The Proms

As I write this the weather forecaster tells me that this is the end of Summer, meteorologically speaking at least. For me that has always meant also the end of two diversions that have amused and inspired me over the last sixty years or so — Test Match cricket and the Proms, not those end-of-year high school extravaganzas, I hasten to add, but the two month long festival of music held yearly in the Royal Albert Hall. This year, of course, the customary pattern of events has been severely disrupted. We were lucky to get any cricket at all, but thanks to the efforts of the organisers and the goodwill of the teams we managed two short series, against the West Indies and Pakistan, played to empty stands but entertaining and exciting nonetheless.

As for the Proms, I tuned into the first live one a couple of days ago, the first six weeks having been cancelled. At least we now have a fortnight of music making in the vast spaces of the Hall and wonderful it is, like taking a draught of pure water after weeks in the desert. The main work in the opening concert, given by the BBC Symphony Orchestra under their conductor, Sakari Oramo, was Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the ‘Eroica’. When it was first performed in 1804 it stunned and puzzled the audience with its length and power. For the composer it was a defiant affirmation of his faith in the egalitarian ideals of the French Revolution. The story is well known that he originally dedicated the work to Napoleon — he called it his ‘Buonaparte’ symphony — but when his friend, Ferdinand Ries, broke the news that the figurehead of the Revolution had declared himself Emperor, Beethoven raged, ‘He is now a tyrant…he will trample underfoot the rights of man!’ He then tore out the title page of his score and obliterated the dedication. It then became the ‘Eroica’.

Beethoven scratches out Bonaparte’s name

As I listened to this fine performance I felt the music echoing back through the centuries. Perhaps we could hear in it a defiant determination to overcome our present crises….pandemics, racial conflicts….and also a timely admonition to those world leaders who set themselves up as demigods, denying the existence of the crises or exploiting them for their own political ends.

The other work in this opening concert was Aaron Copland’s ‘Quiet City’, written in 1939 for trumpet, cor anglais and strings. It is a still, meditative piece but with restless undertones. I couldn’t help thinking of the far from quiet state of several American cities at the present time.

My painting of Quiet City, and the opening page of Copland’s score….

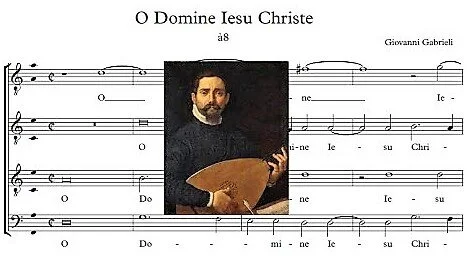

A few nights later the Hall was graced by the London Symphony Orchestra under Sir Simon Rattle. Ever imaginative, he decided to put the empty spaces of the building to musical use by programming two of Gabrielli’s Canzons for brass consort.. Giovanni Gabrielli (1550-1612) was a Venitian composer who wrote music for St. Mark’s Basilica, exploiting the galleries of that huge edifice for antiphonal effect, the phrases echoing each other across the airy spaces. Rattle replicated this by placing the brass sections around the upper tiers of the RAH to thrilling effect.

Giovanni Gabrielli

There followed two of my favourite pieces of music: Elgar’s ‘Introduction and Allegro’ for strings….a nice contrast to the preceding brass sounds, and Vaughan Williams’ Fifth Symphony. In this piece I heard, whimsically perhaps, a different kind of response from the ‘Eroica’ to our present condition. It is a serene, meditative work, not without enigmatic elements, the second movement marked presto misterioso , for example. It is worth remembering that it was written towards the end of the Second World War and that, in the First War, Vaughan Williams had served as a stretcher bearer. A vision of peace, not just for the war-weary society of 1944 but maybe for our times too.

Ralph Vaughan Williams, stretcher bearer, and Edward Elgar

The performances were, like the cricket, played to an empty house, but the atmosphere was far from flat or bleak, the stage beautifully lit in blue and white segments and the whole auditorium sparkling with a mini-galaxy of lights. There is, of course, nothing like the buzz of a live audience, the Prommers in the arena standing just a few feet away from the conductor, to create that sense of excitement and rapport in a musical performance. Yet I thought the musicians, despite their ‘social distancing’, played with great commitment and unity — perhaps sitting six feet apart made them listen to each other even more intently. And I for one do not miss the barrage of coughs and sneezes which often accompanies live performances. There always seems to be someone who waits for the quietest few bars to unleash a raucous bronchial eruption.

Another thing I don’t miss is the habit which has crept in over the last few years, and seems only to occur at the Proms, that of clapping between the movements of a symphony or concerto. I admit that this is a ‘grumpy old man’ moment and I am well aware that in the past audiences clapped not only between movements but at every available opportunity, sometimes even demanding encores there and then. But I find it a needless distraction, an example of modern man’s inability to endure even a brief silence. I think of a symphony as a unity, its four or however many movements belonging to each other in an organic whole, and the silences between them part of that whole, just a few moments for reflection and mental preparation.

An example. Here is Tchaikovsky….

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-18930

Perhaps the most blatant offenders are those who burst out clapping after the third movement of his Sixth Symphony, known as the ‘Pathetique’. Of course it sounds like an ending, loud and conclusive — the brass plunging down the scale to the final chords. But it isn’t the end. Tom Service, the music broadcaster, says of the third movement that it has ‘a seething, superficial motion that doesn’t go anywhere….it is an empty victory’. I agree with him, and good performances bring out that element of desperation. So to clap at this point is to miss the whole point of the way Tchaikovsky has structured this last and most emotional of his symphonies. For, following the relentless march of that third movement is the searing outcry on the strings of the real last movement, a slow, passionate stretch of music….call it grief, despair, resignation…which in the end dies away to nothing. To clap after the third movement spoils the whole intent. Indeed, I have known conductors dive straight into the fourth movement without a break in an attempt to quell unwanted applause. It is interesting to note that at one time the Soviet authorities changed the order of the last two movements in performance so that the symphony might end on what they assumed was a triumphant note.

During the earlier, cancelled, part of the season, the BBC treated us to past performances of note from the archives, some of which I remember from their original broadcasts. Carlo Maria Giulini conducting Brahms — the Second and Fourth Symphonies — in 1994, in a way many would now regard as too ‘romantic’, with those slow tempi and a lush expressiveness which is out of fashion, lighter textures, springier speeds being today’s trends. Great music can withstand whatever treatment it is given, though, and I was happy to indulge myself in Giulini’s Brahms. I thought the last movement of the Fourth, with the mounting excitement of that passacaglia, was tremendous!. Moreover, he drew that rich sound from the EU Youth Orchestra.

Carlo Maria Giulini (1914-2005)

Then there was Colin Davis and the LSO doing Beethoven’s ‘Pastoral’ Symphony, my favourite of the nine. Also in the programme was the haunting ‘Rose Lake’ by Michael Tippett. Written in 1995, its translucent orchestration evokes the scene of a lake in Senegal which changes colour through the day. But the most memorable archive recording was the stupendous performance of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony given by Leonard Bernstein and the Vienna Philharmonic in 1987. Bernstein was a Jew as was Mahler, who had received hostile anti-Semitic treatment from the same orchestra when he conducted it some eighty years earlier. It therefore gave Bernstein special satisfaction to conduct this symphony with that orchestra. It was indeed a blazing experience. Only three years later Bernstein was dead, buried with the score of Mahler’s Fifth Symphony across his heart.

The adagietto of the Fifth Symphony, Mahler and Leonard Bernstein (1918-90)

I started going to the Proms in my late teens when classical music had taken hold of me. Many a youth of the same age would play air guitar to their favourite rock bands. I would air conduct to what was then the Third Programme, the music issuing from my tinny little radio. I fashioned a baton out of a sliver of garden cane, painted it white and wrapped rubber bands round one end for a handle. I knew that Adrian Boult used rubber bands to stop his extremely long baton flying out of his hand.

I would get the Metropolitan Line up to Baker Street, then the Circle to South Kensington and walk up the road to the Royal Albert Hall. There I would queue with the other Prommers, not for the Arena though, the circular area in front of the orchestra. I preferred to go up to the Gallery. It was less crowded up there and you could genuinely ‘prom’, walk around on the soft grey linoleum, or sit against the back wall and just listen. If you wanted to see the orchestra you had to lean over the balcony, from which you’d get a superb bird’s eye view, could watch the conductor from the front….and study his baton technique! I still sometimes in my old age find myself waving my arms about when some particularly exciting music comes on. Thank heavens there’s no one around to see me.

Muse

Seraphic in her white dress inlaid with intricate azure,

her fingers fanning the flickering keys, adept and sure,

she’s rescued this hour from a day of dubious choices.

The clean lines of the arietta, the way theme chases

theme in the counterpoint’s logic — it’s a paradigm

of passion caught and fashioned, art’s stratagem.

Conspiracy of dancing notes, its take on beauty fearless,

the sonata’s complete, leaves no unfinished business.

I’m stunned by the current of that genius flash

wiring the matrix of her brain to the flesh

of her fingertips. Into the milling maze

of afternoon traffic, I take her with me, my seraph, my muse.

There have been Proms memorable for other than purely musical reasons. I was not there in person but I recall listening to a Prom in 1974 when Andre Previn was conducting Carl Orff’s ‘Carmina Burana’, a setting of bawdy texts in Medieval Latin satirising the Catholic Church. Thomas Allen was one of the soloists and half way through one his pieces he swooned and fainted. As he was carried off backstage to be revived, a young man from the audience emerged and offered to take over the part — his name was Patrick McCarthy. He knew the piece and had sung it before. He soon appeared in hastily donned evening-dress and clutching the score, led on by Previn. He sang the part most competently to the delighted applause of the audience.

A medieval manuscript of some of the Carmina Burana

Perhaps the most notorious episode in the Proms’ history was the night of August 21st 1986. I was sitting at home listening. The international news was dominated by Russia’s invasion of Czechoslovakia the previous day. Soviet tanks rumbled into the streets of Prague to crush the democratic uprising of the Prague Spring led by Alexander Dubcek. The programme for that evening’s concert was full of painful ironies. The orchestra was the Soviet State Symphony Orchestra on their first ever visit to London, under their conductor, Evgeny Svetlanov. They were to play the Tenth Symphony of Dmitry Shostakovich, himself once a victim of state censorship. In addition, the first half was to be devoted to the Cello Concerto of Czechoslovakia’s most famous composer, Antonin Dvorak, a native of Prague as it happened. It was to be played by the brilliant Russian cellist, Msistlav Rostropovitch.

There had been demonstrations outside the hall, some led by the political activist, Tariq Ali, and items had been thrown at orchestra members as they tried to enter. Inside, before the concert started, there were shouts of protest, some of which persisted during the opening bars of the Dvorak. They were eventually hushed by the vast majority who wanted to listen to the music, and then by the music itself which steadfastly emerged from the surrounding chaos. Rostropovitch, himself no lover of the Soviet regime and himself a lover of Prague — he had met his wife there — was at times seen to be in tears. He gave a most impassioned and heartfelt performance, clearly indicating whose side he was on. When he stood up at the end to acknowledge the tremendous applause, he waved Dvorak’s score in the air.

To my great satisfaction, when my daughter received her degree from Goldsmiths College, London, it was Rostropovitch who handed her the certificate.

One of Rostropovitch’s recordings of the Dvorak Cello Concerto

All that seems a long time ago now. I realise that many of the musicians I have mentioned are now dead, including Rostropovitch. Even in these uncertain times, however, the Proms have found a way to continue, though not without controversy. The Last Night will not proceed as it has traditionally done, with its rowdy, jingoistic, flag-waving celebrations. There will be no audience for a start so it is difficult to see how it could. The BBC management has decided to perform purely orchestral versions of the patriotic songs, ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘Land of Hope and Glory’, much to the disgruntlement of traditionalists, including Boris Johnson, who laments the ‘wetness’ of this decision and ‘our cringing embarrassment about our history.’ (* See, however, note at end!!)

The trouble is that a clear-eyed appraisal of our history reveals much to be embarrassed about. Thomas Arne composed ‘Rule Britannia’ in 1740 as part of a masque, ‘Alfred’, a heavily mythologised celebration of Britain’s past. The words were written by the Scots poet, James Thomson, whose mission was to bolster a sense of national pride in our Britishness. It was sung seventy-five years ago when the Japanese surrendered, reeling from the devastation of two atomic bombs. As for the words, as someone commented recently, it’s OK for Britons never to be slaves but it doesn’t matter if others are.

Thomas Augustine Arne (1710-1778)

The lyrics which Elgar set to music as ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ were written by A C Benson, who was inspired by the publication of the will of Cecil Rhodes, the mining magnate and proud governor of Cape Colony. The British South Africa Company named Rhodesia after him.. He left his considerable wealth for ‘the extension of British rule throughout the world’. His statue, along with those of other former slave owners and colonialists, is under threat of removal.

To be truthful, I rarely watch the Last Night of the Proms, ‘cringing’, in the Prime Minister’s words, with ‘embarrassment’ at all those swaying Union Jacks and party poppers and balloons. I know at one level it’s all just a bit of fun, but I honestly can’t see how anyone today can bellow out ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘Land of Hope and Glory’ without a deep sense of irony. The occasion has been unravelling for a few years now, anyway, especially during the Brexit debate (remember?) when the gold-starred blue flag of the EU was regularly waved among the Union Jacks. Those songs are not sung in the Proms in the Park in either Scotland or Northern Ireland. From 2002-7 when the American conductor, Leonard Slatkin was in charge of the BBCSO, he felt the flag waving element should be reduced and ‘Rule Britannia’ was included only as part of Henry Wood’s ‘Fantasia on British Sea Songs.’ On the Last Night in 2001, only a few days after the attack on the World Trade Centre, the traditional songs were replaced by a more sombre, elegiac programme. So the tradition has been open to modification before.

Yet it seems that tradition hangs on more desperately the more it is threatened. We cling onto it simply because it is tradition, not for any real belief in what it represents. Chi-chi Nwanoku, double-bass player and founder of the Chineke! Orchestra, has said that those patriotic songs ‘have been irrelevant for generations’. The young Finnish woman who is to conduct this year’s Last Night, Dalia Stasevska, dared to suggest it might be time for a change and was rudely trolled on social media for it. Surely, in these days of strident international discord, of racial disharmony, of the prospect post-Brexit of Britannia not so much ruling the waves as sinking beneath them, let alone living through a global pandemic, we should seize the opportunity the empty Royal Albert Hall has given us to reconsider the purpose and the content of the Last Night of the Proms. Nobody has put it better than the music critic, Richard Morrison: ‘There will never be a better moment to drop that toe-curling, embarrassing, anachronistic farrago of nationalistic songs.’

As I edit this blog before posting, it appears that the BBC will now present sung versions of ‘Rule Britannia’ and ‘Land of Hope and Glory’, much to the delight of the general public, if letters to the papers and tweets on social media are to be believed. I think it represents a missed opportunity, a weak-kneed caving-in to mindless populism. The songs are to be sung by a select group from the BBC Singers. I wish them well and hope they can keep a straight face.

Henry Wood, conductor of the Proms for half a century.