Boxed Sets

For those of you who turn for entertainment and solace, particularly in these lockdown days, to boxfuls of your favourite TV dramas — your ‘Game of Thrones’ or ‘Line of Duty’, your ‘Dads Army’ or ‘Last of the Summer Wine’ — I must apologise. Personally, I am not a great fan of drama, though I do have a weakness for crime series, particularly the Scandinavian variety such as ‘Wallander’ and ‘The Bridge’, and the terrific French one, ‘Spiral’, which I found utterly gripping. Even so, I would not contemplate sitting down and ploughing through all ten episodes at a go, ‘binge watching’ I believe is the term. I prefer the anticipation of waiting a week for the next part, ‘delayed gratification’ being another term.

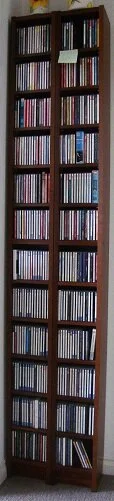

Which is all beside the point, because the ‘boxed sets’ I mean are of the musical kind. Having progressed through the whole gamut of earlier recorded music formats — 78’s, LPs, cassette tapes — I have come to rest with the CD. I know that CDs are now said to have a limited future but then so have I and with any luck I won’t outlast them. I also know that the popular way of receiving music now, especially among the young, is through the download. You simply sign up to Spotify or i-Tunes, scroll down to your desired piece, give your smartphone a little tap and away you go. But, despite the no doubt well-meaning advices from my offspring, I am not going down that route. For a start, what would I do with the thousand or so CDs I have ranged around my walls in historical order, like reassuring battlements behind which I can take refuge in my world of music?

Hidegard of Bingen to Brahms’ Requiem

Besides, I have a fondness for the CD itself, the physical object — compact, as its name suggests, easy to handle, handy in fact. I can listen, even to remastered recordings of historic performances, with none of the clicks and hisses and screw-ups of LPs or tapes.. I remember cleaning my LPs with something called Ex-static (groan!), a spray which came in a little bottle with a cube of sponge. You worked the liquid into the grooves then played the record. Afterwards you collected the accumulated gunge from the stylus. Apart from the convenient size of the CD, eminently storeable, and the quality of sound, I do like the little booklet which usually comes with the disc, full of biographies, analyses and song texts where relevant.

Tchaikovsky to Indian Ragas

Well, you have to put Ragas somewhere…and they are sort of timeless, aren’t they?

And so to boxed sets. I suppose my first boxed set was one I picked up in a second-hand shop when I was about seventeen. The school I attended had an adventurous and forward looking music teacher, Mr Flowerdew, under whose baton flourished an excellent orchestra and a choir in which I sang, a back row bass. I did once get a part in an opera we staged, Smetana’s ‘The Bartered Bride’. I played the bride’s father and appeared in only one scene. I had to sit in a chair looking grumpy while my ‘daughter’ elaborated on her current romance. Then I stood up, shook my fists in the air and sang, ‘I…I…I’ve no more to say!’ and stamped out. Not that I had said anything anyway.

I had rather more to do in the choir, however. Mr Flowerdew thought nothing of putting us through our paces and I particularly remember singing in Elgar’s ‘The Dream of Gerontius’, a work I have great affection for and have sung in a few times since in other choirs. As oratorios go it is not that lengthy, around an hour and a half. This is just as well since I am not a great lover of oratorios, but ‘Gerontius’ is an exception. Elgar, a Catholic, wrote ‘The Dream of Gerontius’ for the 1900 Birmingham Festival. It is a setting of the poem by Cardinal John Henry Newman, who had converted from Anglicanism, and it relates the death of an old man and the soul’s journey via Purgatory to the next world of everlasting life. There are solo parts for Gerontius, a tenor; the Priest and the Angel of the Agony, a bass; and the Angel, a mezzo-soprano.. ‘This is the best of me,’ wrote Elgar. ‘I have written my own heart’s blood into the score.’

Edward Elgar 1857-1934

It so happened that, at the time we were rehearsing ‘The Dream’ in the school choir, I was one day idling time away in a local junk shop when I came across a dusty cardboard box half hidden behind some chairs stacked on a table. Out of curiosity I opened it and within found a pile of 78 rpm shellac gramophone records. ‘The Dream of Gerontius’, on thirteen shiny black discs ! I read the labels: the conductor was Malcolm Sargent, the tenor was the renowned Heddle Nash and the choir the Huddersfield Choral Society. I bought the box for a pittance…the shopkeeper was glad to get rid of it, I think. I took it home, clutching it under my arm. It was quite a weight and I didn’t want to drop it.

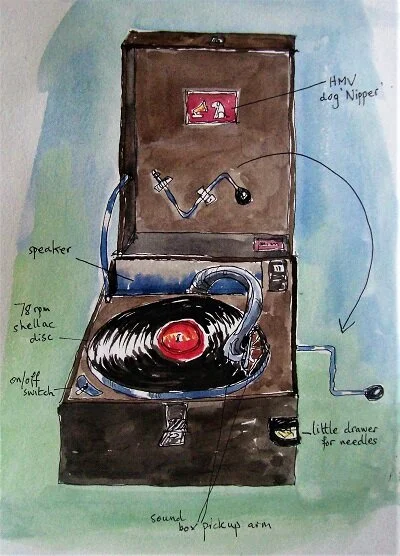

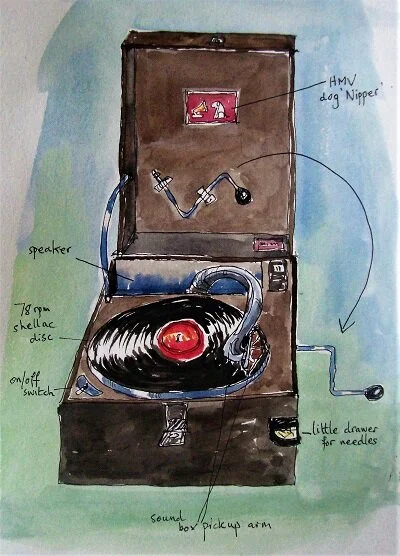

At the time, I possessed an HMV portable gramophone. It was black, about the size of a small suitcase. Inside the lid was a picture of the small white dog, Nipper, staring into the horn of an antique gramophone. The winding handle was clipped inside for carrying purposes and there was a small compartment for storing needles. Thus I listened to my ‘Dream’, following it in my vocal score. I should add that it involved physical as well as spiritual exercise, jumping up every three minutes or so to change sides, not to mention the frequent winding up required

My HMV Gramophone

That was my first boxed set, in a very literal sense of the term. My present recording of ‘The Dream of Gerontius’, the 1964 one under Sir John Barbirolli, fits comfortably onto two CDs, with room for the ‘Sea Pictures’ as well. A word must be said about this recording, still regarded by many as the finest, partly because of the sublimely luminous singing of Janet Baker as the Angel but also for the energy and emotional depth Barbirolli brings to the performance — the tenderness of the orchestral playing at the beginning of Part Two, the blaze of triumph in the ‘Praise to the Holiest in the Height’ chorus and the fiery snapping of the men in the Demons’ Chorus, this presumably after Sir John had told them, ’You’re not bank clerks on a Sunday outing, you’re souls sizzling in hell!’

Cardinal John Henry Newman 1801-90

In the days of 78’s a symphony or concerto would normally take five or six records. They often came in the equivalent of today’s boxed set, a handsome album with embossed gold lettering with the discs in stiff cardboard sleeves within. I once possessed such an album which contained Richard Strauss’s symphonic poem, ‘Don Quixote’, a graphic musical depiction of the eccentric knight’s escapades complete with a wind-machine and brassy imitations of bleating sheep. It was recorded in the 1940’s with Strauss himself conducting the Vienna Philharmonic. This album occasioned my first experiments with a reel-to-reel tape recorder. I stuck the microphone in front of my gramophone and played through the set of records, stopping and starting the tape at each side change, until I had a complete, uninterrupted performance on tape. I just hoped that during recording no one decided to go to the loo which adjoined my bedroom. But the effort was well worth it and fed my burgeoning adolescent addiction to music.

Richard Strauss 1864-1949

I now possess a boxed set of all Strauss’s orchestral works — seventeen pieces in all, getting on for eight hours of music, on seven CDs in a little blue box complete with a thirty page booklet (though half of it’s in German) That’s my kind of boxed set.

I don’t know how far advanced I am along the autistic spectrum but I have to admit that the boxed set satisfies my need for completeness. It is not enough for me to have one Beethoven piano sonata, for example; I have to get the lot, all thirty-two of them….and then further sets for comparison! Thus I have acquired many boxed sets — Mozart Piano Concertos, Schubert’s Sonatas, sets of symphonies by Brahms, Tchaikovsky, Sibelius, and many more. I even have a boxful of Wagner’s ‘Ring’ Cycle, three inches thick, but I must confess I have never summoned the required stamina, or the inclination, to listen to it all the way through.

We have been in lockdown of one sort or another for over a year now, and in that time my boxed sets have come into their own. For a start, I have spent more time in my art room, even if it is just to doodle or scribble things down. Music is a constant companion; it is particularly convenient to have a boxed set on the go. There are three in particular I will mention, partly because they have taken me from my usual comfort zone of background music — Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Brahms maybe — into relatively new territory.

I have never been much of a Bruckner enthusiast, even though I find some of his passages very stirring and grand…and he is good at endings! I have often been exasperated, though, by the way he gets going with some exciting theme and then just stops, for some rather insipid stuff to meander in until the ‘big’ sounds appear again. But one Saturday morning I happened to hear Tom Service, one of BBC’s music experts, talking about the Sixth Symphony on Record Review, and he began to make sense, to me at least, of Bruckner’s composing methods. More to the point, perhaps, the version he recommended was the one I happened to have, complete, of course, with all the other eight symphonies in a pale green box with the face of the conductor, Eugen Jochum, in a white turtle-neck sweater, looking out. I began to go through the symphonies one by one. I was struck by the early ones, No’s 1 and 2, which are rarely performed but in my view bear comparison with the later, more popular ones. At times the excitement of gigantic Bruckner climaxes got to me and I was in danger of losing my paintbrush in a flurry of ‘air’ conducting. I listened to these lengthy works a number of times and, though I have put the little green box back on the shelf for now but it will not stay there long. I feel I am more in tune with Anton Bruckner now.

Anton Bruckner 1824-1896

Another boxed set which landed on my doormat with a satisfying thud was the complete String Quartets of Dvorak. I have always liked his symphonies, especially the Seventh, the Cello Concerto and odd bits of chamber music such as the Piano Quintet, but though I was aware that he had written numerous string quartets, fourteen as I discovered, the only one that ever seemed to be played was the 12th, known as the ‘American’. It was written in 1893 while Dvorak was in the States teaching and conducting. Like the famous Ninth Symphony, ‘From the New World’, it incorporates elements of American folk music. And, indeed, it is a very engaging and tuneful piece, but what of the others, I wondered. So I ordered my box, a dark green one this time, with a picture of a Bohemian flower meadow on the front. There are ten discs in all and the artists are the Stamitz Quartet, a Czech group who play this music very idiomatically. I was surprised to find that the earlier quartets, dating from the 1860’s were so long — the 3rd lasts 72 minutes. I did not find these pieces particularly memorable — it is as though Dvorak is rather painstakingly finding his way in this form. Yet by the time I got to Quartets No’s 5 and 6 and beyond, a more familiar Dvorak emerged: tuneful, generous, expansive but concisely structured and with that positive energy that makes his music so attractive. Not that the music lacks tenderness and sensitivity. The Ninth String Quartet, in D minor, was composed just two months after the deaths of two of his children, one at ten months, the other at three years old. The third movement, with its muted, wistful tones seems to be a memorial to them.

Antonin Dvorak 1841-1904

Lastly, partly because I happen to be listening to them now, are more quartets — just about my favourite musical medium, you may have gathered — this time by Dimitri Shostakovich. Here is another composer I have had mixed feelings about. Like many listeners I think the Fifth and Tenth Symphonies are tremendous in their range of expression and impact, but some of the others, particularly those depicting some aspect of war or revolution, I find frankly somewhat tedious. Music critics have similar mixed resposes. One writes of ‘a musical language of colossal emotional power’ while another dismisses it as ‘battleship grey in melody and harmony — all rhetoric and coercion’ Yet I always thought I was missing out on something in being unacquainted with his fifteen string quartets. Two artist friends of mine were once engaged in a project to produce pictorial responses to Shostakovich’s quartets and ever since I’ve meant to get to know them. Earlier this year I ordered a boxed set, a fairly slim box, this one, with, appropriately enough, a red square in the middle of the cover and a small hammer and sickle in its corner. Peering out from behind are the rather ghostlike, thickly bespectacled eyes of Shostakovich himself.

For some reason I felt a little daunted by the prospect of going through this music, but in fact I’ve become hooked on it. The quartets are given terrific performances by the Emerson Quartet, performing in the 1990’s live at the Aspen Music Festival. The players transmit to great effect the range of moods and feelings in these quartets, the products of Shostakovich’s intense and restless personality. There is both gravity and wit, optimism and deep melancholy. Indeed, the funereal gloom of the last quartet, written shortly before the composer’s death in 1974, caused some members of the audience to walk out. I do not listen to that one often, but I understand the Emersons when they say that performing this music live always brings about a palpable response in the audience — they regard the quartets as ‘theatre pieces’. Certainly, the drama of these string quartets has kept me intrigued and entertained for the last few months

Dimitri Shostakovich 1906-1975

I have found, listening to these boxed sets over the past year, even when they pale into a sort of background wallpaper, that I have somehow got into the minds of these composers and been with them on their own musical journeys. And so I am grateful for these little cartons of digital delight for providing me with so much enjoyment and stimulation.

I doubt if I will tire of my boxed sets but if and when I do I might be persuaded to go and buy the complete set of ‘Spiral’ DVDs.