Harbour

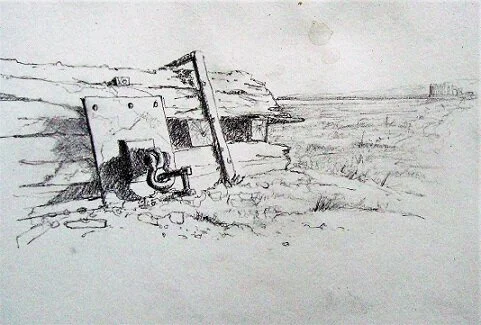

I was walking along the shore — seawrack, shoals of pebbles, the rotting, rusting remains of an old wharf, one great mooring ring still intact. A rather bleak stretch of coast between Barns Ness Lighthouse and the looming concrete cube of the nuclear power station at Skateraw.

The old, collapsed wharf and the power station in the distance

As I skirted the edge of the low dunes, there among the sea debris was a dead herring gull…..

…..coming across this makeshift

crucifixion of bleached bone and feather,

its wrecked fuselage and wrangled wings

and the yawning mandibles unhinged,

I wonder what battering

wind or water wall broke its final back,

sucked its flight askew like a comic umbrella.

I try to fathom the mashing

of its marble resistance, the unscrewing

of that eye’s hard purpose,

with the quiet tide now lapping

its feet, rinsing the ochre stains,

and a low wind echoing the cry of gulls.

*

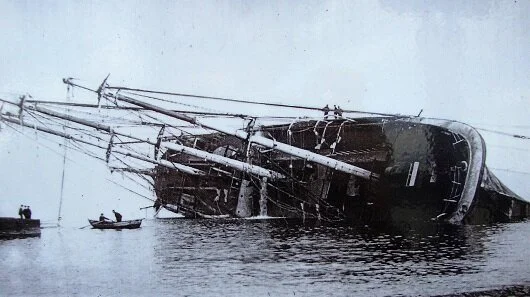

The sea can be merciless. In the days of sail many ships were wrecked along the coast hereabouts.

Dunbar born John Muir, the renowned naturalist and pioneer conservationist, recalls his boyhood:

‘Many a brave ship foundered or was tossed and smashed on the rocky shore. When a wreck occurred within a mile or two of the town, we often managed by running fast to reach it and pick up some of the spoils. I remember visiting the battered fragments of an unfortunate brig that had been loaded with apples, and finding fine, unpitiful sport in rushing into the spent waves and picking up the red-cheeked fruit from the frothy, seething foam.’

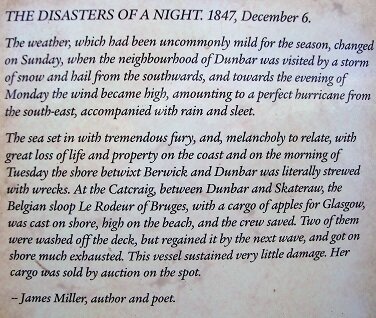

This is how the wreck was reported locally:

John Muir was nine years old at the time

*

When I listen to the Shipping Forecast in the morning and hear warnings of gales in Cromarty, Forth and Tyne, I think of the little vessels out in the North Sea lurching and swaying in the deep waves, longing for a haven to return to. I look out of my third-floor window and see the town tumbling gently down to the sea and the protruding east wall of the old harbour. This was not the original harbour, though. In the Middle Ages it was a mile or so along the coast at Belhaven, where the Biel Water flows into the bay. Now there is only a narrow channel, sand, mud, dunes and salt-marsh, and Belhaven is better known for its brewery, one of the oldest in Scotland.

It was in the 16th Century that the harbour was relocated to the town. The Broadhaven was simply a refuge in an inlet between stacks of basalt rocks — Dunbar is built on the site of an ancient volcano. Later, the Broadhaven was extended and a wall built, and later still it acquired the name, Cromwell Harbour. A year after beheading Charles I, Oliver Cromwell headed north to confront the Scots, with whom he had both constitutional and religious differences, and won a decisive victory at Dunbar in 1650. He welcomed the gain of the harbour to strengthen his power at sea and contributed £300 to its renovation and extension.

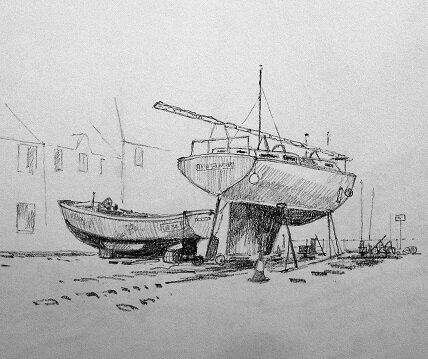

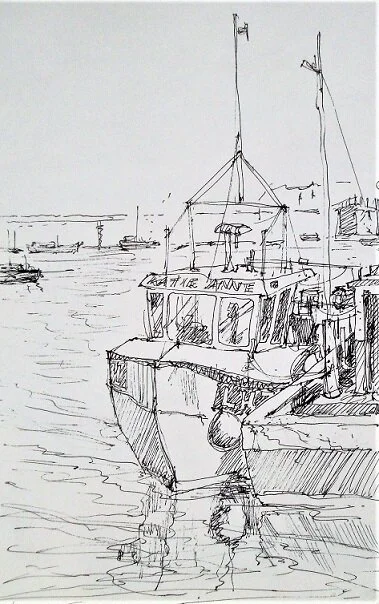

This harbour is one of my favourite spots to sit around and sketch. What better exercise for the pen or pencil than to draw the boats, the stacks of creels, coils of rope and all the paraphernalia of the quay.

An interesting feature is the Mariners’ Monument. An impressive structure and with its neo-classical lines looking oddly out of place on the cobbles of the old harbour, it was erected in 1856 to commemorate ‘the fishermen of Dunbar to whose perilous industry the burgh owes so much of its prosperity.’ Embedded in the stone frontage is a large barometer for the use of the said fishermen. A little plaque bears the words:

O weel may the boatie row

That wins the bairnie’s bread.

Here are some more sketches of Cromwell Harbour:

*

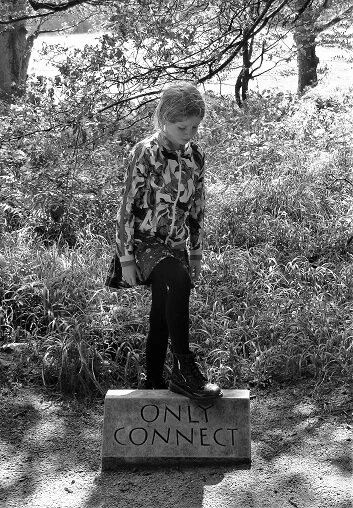

The fishermen work on their boats, repairing, repainting, or sit on upturned crates mending their nets. The image of mending the nets in harbour is a potent one for me. I sometimes think of human society as a big net bound by a web of connections, which, however, is always fraying, loosening, breaking. It is said that human beings are social animals, and that is true, bound as we are by tribe, blood, creed and language. But there is a sense in which each of us remains a solitary individual seeing the world through his or her own prism of genetics and unique experience, always on the lookout for points of contact, ways to relate. The epigraph of E.M.Forster’s ‘Howard’s End’ is ‘only connect’. It is a motto for human relationship and love. ‘Only connect the prose and the passion, and both will be exalted, and human love will be seen at its height. Live in fragments no longer….’

It seems our constant work is to keep on mending nets.

An old fisherman sits by the harbour wall mending nets.

He ties the loose ends and sews the torn mesh.

Gulls flock and clamour, white flecks

weaving and fraying in the wind.

You, my daughter, are looking out to sea

with mist in your eyes. Your children on the rocks

probe with a stick the little pools of sky.

Tonight the stars will bloom into their constellations.

*

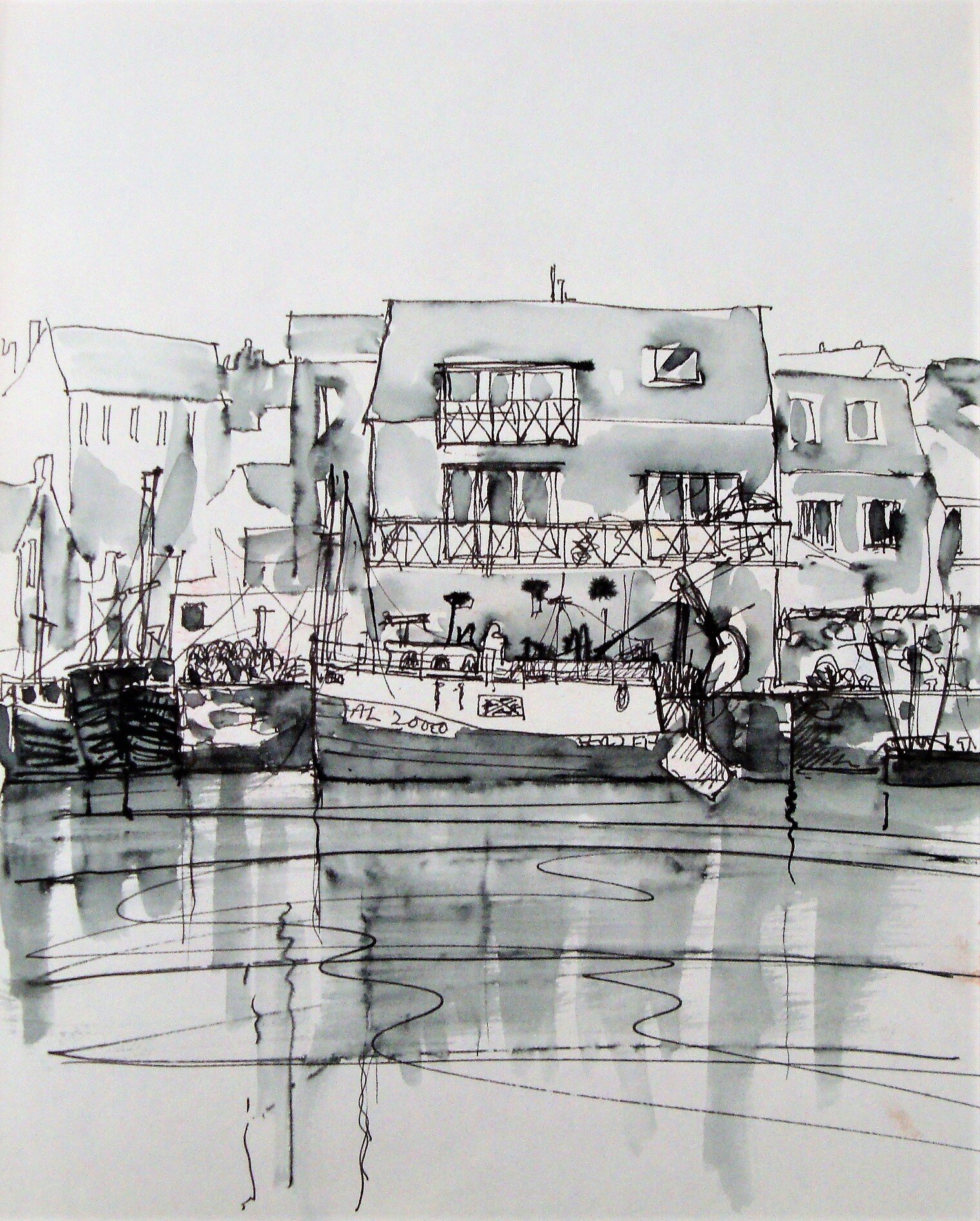

What you see when you arrive at Dunbar Harbour is not Cromwell Harbour at all — that is tucked away round the corner — but the Victoria Harbour and the remains of the castle on the seaward side.

Victoria Harbour, a painting in acrylic

The new harbour was built in the early 1840’s to cater for the burgeoning of the North Sea herring fishing. To make an opening to the sea the services of a young engineer, Robert Thompson, were employed. He had invented an electrical device for setting off explosives. The rocky barrier was blasted apart, unfortunately bringing down further sections of the already sorely ruined castle. The herring fishing has long died away but a faithful collection of little boats still comes in with its hauls of lobsters and crabs. A large, detached propeller stands on the quay in memory of a local man, Robert Wilson (1803 - 82), who as a young boy was fascinated by paddlewheels and windmills and went on to invent the ship’s propeller.

Robert Wilson’s propeller, and a couple of sketches of Victoria Harbour:

*

The castle had been a ruin for three centuries when John Muir was a boy and was a heady temptation for the young lad and his friends. ‘We tried to see who could climb highest on the crumbling peaks and crags and took chances that no cautious mountaineer would try. That I did not fall and finish my rock-scrambling in these adventurous boyhood days seems now a reasonable wonder.’ No Health and Safety in those days. The castle is now fenced off, of course. It is home only to great summer flocks of kittiwakes, perched on the ledges of their tower-block, wheeling out over the harbour with their squawking cries.

Another painting of Vitoria Harbour

*

A swing bridge over the channel between the two harbours leads onto Lamer Island, now an island no more but still the northern point of the area, a protrusion of basaltic rock. On this outcrop was built a fortification, the Battery, in 1781 to resist the advances of American privateers and their French allies during the War of Independence. It is said the guns were never fired in anger. In later times the structure served as a hospital for infectious diseases, which has a certain resonance today, and then a military hospital for unfortunates wounded in the First World War.

Now, however, it has been imaginatively recreated as a place for leisure and the performing arts. There is a set of stainless steel ‘sea-cubes’ etched with depictions of North Sea micro-organisms. There are gravelly beds where thrift and other sea-flora grow. The centrepiece is a small amphitheatre with tiered wooden seating, which, to my great happiness, is labelled with the sea-areas of the Shipping Forecast! So I can sit with my legs dangling over Forth and Tyne and think of gale warnings.

I can look out to sea over the red sandstone battlements — the encircling rim of volcanic rock, the massive boulders which now block up the entrance of the old Broadhaven, the little rocky islands with their gangs of cormorants. And I can read artfully placed plaques inscribed with whimsical fragments of local folklore. One reads,

‘Boys come from the Bass Rock, and girls from the Isle of May’.

And it is from this spot that one day I peered over and watched these boys, with something of John Muir’s spirit, impress their girls by jumping off the harbour wall into the waters below.

DANGER ‘No Diving’

The boys are leaping off the harbour wall,

shivering in their cold, blue skin.

Their girls huddle in thin coats and smoke.

Kittiwakes jeer from the castle ruins.

Gulls whine overhead. The law

is out of reach or lolls in the shadows

looking the other way.

They catch their breath, stiffen their sinews,

then take their fledgling plunge, taste

the fatal sweetness of blind risk.

Bony boys leaping, falling angels,

off the edge of the world.

Into the harbour…..