Another Wood

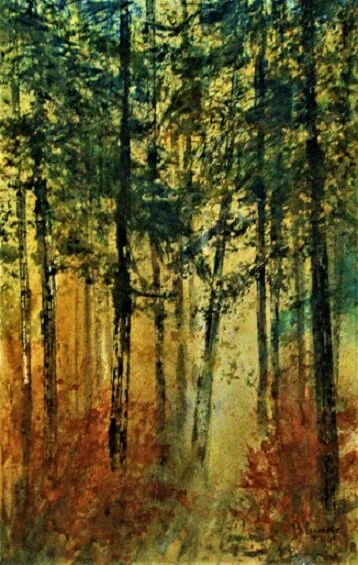

Sometimes I come here to escape the winds — almost a constant in these parts — but mostly for the peace. It’s not a long walk. I can make a circuit round the periphery in less than an hour. As I walk along the southern edge of the wood, there is a drystone wall to my right and open fields — that low limestone scar badged with gorse and a copse of windblown pines on the skyline. To my left is the body of the wood, mostly conifer in this part but not oppressively so. There are deciduous trees shedding more light and a vigorous understory. I round the top of the wood with a last glance over the wall, in time to see two crows, slow wings beating, tracking over the fields like low-flying bombers.

At this end of the wood great stacks of felled timber line the track as forestry work proceeds.

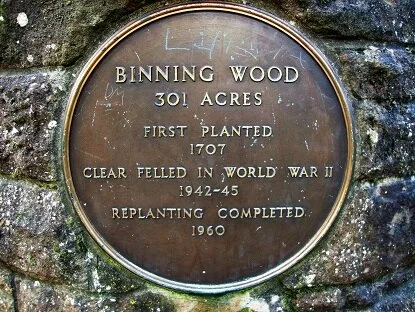

I arrive at a large circular space, like a hub with paths leading off like the spokes of a wheel. In the centre is a low stone monument which informs me that this is Binning Wood.

Binning Wood is part of the Tyninghame Estate, the family seat, at least until 1987, of the Earls of Haddington. The creation of the wood is down to the efforts of Thomas Hamilton, the 6th Earl, and his good wife Helen. After his marriage, at the precocious age of sixteen, he inherited the estate and found it in a state of some dereliction. The tenants, apparently, had ‘pulled up the hedges, ploughed down the banks and let the drains fill up’. Thomas set about restoring the landscape in what were at the time innovative ways. After his death, a book was published based on his own notes, ‘A Treatise on the Manner of Raising Forest Trees.’ Helen was a keen arborealist too, and was largely responsible for Binning Wood. The original plan was based on continental models strongly influenced by classical traditions, a symmetry of pathways radiating from central ‘hubs’.

Thomas Hamilton, 6th Earl of Haddington, and his wife, Helen Hope.

During the Second World War, much of the wood was felled, the timber being used for the airframes of Mosquito fighter-bombers. It was replanted with conifers but, like many other local plantations, is now being rearranged — the conifers culled and replaced with native deciduous trees.

*

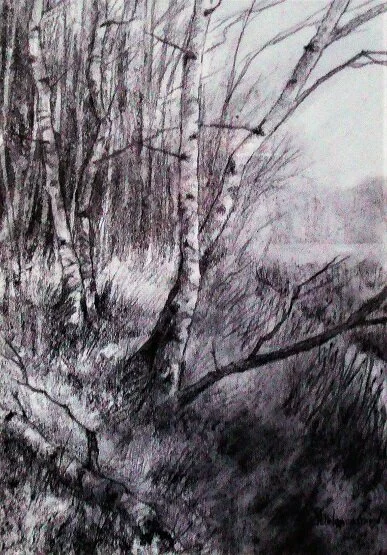

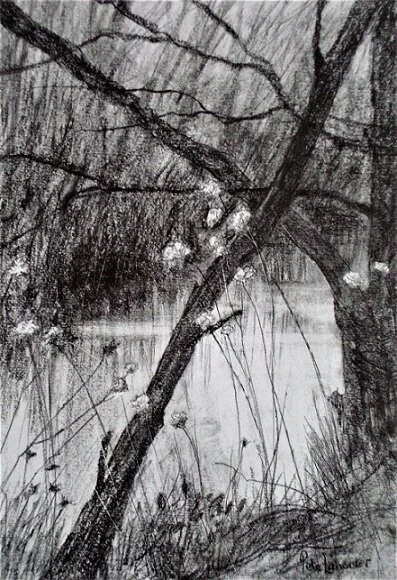

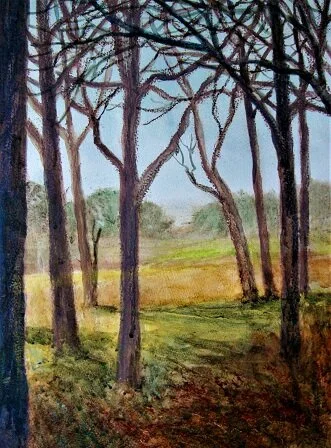

Perhaps my favourite part of the walk is the return leg, where the forest track narrows to a woodland path and the conifers give way to beech, oak and silver birch. The path skirts the northern side of the wood and along the boundary runs a small stream, Peffer Burn, which a mile or so further on issues into the Firth in sight of Bass Rock. Here are a couple of pencil sketches of the edge of the wood — a young birch, reflections in the stream, fields beyond.

A little further on I come to a wide airy space of tall beech trees, the spring light filtering down to the woodland floor. This is the Memorial Wood. Here you can be interred in a wicker basket and have a small inscribed stone embedded in the leafy earth to denote your whereabouts. I have to admit that I wouldn’t mind ending up here.

I see ahead of me a man standing among the trees. He is middle-aged with a round face, a smiling face. He is wearing a wide-brimmed, floppy hat. He looks up as I approach and we exchange the usual pleasantries. But then he goes on, ‘I’ve been talking to my brother.’

‘Oh,’ I say, and add, somewhat randomly, ’And how is he?’

‘He’s fine. He died five years ago, but he’s happy here among the trees, and that makes me happy too,’ he beams.

‘That’s good,’ I say. ‘Do you often come to see him?’

‘From time to time. Today’s his anniversary, you see. I’m going to spend a little more time here, then I’ll go.’

‘I’m glad you’re both happy,’ I say.

‘Thankyou,’ he says, and we part.

*

Who am I to gainsay his encounter with his departed brother? A natural scepticism makes me doubt the existence of ghosts. I don’t believe in spirits, the afterlife, heaven, God. I assume, perhaps stubbornly, that once you are in your coffin and buried, or burnt and your ashes scattered, then you are done…’deceased, demised, no more, a late parrot’, in the words of the Monty Python sketch. I can’t see why some people feel they must arrange their own funerals — what music to be played, readings to be read, the food to be provided, where their remains are to be strewn. Funerals, surely, are for family and friends. It’s not how you want to be remembered that’s important, but how they want to remember you.

But this scepticism, some might say, is my loss. Perhaps life is richer, less bleak, the more you invest it with myth. Those who plan their own funerals are just rounding off the legend of their own lives, putting the finishing touches to their own self-portraits. And why indeed do I admit to wanting to be buried in this wood? After all, I won’t know anything about it. It is but a whim, a fancy that feeds into my living imagination, just another of the fancies that weave the web of illusion and fantasy that is our lives. This particular one fits into my present way of conceiving my life, a life I am constantly reinventing. When I lived in Yorkshire, before I even knew of the existence of Binning Wood, I used to frequent the Washlands, a place I became attached to and identified with, an inspiration for my creative life. It was bounded by the Aire and Calder Navigation. At that time I entertained the thought of having my nearest and dearest toss my ashes into the canal.

*

So I leave the man in among the beech trees communing with his brother. I do not dismiss him as foolish or deluded. I am, in fact, genuinely moved. It doesn’t matter whether it is literally ‘true’ or not, but that he imagines it to be so and it makes him happy. And there are many ways to have a conversation, not least the practice of talking to oneself. I come away a happier and a wiser man.

*

Just down the road from where I live is the town cemetery. It is surrounded by open fields and, beyond, the sound of the sea. I sometimes go there, potter along the rows of graves reading the epitaphs, then have a sit down.

It pleases me to sit in silence here

facing the sun, out of the wind,

with the dead lined up in patient queues

chatting, no doubt, about the weather,

some ailment, or the weekend match.

Then, when the flowers have faded

and the grief, I imagine them one night

— beloved dads and mums much missed,

lads lost before their time and breathless babes —

get up and leap the boundary wall,

scamper away into the fields beyond,

holding hands with laughter in their eyes,

dancing off into the waiting starlight.