Sunday Morning

It is Sunday morning and a dull, misty one at that. Just coming up to 5 am and I reach out to flick my little transistor radio on. The World Service news…it’s good at this hour to get information that is not London-centric, news from Peru, Afghanistan, India, Mali. Then Radio 4 takes over with the morning litany of the Shipping Forecast. My ears tune in to ‘Cromarty, Forth, Tyne’, and the Inshore Waters ‘from Rattray Head to Berwick-upon-Tweed’. That tells me all I need to know about the weather for today. There follows one of those holy relics of BBC tradition, ‘Bells on Sunday’, a cacophonous peal from St. Thingamejig- in- the Vale. I do like the arcane language of campanology though: ‘The tenor, cast in 1729, is tuned to E flat and weighs 15 cwt. We hear them ringing a touch of Avon Delight Maximus.’ At least it’s better than ‘Prayer for the Day’ which ironically is not broadcast on Sundays.

My tea-pot and large cup

I get up, pad into my kitchen and make a cup of tea, a large one. For this one cup I use real tea — unbeatable — but for the rest of the day a tea-bag will do. I take the tea back to bed and start scribbling things down in my desk diary, any ideas, plans, lists, memos that come to mind. I also write in my journal which I never feel inclined to do at night so leave till the following morning. Since boyhood I have been an obsessive scribbler….maybe it’s the fear of my thoughts and observations disappearing without trace. I feel I have to capture them in my notebook. I like to write on unlined, plain pages with a mechanical pencil.

This morning I decide to have breakfast in the Garden Centre which has just reopened after the pandemic closures. To get a bit of exercise I’ll take a roundabout route. The shore stretching eastwards from my flat skirts the golf course for a couple of miles before widening out into the sandy arc of the beach at White Sands. Golf rules in these parts and even the renowned John Muir Way which I am following has to stick to a narrow path along the shoreline defined by red stakes. The golf club got very jumpy during lockdown, when play was not allowed, and they erected ‘Keep Out’ and ‘Follow the Red Stakes’ signs and roped off the fairways. People had been spotted actually walking on the empty golf course! Scottish law declares that at all times golfers have precedence over the humble walker. I have been bellowed at on more than one occasion for being in someone’s sightline and felt the draught as a golf ball whizzed past my ear. Not that the portly gents in knee-length shorts are always as good as they think. On my wanderings up and down the pebbly shore I have accumulated a fair collection of stray golf balls. They provide amusement for my grandson.

Stretching out into the sea at right angles to the shore are the serrated ribs of red rock thrusting up at a 45 degrees from the beach. I try to imagine the tremendous forces which buckled these 400 million year old rocks into this incline.

I approach Fluke Dub, a shallow lake left behind whenever the tide retreats. In Spring I watch out for a pair of sheld-ducks who come here to rear their brood — there were five this year. They are fiercely protective birds. When they are out on the Dub giving the young their swimming lessons I have seen them harried by carrion-crows or black-backed gulls on the lookout for easy pickings. The sheld-ducks rear up in an angry whirl of wingbeats and water and see them off.

Today there is the truculent piping of oyster-catchers circling the rocks, cormorants spreading their broad wings out to dry, gulls — herring, common, black-headed —, redshanks bobbing about in the shallows, and there, statuesque near the edge of the Dub, a solitary heron.

Patrick

I call him Patrick in memory of a bird of the same species who used to station himself by the weir beneath the Hepworth Gallery in Wakefield. You could observe him from the room which contained not only sculptures by Dame Barbara herself but works of other St. Ives artists, including, of course, Patrick Heron.

Suddenly, I flush out a small brown bird onto the path in front of me. It is a young skylark. It trots along before me. It seems reluctant to fly away but eventually, when I bend down to take a photo of it, it does.

Good speed, little skylark

Two sturdy ladies bustle by pushing their golf caddies, making for the green where they have managed to land their balls. Addictions can take many forms, prodding a little white ball into a hole being one of them. Mine, one of them anyway, is walking the shoreline with all that it manifests.

I am logging the plants also. The deep yellow flowers of the sow-thistle make a colourful border to the shore now, along with the white, daisy-like flowers of the sea-mayweed. Yarrow lines the path, along with white and red campion and sea-rocket…also scurvy-grass, its fleshy, locket-shaped leaves apparently a good source of Vitamin C. Poppies and delicate harebells complete the colour-wheel of wayside flowers Here are some: white campion, harebells, perennial sow-thistle going to seed, and sea- mayweed…..

Soon I reach a point where the shore reaches out in a wide, flat platform on which stand rock outcrops, eroded away over the centuries into striking sandstone configurations.

The Rocks, watercolour on gesso ground

I often take a little detour and poke around these rocks for a while. Once, I was rewarded with the sight of a little group of ringed-plovers probing the shingle for food. Today, I am fascinated by the almost abstract pattern formed by the grooves and cracks in the flat rock and the green bladderwrack upon it.

I rejoin the path, walk round a large clump of sea-buckthorn and there ahead of me is the aptly named White Sands, a pleasing beach backed by dunes in a gently curving bay. Coming by road for the first time you would be forgiven for having doubts about the place, since you pass by a towering cement works on the way. But not to worry; once you are sitting on the beach or having a dip in the sea the works are out of sight. In any case they are part of the history of the place. Limestone has been quarried here for centuries and at the southern end of the bay lie the substantial remains of an old limekiln with three large archways leading to what used to be the furnaces. Along the shore you can still see embedded in the rocks rusting iron stakes and mooring rings where boats would draw up to transport the lime up and down the coast. There are also the vestiges of coal measures to be seen in the sedimentary strata lining the shore, reminding me that here and further west towards Edinburgh coal-mining was once a flourishing industry.

Now, post-lockdown and school holiday time has attracted campers and vans to settle at White Sands, which is fine but I wish some people would have a bit more sense. I find my path, which is narrow enough anyway, blocked by a tent pitched right across it, with two spent barbecue trays dumped in the grass. I stop and address the tent in the hope of getting some explanation but it is empty. Maybe the occupants have just left it and gone home. It seems that camping equipment, even the tents themselves, have become disposable items if reports from the Lake District are to be believed.

As I gain the narrow road to circle back to Dunbar I recall a day in quieter times when I came here with the grandchildren and sat on the beach while they played in the rockpools. I wrote a poem about it.

At White Sands

….the brimming sea

flint-green and the weight of stone

heaves against the rim of bleached sand.

Above the shivering dunes

wind-driven gulls hone their wings

to silver blades.

A child among the rockpools

crouches over a mirror of still blue,

sees her own face shining back

and her finger closing in on itself.

Out in the bay breakers gather and collapse.

To my left is the cement factory and a small lake, a flooded quarry. Two roe deer appear from nowhere and delicately negotiate the wire fence before scampering over the road into the woods on the other side. The woodland surrounds Broxmouth House. The 18th century mansion cannot be seen from the road, but the earlier structure was used as a command base for Cromwell during the Battle of Dunbar in 1650. The place is now used for holiday lets and weddings. A little further on I notice a car parked up on the wide grass verge. I have seen this car parked here before and, looking over the fence into the rough field overlooking the quarry lake, I once again make out the form of a woman crouching down, motionless, in the grass. Is she an entomologist, a birdwatcher, an artist, a mystic, a madwoman? Who knows? Good for her anyway. I respect people who can sit unabashed in the middle of a field.

Now I follow the road back but after half a mile or so veer off onto an abandoned road, a relic of the old A1, now bypassed by the modern motorway. You can pick up bits and pieces of the old road for twenty miles in either direction from here. I like these crumbling tarmac ghosts of roads as they slumber, unharassed by traffic, reverting to nature. Even though it’s a dead end, large concrete blocks bar the way. These, I believe, are to deter travelling folk who once set up an encampment here. I can’t see how they were inconveniencing anyone in this dead end of a road to tell you the truth. Better than squatting on a school playing field or public car park. Mind you, I was once walking across a field down by the canal in Wakefield where travellers had set up camp when a particularly vicious little dog chased after me yapping wildly and bit me on the ankle. I cursed the dog and its owners roundly.

I walk under the railway bridge just as a Cross Country Express shoots southwards. I could be on that, I muse, visiting my son and his family in the said Wakefield. Later, perhaps, later. The defunct road dwindles to a narrow footpath and, then, a little epiphany — in the deep hedgerow, the translucent scarlet berries of the guelder rose, its three-lobed leaves just fading into yellow, and, alongside, the last pale pink flourish of the dog-rose. Such sights lighten the heart. Here are the guelder rose berries and the bush, the dog-rose and emerging blackberries.

I emerge from the footpath onto the A1 itself with the traffic speeding by. My nature walk is not quite over though, for there, through the hedge to my right, is a large bear.

The Bear

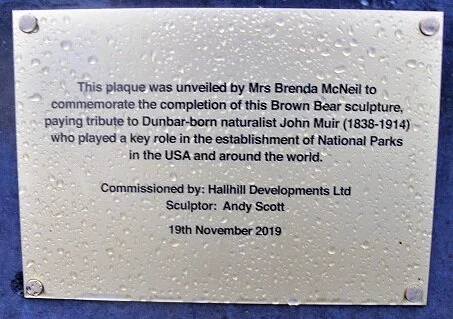

The sculptor, Andy Scott, who was responsible for the giant, 30 metres high Kelpies, those huge horse heads which tower over the Forth Clyde Canal near Falkirk, was commissioned to create a bear as a memorial to the great naturalist and conservationist, the Dunbar born John Muir, who presumably encountered many such bears on his wanderings in the Rocky Mountains. And so it came to pass, a mere sixteen foot, however, but impressive all the same, a bear up on its hind legs made of perforated bronze.

Our Bear

And so we have our Bear,

his sculpted bronze winched to his plinth

between McDonald’s and the motorway.

He rears tree-high and paws the air,

is riddled with artful holes

as from a double-barrelled blast --

constellations to let the sky-light through.

We tread the tarmac path

to read the plaque and take our selfies,

the giant grizzly of John Muir’s dreams

become a Facebook ‘like’, snapped

and instagrammed while infants stroke his feet.

When daylight fades and his stars go out,

I fancy his empty head looks up and sighs

to see another, greater Bear climb up the skies.

A few yards beyond the Bear I climb through a fence into the precincts of McDonald’s where even now motorists are queueing up to collect their hamburgers and cartons of chips. Beckoned by the huge luminous green logo of the temple of Asda I go down, don my blue mask and buy my paper. Then to the Garden Centre next door. I follow the arrows and enter by an unaccustomed door. I have to give my contact details but, though I can just about remember my name, my phone number deserts me and I haven’t brought my mobile with me. (Yes, dear reader, I actually used a camera to take the pictures) The woman smiles pityingly and says not to worry, which I don’t. I order my breakfast and sit at my widely spaced table, thankfully taking off my mask, and wait for the food to be brought to me. Not bad this…may the pandemic continue. I read my paper, searching in vain for evidence that our world leaders are doing anything remotely intelligent or civilised to deal with the enormous problems that beset us — the infantile Trump, the delusional Bolsonaro in Brazil, the arch-poisoner Putin, the megalomaniac Lukashenko, the ethnic cleanser Xi Jingping. I suppose we should be thankful that we have only the buffoon Boris to put up with.

I have a very satisfactory breakfast of fried egg, bacon, sausage, beans and a potato scone and yet more tea. Then I get up, ready to go home. I head for what I foolishly assume is the exit but find myself pointed by red arrows into a one-way system. I seem to be heading for the plants department but, no, I am directed through garden furniture, only to be confronted by ‘No Exit’ signs. I sneak through the country clothing area with its ankle length waterproofs, broad-brimmed hats and long wooden crooks for people who like dressing up as shepherds, then find myself hemmed in by shelves of home ‘crafted’ fudge and crystal bonbons, whatever they’re supposed to be. I feel as though I’m trapped in a sort of purgatorial Ikea or one of those dreams where you’re trying but never quite succeeding in escaping from a maze.

I call across the confectionery to a young lady at the till. ‘Excuse me, sorry to trouble you, but how do I get out?’ ‘Oh, just through here,’ she says, pointing.

It’s easy really. You just walk out.