A Sense of Place (2)

It is time to turn and go, to take the way back, and, as with most walks, to end where I began. For a moment I am beset with a strange restlessness, caught between the need to escape and the wish to return. But then I remember that it is not the destination that counts but the journey. An anecdote: a novice was out walking with his mentor, a Buddhist monk. There was little talk, just the walking. After a while the novice asked impatiently, ‘Where exactly are we going?’ The monk replied, ‘Here.’

The Shining Grass, watercolour

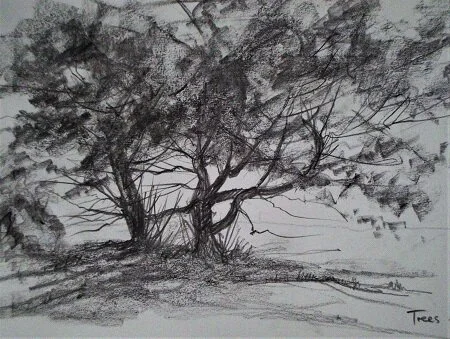

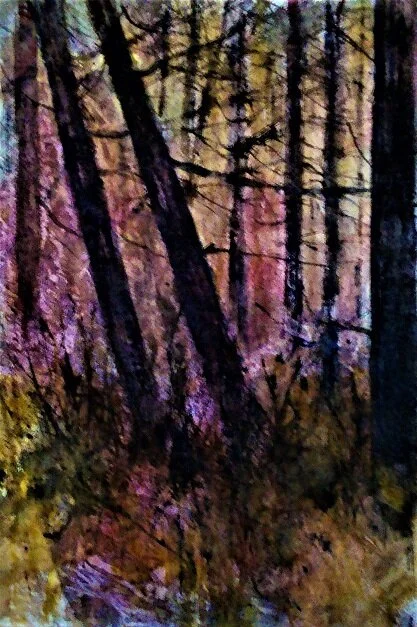

And ‘here’, through the shining waves of marram grass, is a grove of old pines, some stunted and wrung into twisted shapes. It is a mysterious place. I like drawing these trees.

I become aware of another sense of place, beyond its location on a map or the depths of its evolution through time. It is like a sixth sense, a feeling of attachment or belonging, that there is something going on here between the place and me. At home I have shelves of books on how to identify things — birds, butterflies, trees, rocks, shells — books of great fascination to me for the wealth of information they impart. But I can never find a page that tells me why I am so fascinated. I can tell what sort of trees they are, I have studied the cones and know how they reproduce….indeed, I have seen in Spring clouds of their pollen drift by on the breeze. But why was I strangely moved by the sight? What is that connection which sets off little sparks of insight, understanding, even emotion in me when I stand in this shadowy grove, that alchemical interplay between the observed and the observer?

Old Pines, an acrylic painting

*

Perhaps the lichen is the answer. Just about anywhere you look you can find lichens. They are commonest in the countryside where the air is clean but some hardy species can survive in grubby towns. Those patchy growths — grey, green, yellow, orange — some smooth, some crusty, some wispy or hairy: I see them everywhere on my walks, on stones, tree bark, rock, fence-posts, twigs. A lichen looks like a plant, but it isn’t. It is not a single, self-contained organism at all; it is part fungus, a tangle of threads or mycelia, and part alga, the blue-green strands spreading through the fungal growth. They feed and are fed upon by each other. Unable to exist independently, they live through a symbiosis of giving and taking, a to-and-fro of moisture and nutrient which makes the lichen possible. I like to think that it resembles the interconnection between the dynamic energy of the evolving world of nature and the creative energy of the human imagination which perceives and responds to it. Unfortunately, my thought is the stuff of whimsy, the flaw being that while I may need the pine grove to arouse in me feelings of mystery, I cannot conceive of any way in which the pine grove needs me. As with hugging trees, I may get some pleasure — a perverse one, some might say — from hugging the tree, but I’m sure the tree is indifferent to my embrace.

Still, it was worth a try, and lichens remain extraordinary organisms and there must be a message in them somewhere for us human beings.

*

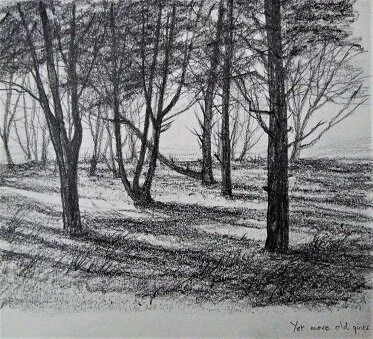

Standing among these old pine trees I cannot understand the mystery, because I am part of the mystery. With a wry nod in their direction I step out into the sunlight and find the path along the shore, this time the shore of the Tyne Estuary where the river sweeps round in a wide arc to merge with the Firth of Forth. I look across the broad flats of sand and mud to the farther shore and its conifer plantations and, in between, the random scattering of boulders which lie in the water on a plane of flat rock below. With the light behind them they appear like petrified Morse Code.

Rocks in the Estuary, a pencil drawing

And there, licking out into the estuary, is Sandy Hirst, a long spit of shingle sitting atop the underlying bedrock, stretched and moulded by the incoming tides and currents.

Sandy Hirst, a mixed-media picture

Here is another example of the provisional nature of evolution and consequently of life, including my own little one. Those boulders once belonged in the rocky hills to the south but have been borne down by huge creeping glaciers to end up here perched like loose teeth in the estuary, while the spit of Sandy Hirst is, geologically speaking, very young and is constantly on the move, shifting gradually south-westwards.

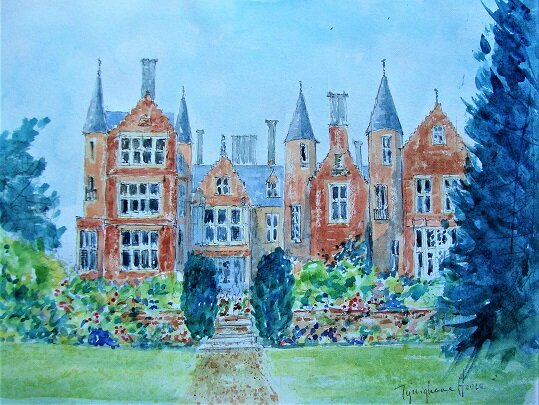

As indeed am I, now probing through the woodland of Tyninghame Links which surrounds the policies of Tyninghame House. A broad avenue of beech trees leads from the wood up to the house. Suddenly I am surprised by the thud of hooves and two ladies ride up on horseback. At the sight of me they slow down, saddles creaking beneath their jodhpured bottoms. I step aside and bid them good morning, ‘or is it afternoon?’ I resist tugging my forelock. They look down at me and pass by without reply. Perhaps I shouldn’t be here.

*

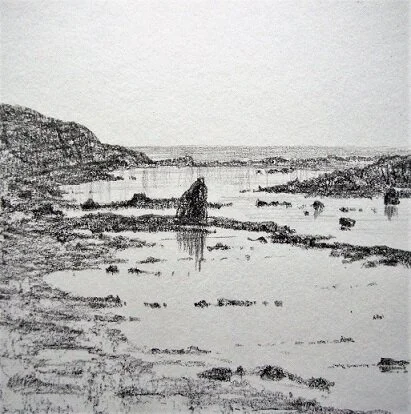

For centuries this was the domain of the Earls of Haddington. However, the house was sold in 1987 and is now a set of luxury apartments going for around a million pounds each. Glimpsed from the road or through the odd break in the woods it appears like a fairy-tale castle with its red sandstone walls, its turrets, spires and crenellations. There is evidence in the stonework of a medieval tower house, but the present building was designed in the 1820’s by William Burns in what was known as the ‘baronial’ style, a sentimental harking back to a romanticised version of the Middle Ages.

Tyninghame House, a watercolour painting

Once a year the public are allowed in, for a small fee, to view the gardens. There is the Walled Garden with its arboretum and statues of Bacchus and Diana and their fruit and lyre bearing minions posing in the niches of the yew hedge, the Secret Garden and the contrived randomness of its billowing herbaceous borders, and the comically named Wilderness, with its fine specimen trees and closely cut grass pathways. To the south of the house, beyond the ha-ha — the carefully concealed ditch to keep cattle and deer at a picturesque distance from the gardens — stand the ruins of a 12th century church, known inevitably as St. Baldred’s, though if indeed he did have a structure here it would have been a much simpler affair and four centuries earlier. There remain two fine Norman arches with dogtooth ornamentation and the grave monuments to several deceased Haddingtons.

And so we walk up and down the shady walks, take photos and catch scraps of conversations drifting by on the breeze like expensive scent, then have tea and home-made cakes under the trees.

*

But that was another time, that visit to the manicured lawns and flower-beds of Arcadia, another place in the mind, where nature is managed to create order out of chaos, beauty and delight out of the real wilderness.

The notion of an ‘ideal’ landscape goes back to the mythologising of the region of Arcadia in Grecian Pelopponese. The name comes from the legendary hunter-king, Arcas, and it was here that Pan, the god of wine and other pleasures, was supposed to dwell. Interestingly, geology helped produce the myth. Arcadia is mountainous and aeons ago was the site of vigorous tectonic activity which riddled the limestone rock with cracks and chasms to produce subterranean channels and waterways into which all the rain drained. Consequently, the only thing the land was fit for was herding sheep and cattle. In classical times it came to represent an idyllic pastoral landscape of rustic simplicity where shepherds lolled beneath the olive trees playing their pan-pipes while nymphs flitted and flirted among the foliage. Virgil set his pastoral poem, the ‘Eclogues’, in Arcadia, and subsequently the place was depicted in art and literature as a vision of the simple, pure life lived in harmony with nature.

Henryk Siemiradski (1843-1902), a Polish artist, from the exhibition, ‘Searching for Arcadia’

Like so many 18th and 19th Century estates, the grounds of Tyninghame House are an attempt to create a version of Arcadia, its own distinct sense of place. It is an illusion, a pleasant one, which rests on the amusing paradox that, though the landscape is presented as entirely ‘natural’, even ‘wild’, it is carefully, artfully, crafted by man and celebrated by artists and poets to convey a kind of dreamlike beauty which unites nature with order and proportion. There is a managed spontaneity in which we can experience the frisson of being in nature, yet feel safely, comfortably at home. It is an illusion to which we readily succumb in our search for the chosen spot, that perfect setting for the play of our feelings and the yearnings of the imagination. It is a place which, the more we seek it, the more it eludes us.

Paradise

Given the earthly paradise —

the garden, for example,

the way you’d recline under that aspen,

your cheek fanned by zephyrs while nymphs

or lambs were frolicking

and your companion breathed his reed —

given all that air, those airs,

what would you then do?

Sometimes out walking

I’ve spotted places I’d have

as corners of my paradise —

tree-badged limestone outcrops,

verdant recesses in forests and, once,

a pool of emerald water overhung

with rosehips where I sat down

to really take it in.

But really I was taken in.

The damp ground, the breezes chill,

midges in abundance and,

to be truthful, I was alone, my mind

tuned only to where I should be heading —

the car parked in the distant village,

and home, with me in an armchair

dreaming of paradise.

A sense of place is in the end a malleable term which can mean what you want it to. It will resonate in different ways for a naturalist or ecologist, for a painter or poet, and for a casual tripper who might simply sit on a folding chair and drink tea in the gardens of a country house.

*

As the haughty ladies disappear down the grassy ride on their trotting mounts, I leave Links Wood and return by the still empty car park to find the quiet woodland path I started out on. I reflect that it was an earlier Earl of Haddington, the 6th, who laid out the fields and plantations I have come to regard as ‘my’ patch. Of course, it is no more mine than anybody else’s, except in one sense — it cannot ‘mean’ the same to anyone else as it does to me. It is mine in a psychological sense, much of which lies deep in the subconscious. My ‘sense of place’ is a private idea, with any luck an enriching one, through which I can penetrate the landscape both with my walking boots and with my senses alert, my thoughts at the ready. I emerge from the overgrown path to end, of course, where I began, yet the view is somehow different.

The Leaf

There is a place where

track and hedgerow

tree and sky

meet

where the air sharpens

and light springs

begetting more light.

Crouching in the dark hold

of his memory he fingers

the golden leaf

picked from the wayside,

pocketed for later identification.

Deep Wood