Desert Island Discs (2)

A couple of weeks ago I left you with my eight desert island discs having been prompted by a chance hearing of the venerable programme to attempt again the impossible choice. It could well be a different selection today. Be that as it may, I realise that the task is not yet done. At the end of the programme the guest is required to choose a book and a luxury to take to his island solitude.

Somewhat to my surprise I find that they still offer you a complimentary copy of the Bible and Shakespeare — but it is the BBC, I suppose. I do recall an edition once where the guest turned down the offer of the Bible, a brave move. I would do the same. I can’t think of a book I’d be less likely to read on a desert island — last year’s telephone directory, perhaps. If I were allowed a substitute for the Holy Book, I would take a little volume I came across in one of those cut-price shops in the high street (remember when you could enter a bookshop and browse without having to put everything back on the quarantine shelf?) which sold cheap art equipment, children’s toys, jigsaw puzzles and a multitude of bargain books: romantic novels, war stories and stacks of books on cooking and gardening. And, of course, the ever burgeoning displays of ‘self-help’ manuals. I was poking around these shelves pretty aimlessly — it was a time, without going into detail, I felt I needed a bit of self-help — and there, tucked unobtrusively between Yoga in 10 Minutes and Detox your Brain, was a modest, buff-coloured paperback called The Daily Stoic. I had read a bit about the Stoics — indeed, I still had a copy of Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations on my shelves which I had skimmed through all too superficially.

I flicked through the book, made a few internal nods of approval, and bought it. It is one of those books which is helpfully arranged according to the calendar, a page per day. Each day starts with a brief quotation from a worthy old Stoic, almost always Epictetus, Seneca or Marcus Aurelius. For example, Epictetus might say, ‘Don’t abandon your pursuits because you despair of ever perfecting them.’ There then follows a commentary putting the saying into some sort of context: mention of the ‘cognitive distortions’ psychologists speak of, ‘all-or-nothing thinking’, and how perfectionism rarely begets perfection, only disappointment. Anyway, I read my daily page for a year and then started again, this time briefly noting the contents in a little black notebook. When the third year began I put the original book back on the shelf and simply read from my notebook. This I still do.

Epictetus 50 - 135AD and, below, Marcus Aurelius 121 - 180AD and Seneca 4BC - 65AD. I have a feeling they would have relished the challenge of ‘lockdown’.

What I like about these slightly cranky old Stoics is that theirs is a very pragmatic philosophy. It does not rely on myth or superstition. God, or the gods, are hovering around in the background from time to time, but they never seem to do anything. It is more to do with how to cope with daily living: to be aware of our emotions, for example, but not get too carried away by them, to be adaptable to circumstances and not to worry about things we can do nothing about. The common conception of Stoicism as a dour, killjoy sort of philosophy is wide of the mark. In my reading of it, at least, it celebrates happiness and freedom — eudaimonia — but we often mess it up with self-delusion, overindulgence and fear. For the Stoics, our most precious possession is our mind, our ability to choose. ‘Who is invincible?’ cries Epictetus. ‘The one who cannot be upset by any thing beyond his own reasoned choice!’

Hinges

Strangely enough, I found this outlook reflected in the psychological practice of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy. I have submitted only once to such counselling, at a time when I was experiencing extreme anxiety, often about ridiculously trivial things — a bit of rain seeping through the window, an odd squeak in the car. I had had a bout of this sort of thing a few years before, but my doctor told me it was just the result of living in the twenty-first century and packed me off with some pills. But this time, my therapist, though he had an unnervingly beady eye with which he fixed me throughout the session, did at least enlighten me on the part played by my own obsessive, catastrophising mind in my feelings of anxiety. Stuff happens, it always will, but the cause of my anxiety was not the events themselves but the way my mind reacted to them. As for the rain seeping in, he advised me the next time there was a storm to fling the window wide open and let it sweep in. ‘Bring it on!’ he said. Luckily, I am still waiting for such a storm to arrive.

There is also a perhaps unlikely link between Stoicism and Buddhism, at the heart of which is the notion that suffering is caused by desire, our cravings, longings and loathings which can never be satisfied. Epictetus, alarmingly, declares that you can only satisfy desire by defeating desire itself! Unfortunately, I am quite prone to desire and pretty hopeless at coping with the dilemmas of life Stoicism addresses. Luckily, they were quite happy for you to keep on trying. ‘It’s continually in your power,’ says Marcus Aurelius, ‘to reignite your principles. It’s possible to start living again!’ Or, as Winnie-the-Pooh says, ‘I always get to where I’m going by walking away from where I’ve been.’ Someone asked me once, ‘Are you a Stoic, then?’ I said, ‘No. That’s why I read the Stoics.’

The Benefits of a Classical Education

*

Here’s a poem. I’ve developed a metaphor for all this ‘living’ business. It’s to do with windsurfing. I once had a go at this and achieved a paltry level of competence. I was OK on the calm waters of the local water-park but when I tried it in the sea in Spain I spent most of my time climbing back on my board. But I got the principle that it was about keeping a balance between the natural forces of wind and wave and the way you angle the sail. Too much of one or the other and you end up in the water.

I wrote the poem after a visit to Sandal Castle in Wakefield. Its ruins stand on a hill overlooking the lake, an old gravel pit, where I used to windsurf. Standing on the old ‘motte’, I saw that I was eye-level with a kestrel — Gerard Manley Hopkins’s ‘windhover’ — and it became an image for that point of balance, that equilibrium which we seek but never attain.

From the castle turret you think

you could reach out and touch

his wing-tips but he keeps

you at arm’s length, the kestrel,

hooked blade of chestnut and blue-grey,

feathering the wind. It seems

you can look him in the eye

but his sights are set, lasering

the tussocky ditch below.

And while he’s anchored to his purpose

your gaze drifts off, sidetracked

by whatever takes you in.

A couple at the viewpoint

scrupulously held, primed

with intent, inches from a kiss.

On the perimeter path

that dog in mid-leap, jaws poised,

the flung ball quivering in its arc.

Two boys, angel arms spread wide,

teetering on the battlements,

laughter caught in a sudden gust.

You watch and weigh a world that seems

in ceaseless suspense, about to pounce,

impossible to grasp.

Then something turns your head again.

Where the kestrel was is the hole

he’s dropped through with a sidelong flick,

the air collapsed beneath him.

You blink at an absence, blinded

by the dazzle of the distant lake

the light leaps off like a skimmed slate.

Beyond you, out of reach, windsurfers

slice through the whipped waters,

braced against the taut sail,

arrowing between shores….

winging it, you wonder, just holding on?

*

I’m afraid to say, ashamed, even, as an ex-English teacher, that Shakespeare would have to go the same way as the Bible, overboard. It occurs to me that without these hefty tomes I’d stand a better chance of floating to safety on my raft anyway. Much though I acknowledge the Bard’s greatness, I’m pretty sure that much of his Complete Works would remain unread. I’d re-read King Lear. Having ‘done’ it for A level and later taught it many times to my own A level students, it’s in my blood. I still think it’s his greatest play for the extreme emotions it elicits and its extraordinary examination of human insanity.

What, then, would I take instead? I can’t think of a novel I’d want to read over and over again. The Collected Wordsworth crossed my mind. Those of you who have read my other blogs will know of my attachment to him, but, in truth, half (to be generous) of his output is uninspiring fare. I think Yeats wrote some of the finest poetry ever but there’s much I can’t get my head around. And Hopkins comes close — I love the alchemy of his language. But no, I’d have to dismiss these greats and in the end take the poems of Norman MacCaig. He was an Edinburgh man who spent much of his life as a primary school teacher. He also spent his holidays in the Assynt region of the Northwest Highlands, the inspiration for so much of his poetry. ‘Landscape and I get on together well,’ he said, and in poem after poem he evokes the sights and sounds of nature with brilliant yet unpretentious imagery. In July Evening he describes a bird singing in a reedbed as ‘a tiny silversmith / working late in the evening’, sees a cottage, ‘the rooftop / with a quill of smoke stuck in it’, a bee ‘feeling its drunken way / round the air’s invisible corners’. He is not merely a scene painter, though. He feels an almost metaphysical connection to nature. In Wordsworth’s phrase, he sees into the life of things. He ends that poem thus:

Something has been completed

That everything is part of,

Something that will go on

Being completed forever.

I take his Selected Poems with me whenever I go travelling. Perhaps I could have an upgrade to his Collected ones as my constant companion on the desert island.

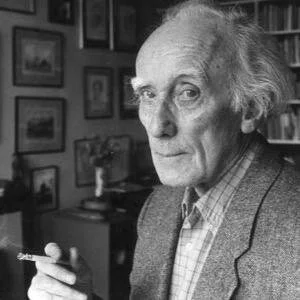

Norman MacCaig (1910 - 1996)

*

Now, if I’ve played my cards right and can count the Stoics and Norman MacCaig as substitutes for the Bible and Shakespeare, then I should still have one choice left!

As with the music, the choice is bewildering. Even though I had to downsize my book collection when I moved north, my bookshelves still surround me like geological strata, revealing the layered sediments of my past enthusiasms, many of which have weathered away leaving a few immovable outcrops like volcanic plugs. There’s a fat orange Penguin paperback of J.M.Roberts’ History of the World, ninety-nine per cent of which I have forgotten, which would keep me going for a while. And hidden away at the bottom of one bookcase is a signed copy of Bob Copper’s A Song for Every Season. He was from a long line of farmers and folk-singers dwelling in Sussex. It was at a regular folk-singing session in one of the wonderful pubs of the region that I got the book, a loving evocation of the rural life of his family as well as a compendium of folk songs. Perhaps I could sit on the beach and start retuning my rusty old voice to ditties such as ‘Shepherds Arise’, ‘The Lark in the Morning’ and ‘Good Ale, thou art my Darling’. Or perhaps not.

In the end, I am choosing a book by the inveterate naturalist and walker, Tristan Gooley, The Walker’s Guide to Outdoor Clues and Signs. It is packed with information about how we can ‘read’ nature by careful scrutiny of what we see in front of us — what I can learn from the shape of a tree or the way its roots grow, the different coloured bands of lichen on a sea rock, the way the leaves of the Prickly Lettuce align North-South when exposed to the sun. I would learn that ‘rainbows do not exist without observers’, get to grips with clouds and contrails, look up to the night sky — completely devoid, I would assume, of light pollution — and tell my Aquila from Cassiopeia, my Scorpius from Sirius, my Aquarius from Sagittarius.

The Reader

The Stoics and Norman MacCaig would feed my mind with philosophy and poetry. Mr. Gooley’s book would keep my senses alert as I wandered around my island and probe its secret corners. What else could I possibly want? I had almost forgotten — my luxury.

*

I suppose many people these days would take their smartphones to keep on twittering and facebooking and sending forth emojis from their lonely isolation. I think the selfies would soon wear thin, though — ‘Hi, this is me and another palm tree. Bye.’ Anyway, I haven’t got a smartphone.

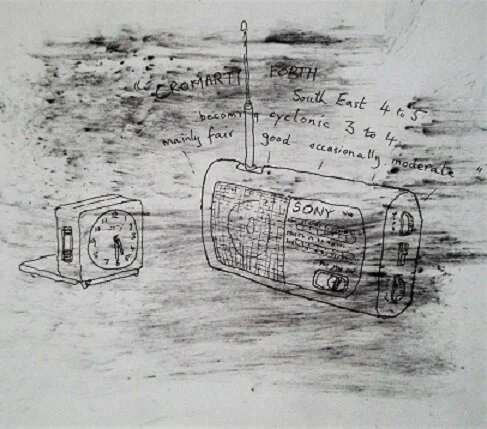

I did flirt with the idea of a box of good wine but the luxury would be short lived, I fear. My Stoicism would not extend to staring at an unopened bottle for too long. So, I would take, as some sort of link to the world beyond, my little transistor radio with a supply of AA batteries. I bought it in a Cash Converters in Wakefield many years ago. It cost £4. I take it whenever I go away. I take it camping and I take it to the beach on sunny days. The reason I bought it was because it has Long Wave which means that I can often get reception where even DAB fails. It also means that I can listen to the Shipping Forecast in the morning, that daily litany of wind direction and speed, visibility and atmospheric pressures proceeding steadfastly clockwise round the British Isles from Viking to Southeast Iceland. Living on the coast of the Firth, my ears prick up when it gets to ‘Forth’, and the Inshore Waters from ‘Rattray Head to Berwick-upon-Tweed — southerly or southeasterly 3 to 5 becoming cyclonic 3 or 4 later Thundery showers for a time Good occasionally moderate.’ There, what more do you need to know? The Shipping Forecast has been broadcast, with various adjustments along the way, for around a hundred years and it is a peculiarly British thing. Thousands of people listen to it who have never been to sea in their lives and haven’t a clue what it means, but somehow it’s become part of their identity. I think of a little scene in Barry Hines’ book, A Kestrel for a Knave, immortalised in Ken Loach’s film ‘Kes’. The teacher is reading out the register — another litany I am familiar with — and when he announces the name ‘Fisher’, a small voice pipes up, ‘German Bight’. It belongs to Billy Casper, a skinny, deprived boy and the butt of class jokes. He has been up since dawn delivering papers and clearly has the Shipping Forecast in his DNA. Charlotte Green, the Radio 4 announcer, said, ‘The Shipping forecast’s the nearest I ever come to reading poetry on air; the place names have their own special beauty and the forecast its own internal rhythms and cadences.’

*

Jim Maxwell, the revered Australian cricket commentator, cannot quite understand what the Shipping Forecast is all about and takes a gleeful delight in announcing, ‘And now Radio 4 listeners will be leaving us for (roll of drums) THE SHIPPING FORECAST!’ Which inevitably leads me to the other main reason I would want my transistor radio beside me: Test Match Special, another beloved and peculiarly English institution. I would hope, however, that it did not compete with the Shipping Forecast as it did in January, 2011, when England were playing Australia abroad and the match was approaching its nailbiting climax. Long Wave listeners back home were lying in bed as midnight approached when, as the Times reported, ’instead of hearing the sound of Australia’s no.11 Michael Beer’s stumps being splattered by England fast bowler, Chris Tremlett, those tuned into Radio 4 Long Wave were told that the Shetland Isles were expecting wintry showers and a westerly wind.’

Tracking back in time, TMS is inextricably associated in my mind with the likes of John Arlott, Jim Swanton, Brian Johnson, Christopher Martin-Jenkins and, more recently, Jonathan Agnew, Henry Blofeld and Simon Mann. Unlike the breathless pace of football commentaries, cricket, where for ninety-five per cent of the time nothing happens, allows the commentators and their summarisers time to analyse, describe the scenery, the pigeons, the buses going by, dwell on the game’s history and develop their own style of presenting, often with highly comical results. Who can forget ‘Johnners’ and ‘Aggers’ collapsing into uncontrollable giggling after a batsman, frantically trying to make his ground after a run, leapt rather unsuccessfully — and painfully — over the stumps? Jonathan Agnew’s comment, ‘Yes, he couldn’t quite get his leg over,’ started the whole thing off. And there is the constant ribbing by Agnew of his co-presenter, Geoffrey Boycott, a great but often frustratingly cautious batsman for Yorkshire and England. ‘I have an email here, Geoffrey,’ began Agnew, ‘from a man in Nottingham who says he was watching you bat at Trent Bridge and got so bored he fell asleep.’ ‘Ay,’ replied Geoffrey, ‘and I bet I were still battin’ when ‘e woke up.’

*

As for music, beyond my eight permitted discs, I don’t know what I’d do. Radio 3 might be beyond the reach of my little radio. Perhaps some tribal rhythms from the Antipodes would drift across the airwaves. More likely some fierce blast of gangsta rap would attach itself to a particularly strong frequency and assault my eardrums. Or maybe I would just find, like Caliban, that

‘the isle is full of noises,

Sounds and sweet airs that give delight and hurt not.

Sometimes a thousand twangling instruments

Will hum about mine ears….’

However, at least I could tune into the World Service News and hear how the civilised, or not so civilised, world is coping with race riots and pandemics, and reflect that I’m better off where I am.

‘As each day arises,’ says Seneca the Stoic, ‘welcome it as the very best day of all and make it your own possession. We must seize what flees.’