Getting On

Old people rarely regard themselves as old. It’s always the others — the old woman clogging up the supermarket aisle hovering over the tinned soup, the white-haired ancient spending an age at the cashpoint (what on earth is he doing ?!), the elderly driver in front hogging the middle of the road, peering through the steering wheel as he noses along at twenty mph.

To Be Like That

To be like that, I gasp, appalled —

taking all morning to dodder to the newsagents

for your Old Holborn and the Mirror,

then back to your solitary airless room

clutching the wall as you emerge from the subway

to catch your breath, blind

to the insolent graffiti your fingers dither on

delving for your pass as you mount the bus,

then grasping at air as you lurch to your seat,

or at the checkout excavating your purse for coins

to pay for that small tin of soup and a jar of potted meat.

To be like that, I think, aghast —

sitting all day in a high-backed chair

dribbling down your bib,

the TV’s lurid clamour unheeded

having to be carried to bed or (God forbid!)

hoisted up in straps like some mute ailing beast,

finally tucked in, dosed up and fed with a plastic spoon

until at last, your life shrunk

to four walls of institutional cream,

you don’t know where you are or who,

watching indifferent hands wiping your skin.

To be like that, I shudder —

as I go up to bed and pause,

sensing the stairs grow steeper,

hearing a snigger behind me as I take the top step

too briskly and grope for the handrail,

feeling my heart miss a beat at the twist of a stab in the back.

A rather ungenerous poem, I suppose, about the decrepitude that can accompany old age, but such a recoiling merely reflects the dread of ‘being like that’ and the reluctant admission that I am not far behind. Nevertheless, though in my eighth decade, I still cannot accept that terms like ‘old’, ‘aged’, ‘elderly, let alone ‘geriatric’ or ‘senile’, apply to me. I might grudgingly admit, however, that I am ‘getting on’. They say you are as old as you feel. Certainly, much has to do with the state of your body and mind. I have had the good fortune never to been seriously ill and mentally I still often feel like an adolescent, sometimes shamefully so. My time will come, of course. In my teaching days I had a colleague who was the picture of ruddy complexioned good health. He was a practical men, immensely knowledgeable about the properties of wood, metal and moving parts, a keen motorcyclist, walker and Scottish dancer. One day, out for a walk with his family he simply fell down dead.

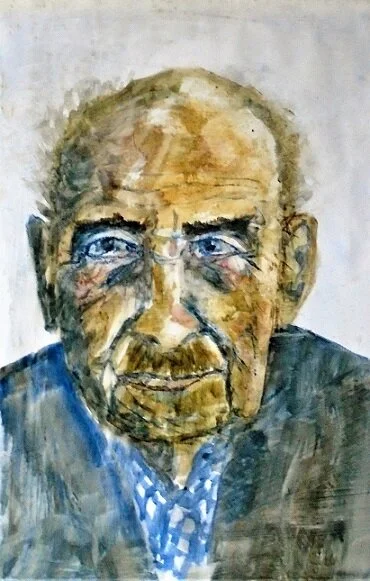

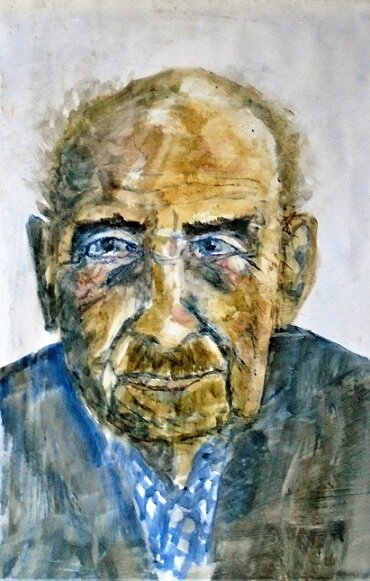

Old man

I once lived next door to an old man — let us call him Len — who had retired many years before from the mines. I rarely saw him and when I did it was for a brief exchange about the weather or his privet hedge, his cigarette dangling from his nether lip. His car stood outside but he never drove it. I built up a picture of Len, therefore, from the sounds I heard through the of the walls of our tightly packed terrace houses. I mused on the realisation that my bed was but two bricks away from his bathroom.

Neighbour

I knew him by the emphysemic cough I woke to,

the rattle of his piss ten inches from my pillow

and then the furious sluicing as he yanked the chain.

I monitored his palsy by the tap tap of his spanner

searching under the sink for a nut to tighten,

indulged the martial music marching through the wall

of the black-and-white war films he turned up too loud.

I picked up noises echoing back the decades: the thin squeak

of the pulley-wheel his old clothes-airer hung from,

the rummage in his hearth as he raked the complimentary coal

that burned through the bricks of my chimney-breast too.

Fifty years hewing the black rock had turned him troglodytic.

He still blinked at the light as he carted his ash-pan to the bin

or shuffled out to turn the engine of the car he never drove

but just warmed up, though weeds grew round its wheels.

I never crossed his threshold but once took round

a misdirected Christmas card and glimpsed a ceiling brown

with nicotine, reeled at the reek of his Capstan Full Strength.

That was the last I saw of him and what I heard

slowed down or stopped: the roster of clicks, thuds and scrapings

he’d no idea got through to me. Only the cough got louder.

It was the Winter did for him – it took him out

without a sound. Now when I dust my mantelpiece

all I can feel is a house losing its heat,

all I can hear, the slow drip drip of empty shafts.

Another old man

A few words about the nature of poetry — my poetry, anyway. Poets are accomplished thieves and liars. Thieves not just because we burgle the language of other poets — we all have our influencers — but also because, like jackdaws, we seize the bright baubles of what the world has to offer, including other people and their experiences and turn them to our own use. And liars because we distort the facts to fall in with the story we want to tell. Sometimes, the writing of the poem itself unearths an idea that was hidden before and so veers off in a new direction. It is a mistake to rely on a poem for facts — though I would make a distinction between fact and truth.

Old woman

This last poem, for instance. I risk disappointing you when I tell you that it is not what it seems. It is certainly rooted in real experiences but the elderly lady the poem appears to be addressed to is actually an amalgam of two — or possibly three — aged relatives of one sort or another (one, indeed, is still alive) Somehow, their stories fused into one and the poem is the result. Perhaps it would be better not to admit this, but so be it. It would be interesting to ask yourself if this knowledge changes your reaction to the poem.

In Memory

At last your mind went dandelion-clock,

each day another blow

to send figments of your past careening

to some lodgement in a tangled undergrowth.

Naked as a peeled sapling

you pirouetted round the TV room,

old men watching with dribbling eyes.

Or, pursued by nurses through the shrubbery,

you darted between the azaleas twittering

like a goldfinch cast into the buoyant air.

Then, when I had to come (trying to fly

you’d fallen from the terrace, your twig leg snapped)

you burrowed beneath the pillows, back

to some hill-station in Malaya

shouting down a telephone,

Have the men got through!

I propped you up, pressed a finger to your lips.

They made it Aunt, they’re all OK. Now here’s your tea.

I’ve tried to match you with that wry and artful

Miss we’d visit on Saturdays —

cakes, Snakes and Ladders, when always

you’d let us almost win then throw your wicked dice.

In summer you’d drive us to the beechwoods

in the Austin Seven,

intrepid, all talk forbidden,

your gloved hands gripping the wheel.

Then on the tartan rug it was

barley-sugar sticks and cherryade

before you quizzed us

on Capital Cities and Flags of the Commonwealth.

Suddenly tired you’d send us off to play

but I’d look back and see you

beneath a tree in a shaft of light

smoking your Craven A’s, and think

of that other life you never

talked about – catching the train each day

to somewhere down the Metropolitan Line.

You only told us that it ended in HQ.

Now that the final phonecall’s come

I’m standing by your bed,

you in your nightdress wide-eyed, paper-thin,

grafted to dripping tubes, —

tendrilled to a screen your thin green pulse threads through.

Your fingers are fluttering on the sheet.

I cup them in my hands and feel

the light dry touch of moth-wings wanting to be free.

The clock’s tick tells me it’s time to leave.

I’m letting you go.

Retreating down the corridor, uncertain

if I hear your voice, its fragile glass,

calling goodbye, goodbye, goodbye,

I’m wondering if I knew you, ever, anyway.