Desert Island Discs

One morning not long ago I left the radio on longer than usual and heard the familiar theme tune of Desert Island Discs. I haven’t listened to it for decades but it was a family favourite when I was growing up, along with The Archers and Journey Into Space.. The programme started five years before I was born and may well be going strong long after my demise. What I inadvertently tuned into was a special ‘lockdown’ edition playing a selection from a poll of listeners’ choices. Not a bad idea, but when the first ‘favourite’ was yet another rendition of Amazing Grace I switched off. It did, though, occur to me that a desert island might be the best place to be with the rest of the globe in the throes of a pandemic.

Like many people, I assume, I have often amused myself trying to select those magical eight discs. Why eight, I grumble, when the task quickly proves futile. But, of course, eighteen or eighty wouldn’t be enough. Music is a constant companion in my world; when I’m working or idling it’s always on, and I have getting on for a thousand CDs to keep me going, scores of which I’d count as my favourites.

Anyway, for the fun of it, here goes! The first three on my list are pretty well nailed in, and if you have read my earlier blog, Preludes and Fugues, you will know of them. When I go into my ‘room’ in the morning to paint or write, I put on some Bach. His reassuring sanity gets me under way. I am, in my son James’s brilliant word, a ‘bachoholic’. It is his keyboard music I turn to most, the ‘48’, the English Suites, the Partitas. But my first choice has to be the Goldberg Variations. From the simple, limpid opening aria, we are led through an array of thirty variations expressive of so many moods and emotions — the light-hearted and the serious, the playful and the grave, the wistful and the dance. Then, at the end, the aria returns like a homecoming, the same but somehow different.

It was written for the harpsichord, of course, indeed for a young musician, Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, but nowadays it is usually played on the piano. To perform it I would choose Andras Schiff, who captures these shifts of form and feeling with wondrously deft, fleet fingerwork. The highlights, for me, of the last two Proms seasons were his late night performances of the two books of The Well Tempered Clavier, the pianist alone with his instrument on a vast stage playing to a rapt Albert Hall audience.

I was not there in person, unfortunately, but I did go to a lunchtime Bach recital in Wakefield Cathedral some time in the misty past….

Lunchtime and Bach,

when to enter the cathedral alone

or with a friend on your arm

is to begin the search again.

You lean forward intent

as the scurrying scales and deft arpeggios

entwine the mote-dusted air…

you settle cross-legged perhaps,

your eyes scanning the tracery.

Loose confederacy of souls

seeking as the music seeks and probes —

that question answered….

the yearned for reconciling….

a severed thread reknit….

the taking at last of another hint.

And always, always,

the staying of oblivion —

bound as you are for this spell

by her flickering fingers which

flower preludes and fugues,

cadences breathing into the stones like prayer,

blooming out touching you.

Johann Sebastian Bach 1685 - 1750

*

I would, of course, have to take some Beethoven. If pressed, I’d have to say he is my favourite composer. The inexhaustible energy and invention of his music excites me every time I hear it. My desert island choice would not be one of his symphonies or concertos, great though they are, but one of his string quartets. The thirty-two piano sonatas and sixteen quartets contain his finest music, I think. Forced to choose, it would be the Quartet in C sharp minor op.131. The late quartets are wonders and not without strangenesses…..both in structure and musical content they push the boundaries of convention until, in this one, we arrive at a piece in seven movements which include an opening fugue of solemn beauty, skittering scherzos, a central theme and variations and fleeting transitional passages, with a rollicking finale. Beethoven intended the movements to be played without a break, another departure from normal practice. It doesn’t matter how many times I listen to this music, I always feel there is something about it I haven’t grasped. I got to know the string quartets in recordings by the Alban Berg Quartet and it is their performance I would choose.

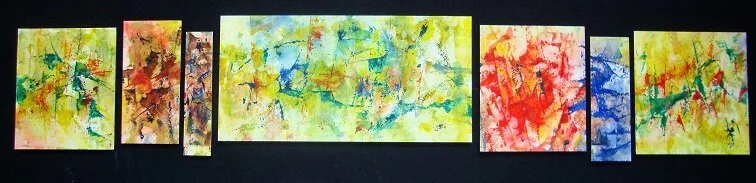

I make no apology for re-posting my own visual interpretation of the C sharp minor Quartet…..

The seven-movement Quartet in C sharp minor by Beethoven

Ludwig van Beethoven 1770 - 1827

*

You may or may not remember my reference to Schubert’s String Quintet in C major in a previous blog. This piece was my awakening to chamber music, almost literally, for I first heard it half asleep whilst ill in bed as a teenager. It remains one of my favourites and it would be my third choice. For me at least, every part of it hits an emotional spot. There is a symbiotic interplay between joy and melancholy which is captured in some way in each of its four movements. The music is like a landscape under shifting patterns of sunlight and shadow. The second movement is particularly beautiful, especially in the recording I would take. It was made at the 1952 Prades Festival by five of the finest string players of the time: Isaac Stern and Alexander Schneider, violins, Milton Katims, viola, and on the cellos, Pablo Casals and Paul Tortellier. I had an LP of it once but ,alas, no longer, and it doesn’t seem to be available on CD. But it lives in my mind as a wonderful example of devoted music-making which catches the feeling of the work at every turn, as if by instinct.

Franz Schubert 1797 - 1828

*

It is about time I had some orchestral music, and here —unbelievably reluctantly — I skip over the great Romantic symphonists of the 19th Century — Schumann, Brahms, Bruckner, Tchaikovsky, Dvorak — to land in Helsinki, the year 1907. This was when Gustav Mahler, on a conducting tour, met Jean Sibelius and discussed the essence of the symphony, just the thing for an afternoon stroll. They apparently got on well, but their views could not have been more divergent. Sibelius was intent on the structure of the symphony, its ‘severity of form’, its ‘profound logic’. Mahler, on the other hand, thought that ‘the symphony must be like the world….It must embrace everything!’ And as far as form was concerned he went for a sort of evolutionary principle. ‘The constantly new and changing content determines its own form’, he declared. Mahler had already written his Third Symphony — it was performed in 1903 — while it was to be another seventeen years before Sibelius’s Seventh saw the light of day, but I pick these two works as my fourth and fifth choices because they represent the polar opposites of what a symphony can be. Also, because I love them both. Mahler’s Third is enormous, an hour and threequarters of fantastic music spread over six movements. In Sibelius’s Seventh, the whole structure is concentrated into a single span lasting a mere 20 minutes.

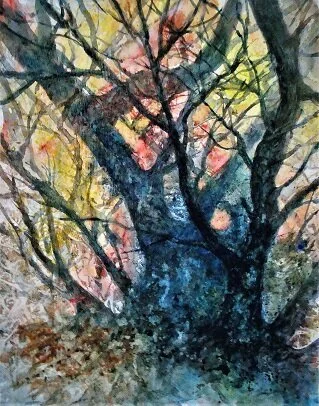

The Wildwood

Mahler was already thinking of the symphony embracing the whole world when he was writing the Third Symphony in 1895 - 6. ‘In it the whole of nature finds a voice’, he wrote. A native of Bohemia, he was brought up within earshot of barracks where he would hear the military bands practising. He absorbed the local strains of gypsy fiddle music and rustic dances. All around him he responded to the sounds of nature. All these influences found their way into his symphony: the fanfare which kicks it off and the marches which keep reappearing, the plaintive waltz-like tune of the second movement reminiscent of the landler, a local dance, the bird songs, pipings and rustlings which provide a sound backdrop to the whole work. And this is not to mention the voices — many would argue that Mahler was essentially a composer of song. The fourth movement is a song for contralto, a mysterious appeal to man to awake from slumber, based on words by Nietzsche, and it is followed by the raw tones of a boys’ choir, accompanied by bells. Mahler originally planned titles for the movements such as ‘Summer marches in….. Pan awakes…. What the Flowers tell me…’ He dropped the idea, perhaps for the best. Better to set aside a couple of hours and let your imagination do the rest.

What about the performance? Well, this will come as a surprise, as indeed, it was to me when I first came across it. There are many fine recordings by great Mahler ‘experts’ : Haitink, Abbado, Bernstein, for example. But when I was browsing in a record shop in Edinburgh (remember?) I came across a CD of a recording dating back to 1947, the year I was born. It was broadcast from the BBC’s Maida Vale studios, the BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Sir Adrian Boult. The soloist was none other than Kathleen Ferrier. The performance would have been lost in the ether had it not been for the attentions of one, Edward Agate, who recorded the broadcast from his radio onto acetate discs. These eventually found their way to Music Preserved who lovingly restored them to CD on the Testament label. It was a wonderful find and I treasure it.

Sir Adrian Cedric Boult with his long, whippy baton

This is a recording made shortly after the war when orchestras were depleted and performing facilities less than ideal. Mahler symphonies were still pretty much an unknown quantity, especially in Britain. The players were to perform a work they had never seen before. By modern standards the sound is decidedly ropey, lots of hissing and crackling and there are some rough edges to the playing. However, the more I listened to it the more I was gripped by Boult’s conviction and his assured, unaffected direction which keeps this gargantuan work on the move and holds it together. The entry of Kathleen Ferrier in the fourth movement is a huge bonus, of course, and her singing is a thing of great beauty: ‘O Mensch!…..Oh man! Pay heed! What says the deep midnight?’ And Boult’s pacing in the huge final slow movement and the building up to that brass-laden blast of affirmation at the end is magnificent. Given a practised orchestra and modern sound, this recording would be up there with the best. I often wonder why in his later career Boult did not record more Mahler.

*

Earthlight

While Mahler was busy embracing the whole world, Sibelius was moving in the opposite direction, looking to refine the ‘profound logic’ of symphonic form. After the relative expansiveness and romanticism of the first two symphonies, the succeeding works became sparer, more succinct, and more oblique in their emotional landscape — the enigmatically dark undertones of the Fourth, for example. By the time he got to his last, the Seventh Symphony, he reached the logical endgame, the synthesis of the musical material into a single, concentrated structure. Four ‘movements’ can be identified within the piece but each emerges organically out of the other without any break. The symphony moves inexorably to its climax, the layers of orchestral sound grinding like tectonic plates till the final C major chord, the B hanging in there till the last second, when it is resolved…or swallowed up: take your pick. An astonishing work.

As for the performance, there are fine recordings by Karajan, Colin Davis (his earlier one with the Boston Symphony Orchestra) and the Finn, Osmo Vanska, but I would take Sir John Barbirolli’s 1966 disc with the Halle Orchestra at its best. He captures the granite grandeur of the piece better than anyone.

Jean Sibelius (1865 - 1957) and Gustav Mahler (1850 - 1911)

*

Well, five down and three to go. I could fill those places many times over from the endless ranges of classical music, but I need to make room for one or two other musical inclinations.

It may amuse you to know that I once sang in a folk group. We entertained ourselves in the college bar and sometimes sang, if not for cash, at least for beer in one or two clubs and pubs in the Barnsley area. Oh, the recklessness of youth! One winter’s evening we sang in a country pub perched on a hilltop on the outskirts of the town. At the time I owned a Morris Minor with a retractable roof. It was my responsibility to drive to our destination with the rest of the group somehow squeezed into the modest seating. When, several hours later, we had sung and drunk our fill, we emerged blinking into a strangely white night. It had been snowing heavily whilst we had been carolling in the smoky warmth of the pub. I realised it was also my responsibility to get us all back to our lodgings. But responsibility was not high on our agenda in those days. And this was before the days of drink-driving rules and seatbelts. We all piled into the long-suffering Morris, opened up the soft roof and set off. I still don’t understand how I managed it without ending up in a ditch, but, full of beer and still warbling away to the cold night sky, we slipped and slid, swerved and veered down the narrow country lanes and eventually made it home in the early hours.

We modelled ourselves on such folk groups as the Yorkshire based Watersons, who were instrumental in the folk song revival of the mid-sixties. Much of their repertoire derived from rustic ballads collected by an earlier generation of folk enthusiasts such as Cecil Sharp and Ralph Vaughan Williams A singer who collaborated with the Watersons was Martin Carthy. I once had the good fortune to hear him in the upstairs room of a pub in Lewes when I was staying with a friend in Sussex. My sixth choice would be something from his album, ‘Crown of Horn’, ‘The Bedmaking’, perhaps. I love the keen edge of his voice and the percussive guitar playing, something I could sing along to whilst capering around on the beach of my desert island.

Martin Carthy

*

I must confess to a frightening ignorance of current pop music. That I still count Dire Straits as my favourite band is sad testimony to that. Though they broke up long ago, Mark Knopfler still turns out solo albums and if I had room I would take one of his songs, but I am elbowing him out to include something by Laura Marling. My son, James, introduced her to me a while back and I have taken a fancy to her…..in a musical sense, of course. She’s a contemporary singer-songwriter with a distinctive style. Her lyrics are often intimate, sometimes painfully so. She is an excellent guitarist too, and so far has seven albums to her name. The latest, ‘A Song for Our Daughter’, was released earlier this year to download, but is not yet available on CD. However, to my great surprise and delight, my daughter, Kate, bought me a ‘ticket’ for a virtual concert beamed from the empty Union Chapel where she promoted songs from the album. She performs with a still focus and intensity without the need to gyrate or dance around. This I like, and I couldn’t agree less with a reviewer by the name of Liz Thomson who found the concert ‘bloodless and boring’. ‘There was no word of greeting’, she opined, ‘not even much of a smile.’ She should have been more ‘intimate and chatty’, apparently. Why? What would it have added? Andras Schiff, when he performed Bach in the Royal Albert Hall didn’t feel the need to chat to the audience, even though they were actually present! Like him, Ms. Marling let the music speak for itself, which all good music does. As my seventh choice, then, I would take ‘You Know’, from her fourth album, ‘Once I was an Eagle’.

Laura Marling

*

And so to my last desert island disc. It arises out of my Sunday morning listening habits, when normal broadcasting seems to go awol. Radio 3 insists on playing ‘music to put a smile on your face’. I admit that I’m not much good with ‘jolly’ music. But at least it’s more bearable than Radio 4’s offering at this time, which is ‘Sunday Worship’. Nothing is more enervating than those pious priestly intonations and the dull four-square plod of English hymn singing.

And so I seek release in the music of India, the ragas, tunes which developed over two millennia from ancient folk music. A raga can be sung or played on any sort of instrument but it is normally performed on the sitar, often accompanied by the tabla, a pair of drums. It is music of great rhythmic complexity and is a fusion of improvisation and intense discipline. The particular selection of notes for each raga is centred on an emotion of some kind and a certain time of day. Therefore it is appropriate that, when I turn off the radio on Sunday, I listen to a morning raga, in this case ‘Raga Bilas-Khani Todi’, my final choice. It is played by Baluji Shrivastav on the surbahar, a low-pitched sitar. It is to be played two hours after sunrise. ‘Music is the root of joy’, said an ancient Sanskrit scholar. I agree.

Baluji Shrivastav

*

Those are my Desert Island Discs. You may even be tempted to try one or two of them, but I am aware that other people’s likes and dislikes often leave you scratching your head. I am also aware that the job is not yet done. What about the book and the luxury I am allowed to take? That will have to wait for another time.

Meanwhile, I will sit on the beach and meditate to my morning raga, not really minding whether I get rescued or not.

Mmmm. Not bad, this desert island.