Prologue

Looking out of the window from my lodgement three floors up, all I can see is the swelling of waves coming in from the northern horizon. Apart from an annoying slice of Aberdeenshire I could surf to the North Pole without encountering land. I would squeeze between Orkney and Shetland. Jan Mayen Island would be well to the east and I would comfortably miss Svalbard. This is where I have come: the sea, the waves, the tides, and sky.

Where I was born, in the bottom dwelling of a hill of terrace houses in Bradford, then where I misspent my boyhood and youth in the valleys and beechwoods of the Chilterns, and where I lived and worked for most of my adult life in Wakefield on the southern edge of the great West Yorkshire conurbation….these places could not have been further from the sea.

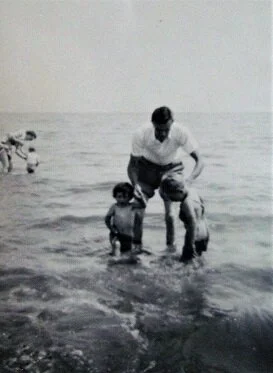

A wrinkled photograph shows my father in his shirt sleeves, trousers rolled above his knees, gingerly holding onto my sister and I in the shallow tide at…well, where? Bognor perhaps, or Littlehampton, where I puzzled over the way the sand was patterned in crinkly ridges, ‘the ribb’d Sea-sand’ of Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner.

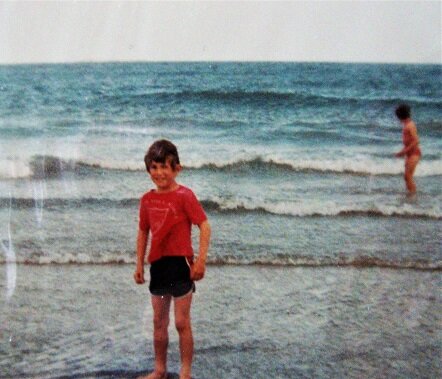

And there are pictures of my own children on a rare visit to the sea, tentatively exploring the strange element.

And that was it as far as the sea was concerned.

But now I look out from my crow’s nest across the wind-blown waters where the Firth of Forth and the North Sea meet. Over time my senses tune to sea colours — grey, green, turquoise, silver; sea sounds — deep turbine roar, rasping exhalation of wave-break, lisp of gentle tides; sea smells — salt and kelp and sea-wind.

And I am struck by the awesome realisation that waves have been breaking thus for millennia, long before there was a window here to look out of, and will do so long after it shatters to dust.

I never thought the sea was in my blood,

landlocked till now by hedge and drystone,

my tracks trained on rocky contour lines.

But now it’s my front yard.

Sitting on the wall watching it break and

spill between the red reefs at my feet

I try to learn its language, catch its twang —

the surf’s riff peeling along the wave’s crest,

the grackle of pebbles in the undertow.

And how it keeps on coming like an illusion,

the dark swell brimming with intent,

a dream catching its breath and dissolving.

At night with the window open

I hear the thump of its deep iambics

and feel its pulse beat in the sea-caves of my sleep.

So now when I’ve been to get my paper in the morning I walk back along the shore, the little bit of rocky beach below my dwelling. I stand for a few minutes watching the waves roll in from a hazy horizon. I keep the image in my head, go home and paint it

Morning Sea

The strata of old red sandstone, 400 million years old, on which our houses and roads stand, out of which the substantial villas nearby are built, shelve out from the beach, red-umber slabs to be eroded and chipped away by the next millennium of wind and tide. I do a few exploratory watercolour sketches….

Later, I do a painting of the breaking surf in acrylic.

And so begins this exploration of my new world: the sea, the wind, rocks and rockpools, the pine trees hanging over the low cliffs, and the cry of the curlew. But maybe not so much a new beginning as a recycling, for time does not travel in a straight line, but like a wanderer stops and starts, turns back on itself, spirals and, as with most of my own wanderings, ends up where it started.

As I walk along the shore, I sense the waves break into my mind, stirring my imagination. They also throw up the past, tossing its flotsam onto the shingle at my feet. Seascape becomes mindscape, shorelines become lifelines.