Traprain Law

I am starting out from the village along a narrow lane, a handful of stone cottages then open country. I don’t normally walk on roads but this is a very minor one — the odd tractor maybe. The land slopes away steeply to my right in waves of golden gorse, down to the valley where the Tyne ripples its way from the hills to the coast, the Firth, three miles or so downstream. I’ll be walking back along its banks in a couple of hours time.

But now I pass beneath the long span of a bridge which crosses the valley and carries the A1 above. It’s an elegant structure and slightly surrealistic in this pastoral setting. In one of the concrete spars is a door, presumably access for maintenance workers. It is open, daubed with rough graffiti, a litter of cans and spent vodka bottles spilling out. I imagine momentarily some derelict soul taking refuge there.

He did not walk by

but pushed at the timber,

heard the hinges whinge

and crossed the threshold.

He scarcely took in

the debris that snagged his feet,

the damp ashes, empty cans,

graffiti sprayed like curses.

His eyes scanned the concrete,

read his scratched initials,

then followed his breath

to the patch of blue and clouds, far off.

The bridge also provides shelter for a small flock of sheep munching on a scattering of turnips. They gaze at me passively as I carry on my way. Suddenly, a charm of goldfinches flickers across the lane and settles in the hawthorn blossom. It’s going to be that sort of day.

*

Before long I leave the lane and turn up a steep track — drystone wall, tree still leafless against the sky — to arrive at a farmstead.

Towards the farmstead. Something about that tree……

Some of the outbuildings have been converted into stylish homes, rural escapes, no doubt, for affluent city-dwellers. Glancing over the stone boundary wall I see two elderly ladies sitting in a small garden drinking tea. I follow the track round the back of the farm and join a path along a field edge.

The Farmstead

*

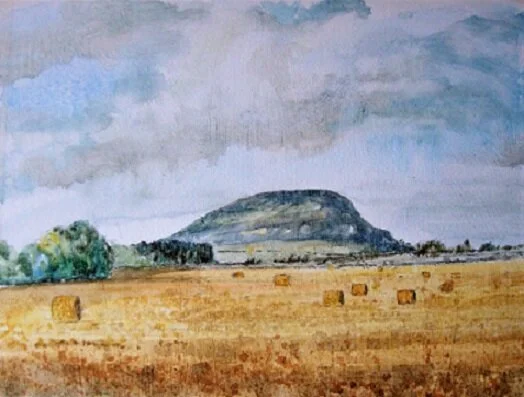

And there before me stands the focus of my walk…..

Traprain Law

The hill looks bigger than its 725’, thrust up as it is from the gently undulating landscape surrounding it. Geologically speaking it is a laccolith, its domelike hump heaved up by volcanic forces which stopped short of breaking through the surface. Its tough granitic rock stood fast while the softer layers around weathered away.

My path emerges onto a road which runs along the base of the hill. There I see a young woman nailing a notice to the stile I am about to cross. She is a ranger from the Countryside Dept. of the Council. The notice is to advise metal detectorists that their pursuit at this particular site is strictly illegal. She tells me that it is a hundred years since the spectacular discovery of a hoard of silver on the hilltop. The publicising of this anniversary has apparently tempted some treasure seekers to climb up and see if they can find some more. Holes have been dug, she tells me. I assure her that I intend no such mischief, I’m just going for a walk. I wish her good luck and cross the stile.

I know about the treasure though. An excavation in 1919 uncovered 53lb. of silver buried beneath the outline of an Iron Age hut. It is Roman silver. By the end of the second century the Romans were losing interest in the territory north of Hadrian’s Wall. There are few reminders of their presence in these parts. The dominant power at that time were the Votadini, a Celtic tribe who occupied Traprain Law, fortified it with ramparts and ditches and made it their capital. There is some debate about how the silver came to be here. The odd thing is that most of it was sliced up into little bits, maybe to be melted down and used as coinage or converted into torques and other valuables. It may have been plunder from a raid on the Romans further south, but the prevailing theory now is that it was some sort of tribute payment at a time when the Romans were in retreat to appease the Votadini and keep the peace among the other local tribes.

*

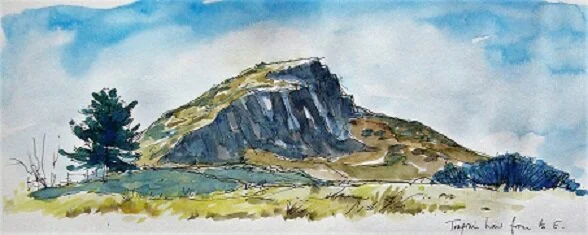

Anyone who approaches the hill from the North cannot fail to notice a huge chunk bitten out of its eastern end. Once safely over the stile I climb the steep path through trees up to the edge of the old quarry.

The path up from the road

In 1938 this end of the hill was leased to the Council for the extraction of rock to use as roadstone. An illuminating entry in Hansard for 1966 finds the good 12th Earl of Haddington petitioning from his seat in the House of Lords for a proposed extension of the lease to be refused, citing ‘the appalling disfigurement this quarry is causing to a very lovely landscape’.

The eastern end of Traprain Law and the quarry

The quarrying stopped. Now, scrub and young trees are beginning to soften the lower reaches but the upper faces remain stark and severe. There is a route up to the hill’s summit which clings somewhat perilously to the quarry edge. A sign, complete with an image of a falling man and tumbling boulders, warns me against attempting this route. I am one of those incomprehensible individuals who takes any sign forbidding me to do something as an invitation to go ahead and do it. Well, on this occasion I do not — but I do confess that once I did. The climb is extremely steep and the ground not too secure, but the day was dry, sunny and carefree so up I went. I recall that half way up I lay down and, shuffling to the edge of the quarry, looked dizzily down the long shafts of sliced rock vanishing beneath me, and watched the grey napes of the jackdaws as they circled below. I reached the top without mishap, but once was enough. I certainly wouldn’t come down that way.

So I cast a wry wink at the notice and take the path ahead, a delightful amble round the south side of the hill, the broad fields and treelines stretching away to the Lammermuirs in the distance.

Looking south from Traprain Law

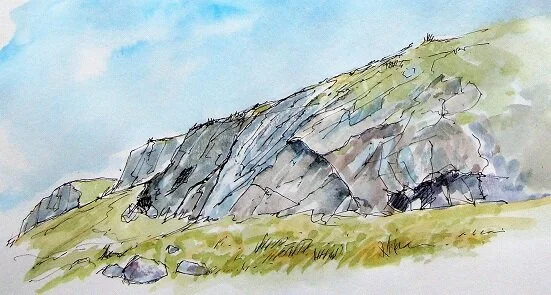

On this side of the hill sheer slabs of rock rise vertically towards the summit. It is a favourite haunt of climbers, and I have heard their faint calls blown by the wind as they inch their way up the crevices of the rock face.

The south side of Traprain Law

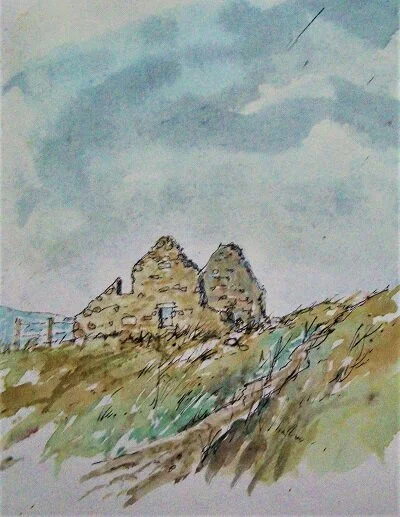

Today, however, the rock is empty, just air and light. My low-level path leads me round to the far end of the hill. I become aware that I am following hoofprints. They lead me to an open space with a ruined stone hut. It is roofless, but there are the remains of a fireplace — I wonder who once sat at this hearth, smoking a pipe, perhaps, and listening to the wind.

The ruin

It is from here that I leave the path and its gathering of hoofprints and strike upwards through tufty grass and rocky outcrops to the top of the hill. Half the Lothians are laid out below me. I can see how this would be a perfect place for a stronghold — a plateau broad enough to base a village, an ‘oppidum’, surrounded by ramparts and steep slopes, and panoramic views to spot any unwelcome incursions. The imprints of those ancient peoples can still be discerned: shadowy hut circles, patterns of stones. There were burials here in the Bronze Age.

These buried bones

nudging earthenware

prising roots apart

once leapt with marrow

levered loads

and danced in the wild hours

were felt in

when rain or death

was due

What those dimly imagined ancestors would not have witnessed is the bright triangulation pillar which marks the summit. Nor (but who knows?) the sight that greets me now: a herd of a dozen or so dark brown ponies clustered placidly around the trig point as if guarding it.

The Exmoor ponies on Traprain Law

These Exmoor ponies were introduced to graze the hill grasses and thus allow the flourishing of wild flowers, many of which would not survive in longer, damper grass. Wild thyme and harebells, primroses and ladies’ bedstraw — once stuffed in mattresses to sweeten the smell — all grow here. There is also a rare form of lichen with the wonderful name of peppered rock tripe to be found on the stones around the summit.

A few paces away I find the peculiar rock formation known as the Maiden Stone. Down the centre is a narrow crack and the myth goes that if you can pass through it you will live a healthy and fertile life. I ritually squeeze through and give thanks, though I’m not sure I need the ‘fertile’ bit now. Another legend of the Law is that Loth, a 6th century king — who gave his name to the Lothians — on learning that his daughter was pregnant from a surreptitious union with her cousin, strapped her to a chariot and drove her over the edge. Remarkably, she survived and escaped in a boat across the Firth to Fife where her son was born. He was St. Mungo, supposedly the founder of Glasgow.

The Maiden Stone

I leave the wraiths of history and legend behind, say a soft and foolish farewell to the ponies, who eye me strangely as I head off down the north side of the hill, the coastal plain parcelled out below me, North Berwick Law and Bass Rock protruding like the volcanoes they once were.

*

My way back takes me along farm tracks and hedgerows to a little settlement and the ruins of Hailes Castle, rising sheer from the banks of the River Tyne. The place is usually remembered as the place where Mary, Queen of Scots, stayed fleetingly before her ill-conceived marriage to James Hepburn, Earl of Bothwell. I have more fellow feeling, however, with the luckless George Wishart, an ex-teacher (like me) and Protestant reformer (unlike me). He was imprisoned here by Hepburn before being carted off to St. Andrews to be burnt at the stake as a heretic.

Hailes Castle

I leave the castle — it is well worth a detailed exploration, but today is not the day — and descend a stony track to the river. A long wooden footbridge takes me to the far bank where I join the riverside path back to the village. The way is wooded for much of its distance and with the river gliding by it breathes tranquillity. Today, the path and the woody recesses brim with primroses, wild garlic and banks of daffodils. I don’t have the good fortune to catch the azure flash of a kingfisher this time, but there are goosanders, a couple of stately swans and I spot a dipper perched on a rock.

The way back by the River Tyne

I pass under the A1 bridge again and my walk is almost done. I find a grassy perch on the river bank and sit for a while. The contingency of lived experience….that’s what I ponder. The landscape with figures I have wandered through — those ladies in a remote garden drinking tea, the earnest warden intent on keeping treasure-seekers at bay. And the ghosts — whoever hung out under the motorway bridge, the pickaxe clatter of the old quarrymen, the shepherd in his stone hut, the spirits of those who cooked and sang, buried silver and sharpened their weapons within the defences of Traprain Law. And those ponies…do they know more than we think? Is there a thread to weave it all together — the randomness and unpredictability with the sense that everything is somehow connected? Happily, these futile musings are interrupted by a movement on the opposite bank of the river. There, in a grassy clearing, standing perfectly still and looking directly at me, is the slim dark form of a deer, a roe deer. I sit motionless, savouring the pure present — perhaps this is the thread — before it inevitably turns to past. I would sit here all day, but the deer has had enough and disappears into the cover of trees.

*

Between the wind’s rumouring

and the chime of the harebell,

between the tightening night and the skin of ice,

the leaf loosened and the earth’s weeping,

between the lips of dawn

and the polyphony of light levelling

through the pine trees,

is the space to be sounded,

the pulse to be felt,

the breath to be caught.

I watch the moment escape

down the shadows of a woodland path,

then summon my words and wait for the echo.

The space between