Memories of Trees

‘forever hoping I can find memories, those memories I left behind’ Enya

*

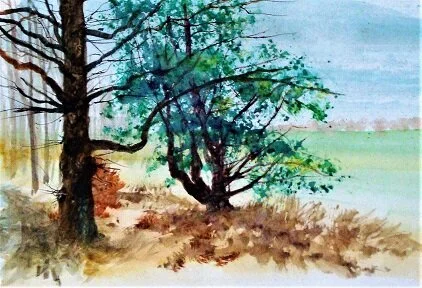

There is a spinney, a narrow stand of trees edging the drive up to the Big House, the farm. It is inky dark. A full moon hangs in the treetops like a silver bauble. It is smiling. In the luminous grass below, among the flitting, glittering insects of the night, sits a small boy. His pale face is round like the moon. He is not smiling, but neither does he look particularly unhappy.

*

Behind the farm cottage is our holly cave. In the centre is the tough, erect trunk and from the crown tumbles a dome of dark, waxy leaves. This is where we go and play, my sisters and me and the boy and girl from the Big House. We make seats and tables out of logs and straw bales. In here we cannot be found. I am standing by the trunk, pointing to an imaginary blackboard. I am the teacher.

*

When I go to school I pass the holly cave and take the path along the field edge. I’m on my own. My sisters are not old enough, and the boy and girl from the Big House go to a different school. Always I have this dread in my throat, for I do not know whether the brothers will be lying in wait. Two of them, with the same scraggy black hair, sitting on their red bikes, where the path comes out onto the ridge road. Sometimes they fling twigs at me and other bits of vegetation, sometimes lumps of language which I don’t understand. They snarl and make as if to come for me, then laugh and ride off. They have never yet laid a hand on me.

*

Winter now in the tall schoolroom. The windows are too high up to see out of. A huge black stove knocks and hisses in the corner, and the crate of frozen milk is thawing out, the silver bottle-tops thrust up on pillars of ice. The teacher is a fat woman and the children make rude jokes about her, but she is always kind to me. Today she is reading a story. We sit before her, cross-legged on the bare floorboards. She finishes a page and holds the book up for us to see the picture. A night time picture of trees and a big round moon in the branches. Sitting in the grass below, a small child with a round face, smiling.

*

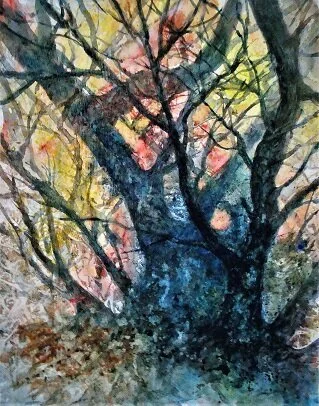

Me and my friend from the wooden house down the steep lane, we push our way through the head-high ferns to get to the dell. It is a deep, earthy bowl in the side of the hill. On one side is a huge beech tree, its silver trunk rising skywards and the branches fanning out over the dell casting it into mottled shade. A thick rope hangs from one of the lower branches. Tied to the end is a wooden crosspiece to perch on, and a cord to haul it back to the Leap. This is where I stand, high up on the edge of the dell, clutching the rope. Then I push off, my friend shoving me for good measure, and I fly away, lowering myself onto the crosspiece. I hurtle down, the earth roaring up to meet me, then swing clear and up the other side. I feel something inside me lurch as I sway back again. Back and forth, rocking back and forth till I subside. I swivel off the crossbar and hang from it, then drop to the ground. My friend hauls it back.

We are the only ones there today. We have our fill of risky thrills. Suddenly we hear the growl of a car engine labouring up the steep lane on the far side of the dell. Then a strange crumpling sound and the engine stops. We scamper up the bank of the dell and peer through the ferns. I know the car, an Austin 16 my father tells me. It belongs to the lady of the Big House. And there she is with one of the farmhands going round the back of the car. Attached to a rope is an invalid carriage. It is lying on its side, its black fabric sticking out at odd angles. I think it looks like a giant wounded bat. My friend knows who’s inside….the ancient woman who lives at the bottom of the steep lane, where we get bread. The lady from the Big House and the farmhand are dragging her out of the carriage and sitting her down on the grass verge.

My friend scrambles through the ferns to look. I get it into my head that the old woman would like some sweets. I come out of the dell and run along the ridge road to the little shop next to the school. I feel the heat of summer on my bare arms. By the roadside is a dead fox and a hum of flies. At the shop I buy a packet of Love Hearts and race back to the lane. When I arrive there is no one, nothing, to be seen. No car, no invalid carriage. Even my friend has gone. I wander home through the ferns, eating Love Hearts.

*

Another house, another place. The fallen tree trunk lies at the edge of the clearing in the wood. I think its roots crawl up into the air like a giant spider. K snorts and calls me an idiot. K is my best friend since we moved. He has to wear callipers, steel rods clamped to his thin legs with thick leather straps. But he can outrun me on his stiff, whirring limbs. He can also beat me up. I love him though. My mother disapproves.

Beyond the fallen tree trunk, in the clearing, stands the Scout Hut. K and me hide behind the trunk and watch them, the scouts, in their uniforms and green neckerchiefs fastened with a woggle. They parade up and down and pull a flag up the white pole. They chant something and salute. K thinks they are idiots too.

One day we see a crate of empty juice bottles outside the hut. We are playing dares.

Later, later, the episode becomes a poem….

It was his turn.

‘Smash those bottles then’, I said.

K stood there on his iron legs

and grinned wicked light.

‘Keep away from him, son. He’s common…..’

her standard rebuke. ‘Lead you astray, he will.’

But it was the boy in him I clung on to,

trying to keep up as he strutted ahead,

his callipers flying like fists.

So I lined them up

on the fallen tree. They glinted in the sun.

I handed him the stones, arming my god,

as K, pinned to the turf, swung and teetered,

hurled them like spat venom. Bottles

glittered like angels as they atomised.

K’s chest barrelled with pride.

‘ ‘s that good enough?’ he barked, and then,

‘Your turn now.’

And all I could do was squirm and smirk

and run home to my mother.

*

My bedroom is at the back. Below my window is a shed with a sloping tin roof. Beyond that, the garden stretching down to the woodyard fence. At the bottom stands an apple tree. One evening I intend to run away, stung by some felt injustice.

Decades later, and I am sitting at my father’s bedside. He has cancer and has been sent home to die. I remember…..

Home at last and sitting in lamplight

our quiet breath meeting

I adjust your hands on the sheet

and watch your eyes watching mine

wondering how much you know.

And think of the time

I slipped out of bed

climbed through the window

and slid down the lean-to roof

grazing my knees on the rust,

dropped to the damp earth below

and ran away.

To the apple tree at least.

I stood beneath it in my dressing-gown,

cold feet among windfalls,

staring back at the one lit room

and waited for you to come looking.

*

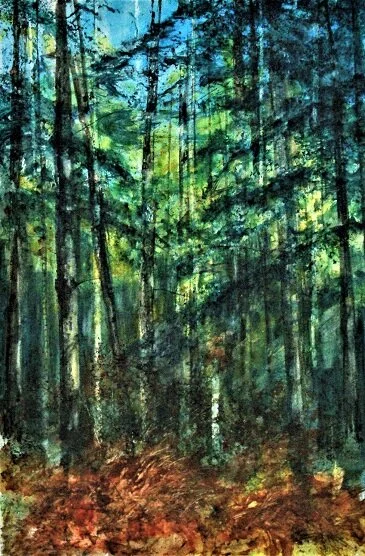

Yet another house, other trees. At the end of our garden is a line of larch trees. I am now ten. Larch trees are easy to climb, their branches sticking out from the straight, slender trunk like the rungs of a ladder. The higher I get, the more it sways and when the wind gets up it becomes a wild excitement. Below the trees is the railway cutting. A local branch-line carries a train every two hours, pulled by a black 4-4-2T steam locomotive. I perch in the treetop waiting for it. I lose myself in the clouds of steam and smoke.

Sometimes, instead of climbing a tree, I crawl through the wire fence and creep through the undergrowth to the edge, my knees scraping on the flinty earth. I am as close to the steep drop as I can get. I put my ear to the ground till I hear the rails vibrating, then the deep rumble as the engine approaches. It always keeps me guessing….when….when? And it is always suddenly….now! It bursts round the bend, pistons flying, billows of smoke, jets of steam erupting to fill the chasm and envelop my shuddering body. Then, when the clouds have settled to a drift of haze in the cutting, I crawl back through the fence and retreat up the garden path, rubbing the soot from my eyes.

*

*

Soon my junior school days are over. A letter arrives saying I have passed the 11+. I am given a bike. I must leave the trees to see the wood.