

It must have been late afternoon when we steamed up through what I now know to be the Pennines. It was somewhere beyond Ribblehead, I suppose, that I looked westwards out of the rain-spattered window. I still see in my mind’s eye the overarching, lowering sky, ochre, shower-swept, and far away the hazy contours of a range of hills, impossibly distant. I stared at the fleeting scene in wonder. It was, I think, my first sight of the Lake District.

A second such glimpse occurred when I was in Scotland, but not before a number of experiences which have lodged themselves in my memory. At my great-aunt’s in Kilmarnock I had to endure my second unpalatable meal of the day. She set the dinner plate before me. ‘Here,’ she said, ‘a nice bit of tongue.’ Whichever unfortunate beast the tongue had belonged to I do not know but I found it completely inedible. My great-aunt removed it sniffily. Something from my stay with her did stir me though, in the same way as that view from the train window had. Well, perhaps, not in quite the same way….

It was a modest house where most activities went on in the kitchen. I was sitting in the corner reading a book when a young woman came in wrapped in a towel. She must have been an aunt of some sort and her name was Janet. She put the towel to one side and proceeded to wash her hair over the large porcelain sink. She wore only knickers and a bra. I had never seen a woman in such a state of undress before. I was, though, less interested in the knickers than her bra, and the way her slender arm rose up from it to massage her scalp. If I’d known then what the word ‘erotic’ meant, it would have sprung to mind at that moment.

I then stayed with further distant relatives in Glasgow. They lived in a tenement block and I had to share a bed with a young man. I had no idea who he was but I do recall that the bed sprang up on hinges into a cavity in the living-room wall — once you had got up, I hasten to add.

The last port of call on my Scottish travels was with an Aunt Irene, who lived in Perthshire. She lived on her own in a bungalow, kept chickens and had a little black dog. I got on well with her. She was a vet and I accompanied her on her rural rounds. I assisted her in the process of debeaking turkeys. This was to stop them pecking each other. You held the bird under your arm and wedged your first finger between its mandibles then shoved the upper one into the debeaker, a sort of electrified guillotine.

Me holding a turkey, and the debeaking machine.

One day Aunt Irene took me to Loch Tay for a picnic. We sat on the lower slopes of Ben Lawers. When we had finished our sandwiches she said I could go off and explore. She lay down in the heather and had a nap. I bounded up the track, followed by the dog, eager to see what lay ahead. The landscape to me seemed vast, the huge flanks of the mountain sloping down to the glittering loch below. Sometimes my mind tries to convince me that I reached the top but I think that is but an embellishment of the memory. At any rate I did arrive at some sort of prominence and stood there gaping at the breathtaking vista laid out to the north, range upon range of hills receding into a bluish distance like waves. The Highlands.

When I got home I went to the local library where they had a complete set of cloth-bound 1” Ordnance Survey maps. I fished out those for the north of Scotland and laid them out on the big tables. Here were whole maps showing just continuous whorls of light brown contour lines and the thin blue meanders of streams, with hardly a dwelling or track in evidence. I turned these acres of wild emptiness into my own fantasy landscape which I roamed intrepidly, a little black dog at my heels.

*

I came back north to study and work, and so began a regular exploration of the peaks, valleys and lakes of the Lake District which continues to this day. Memories float up like smoke from a camp fire….

— with my friend from college, Richard, on the shore of Ullswater, our A-pole tent pitched in a farmer’s field and the flames crackling between us as we toast our hands, drink cans of Younger’s Tartan and smoke….

— with a fellow teacher, Gerard, and his dog, a few days before Christmas, camping at Great Langdale, climbing Wetherlam and the Coniston ridge, our crampons biting into the crystalline snow….

— with Will and a group of boys camping at Gatesgarth at the southern end of Buttermere in the shadow of Fleetwith Pike and taking them round High Crag, High Stile and Red Pike, with hot chocolate in the café in the village….

— and then with Dave, again with a party of boys, at Wasdale Head. Dave is a rugby coach. I, knowing nothing about that strange game, am left to ‘do’ cross-country. The group is a mixture of his herd of stocky young players, vocal and communal, and my assortment of stringy introverts who prefer running with a peculiar singleness of mind through muddy fields to heaving away in a scrum, arms round each others’ buttocks. They get on surprisingly well though.

We have climbed Scafell Pike by the Corridor Route, crossed by Mickledore to Scafell. On the way back down to the campsite, a boy named Fuzzy Parsons, a young rugby player as broad as he is tall with a cloud of frizzy blond hair decides to hurl himself down the steep grass slopes in ever more reckless somersaults, to the cheering, jeering delight of all. He is impervious to injury. Health and Safety has not yet raised its admonitory hand.

On the last day they are given a choice: to amuse themselves around the camp with Dave or do a final walk with me. I am therefore left with a tiny band of stalwarts and lead them up Great Gable and Kirk Fell. Or. to be more accurate, am led by one of my young runners, a wiry, bespectacled youth, a bright scholarship lad named Eric after his grandfather, a miner. He is always skipping ahead and has to wait impatiently for the rest of us to catch up. I hear his piping voice now. “Cum on, sir! What’s keepin’ yer?”

*

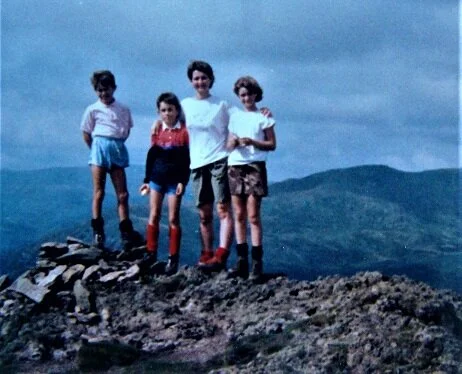

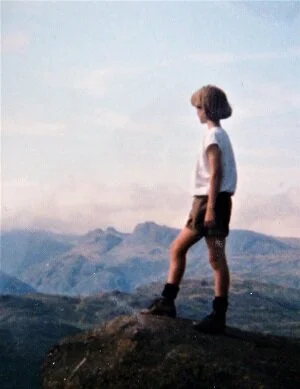

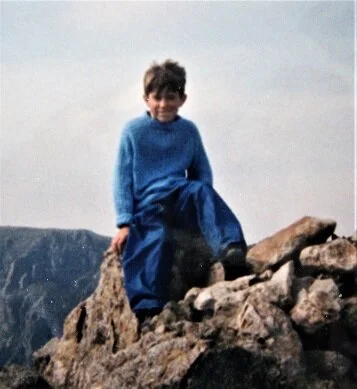

When my own children were old enough we took them to the Lakes. For their first trip we camped at Low Wray at the northern tip of Windermere. They wore in their hiking boots on Loughrigg Fell, Wansfell and Harrison Stickle in the Langdales. A few pictures from the album:

On Wansfell

Kate, looking towards the Langdales

James on Harrison Stickle

Later, when they had grown up, I went with each of them on occasion to the Lakes. James and I stayed in a B&B in Ambleside run by a couple from Yorkshire. The husband went out into the fields every morning to collect mushrooms which he would cook for our breakfast. I stayed in Keswick with Kate. We took the boat across Derwent Water and walked the ridge, over Maiden Moor and High Spy and so down into Borrowdale.

Kate, descending the rocks near High Spy

And with Andrew I did Fairfield, the Horseshoe, a strenuous walk but wonderful, from Ambleside along to Rydal, then the long climb up Heron Pike and the smooth dome of Great Rigg to the rather formless summit. We returned by Hart Crag, then High and Low Crag, like walking on air. I am tempted to say that the best thing about the walk is the end. The final mile down the track from Nook End emerges onto the Kirkstone Road directly opposite the Golden Rule, where you can collapse by the log fire with a beautiful glass of Hartley’s XB at hand!

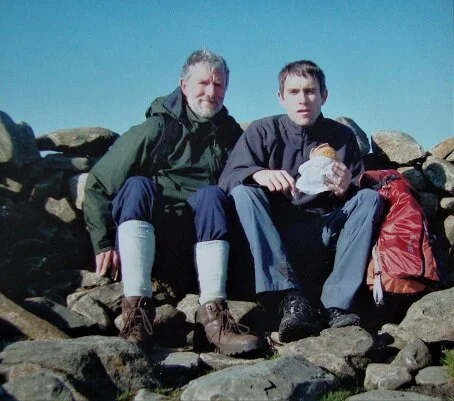

Me and Andy on top of Fairfield

It was on another occasion that I walked the Horseshoe in springtime snow. I later wrote a poem about it.

Fairfield Horseshoe

Indifferent beast

clad in this pelt of April snow.

Nothing moves you

despite the wind’s remonstrance

and the fretful watercourses.

Skies threaten and come to nothing.

The raven’s rasp falls on deaf air.

In this white sorcery

I cannot scratch your surface

but I begin to take you in.

I track your horizons, let

my eye chase the rig’s contour.

I log your cairns,

read the runes of your rockface.

My mind’s glacier discovers

the deep scope of your fellside.

I penetrate the mist that settles

round your summit’s dubious logic

until I find clouds opening,

shedding light.

Coming down, my bearings sound

your dark proclivities

and at my cry I fancy

something echoes back.

Although I leave you cold

you’ll still be with me

when my footprints melt.

I’ve done your Horseshoe,

that rough, contrary U,

and nailed it to my memory’s barn door.

Great Rigg