Towton Moor

Often on summer evenings I go for a stroll round a local field — at this time of year it sways like a sea with lush long grass. The field lies between the golf course and the cemetery.. I first visited the field shortly after moving up here from Yorkshire and it was to witness a re-enactment of the Battle of Dunbar by the Scottish Battlefields Trust. Oliver Cromwell, having beheaded the king, Charles I, and become ruler, marched north to consolidate his power in Scotland. He defeated the Scots at Dunbar in 1650 and advanced to Edinburgh.

We arrived — I went with my daughter and grandchildren — to find a row of tents, their occupants eagerly demonstrating a variety of antique crafts: wooden spoon making, herbal lotions and poultices, rush-mat weaving. Plump women in discoloured smocks sat over cauldrons of grim looking soup, their offspring running around dressed in sacks like peasant urchins. The men proudly, if somewhat comically, attired in their Roundhead or Cavalier apparel, clanked around with their flags and banners. And the odd anomalies: the 17th century pikeman leaning against a tree having a fag, the bonneted seamstress on her wooden stool thumbing her mobile phone. We moved on to the enactment itself to watch the opposing ‘armies’, pitifully undermanned, face each other across the field with a waving of flags and beating of drums, the shouts and commands blown away on the breeze. Then the battle, a brief melee of yells and grunts, fake blood and puny gunfire, and it was all over. Hesitant applause, then home again.

It is easy to mock the efforts of such worthy folk and their obsessive enthusiasms, but the intention is admirable. It’s a way of doing History, it’s an engaging afternoon out. Maybe they just like dressing up, who knows? The dissolving gunsmoke drifts away and with it my memories, back to my life in West Yorkshire.

*

Half an hour’s drive east from my home in Wakefield and I was at Towton Moor, the site of what is held to be the costliest and bloodiest battle fought on English soil. It occurred in 1461 and was the decisive battle in the Wars of the Roses, that wrangling for succession between the houses of York and Lancaster, the white rose and the red. Both lines issued from the offspring of Edward III. The sitting monarch was Henry VI, son of the victor of Agincourt, Henry V, and descended from John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. The Yorkist line, descended from Edward’s son, Edmund, felt they had a better claim to the throne. Their strongest candidate, Richard, Duke of York, had, however, been killed three months before at the Battle of Wakefield and his head, with that of his young son, Edmund, impaled on the battlements of Micklegate Bar in the city of York, ironically the Lancastrian stronghold. Richard’s eldest son, Edward, therefore took up the Yorkist leadership and in the south he was proclaimed king. He was a man on a mission, not only to cement his claim to the crown but to avenge the brutal fate of his father and young brother. This is what led to Towton.

The battle took place on March 29th, 1461. It was Palm Sunday — indeed in some old documents the battleground is referred to as ‘Palme Sonday Felde’. Every year, on that Sunday, an event is devised by the Towton Battlefield Society, with tours round the battlefield, complete with display boards, and other happenings remarkably like the ones at Dunbar.

I made it my custom, however, every March 29th, whether it was Palm Sunday or not, to go on my own walk round the whole area of the battlefield, about eight miles in all. If it happened to be a Sunday I could drop in on the event too.

My battlefield walk, marked in red

*

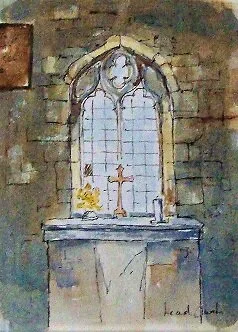

It is one such Sunday, a clear, bright March day. I park in a dusty lay-by next the the Crooked Billet pub at Lead (pronounced ‘led’) the site of a deserted medieval village. I cross a little bridge over Cock Beck, quietly rippling by….it will meander round the west side of the battlefield, then continue on its way to merge with the Wharfe at Tadcaster, five miles to the north. I wonder if rivers have memories. Through a gate, into a field of sheep. Standing in isolation in the middle of the field is a tiny church, St. Mary’s, Lead, on ground once owned by the de Lacys, an old Norman family. No longer used for worship, it is kept up by the Churches Conservation Trust.

St. Mary’s, Lead

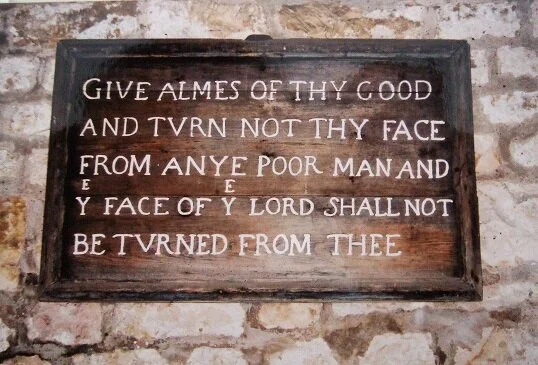

It flits through my mind that one warm summer’s evening I did a poetry reading here with a couple of fellow writers, followed by equally warm white wine. I open the heavy wooden door and sit inside for a while, reading the earnest exhortations painted on wooden plaques nailed to the wall.

*

March 29th, 1461. Palm Sunday, before dawn. The Yorkist commanders rouse themselves in the shelter of the chapel. The men, weary after a long march from the south and a strength-sapping encounter at Ferrybridge, emerge blinking from their blankets and bivouacs, grab a piece of bread and swig some ale. It is cold. A strong wind is blowing from the south and there are flakes of snow in the air. The mood is low…tired, anxious, and Norfolk’s contingent has not yet arrived. What will the day bring?

*

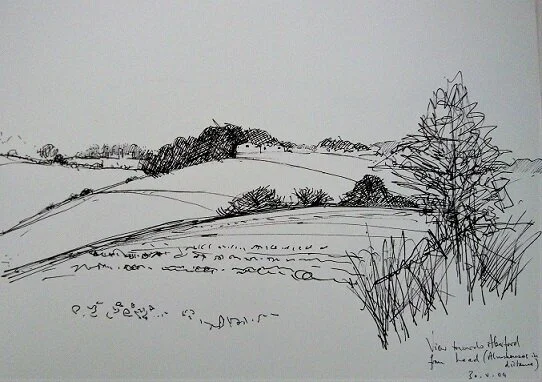

I leave the chapel and take the track through broad fields. Wide views: to the west, gentle farmland rolling away to Aberford and Leeds beyond; to the east, the plateau of the battlefield with its lonely, solitary tree in the distance.

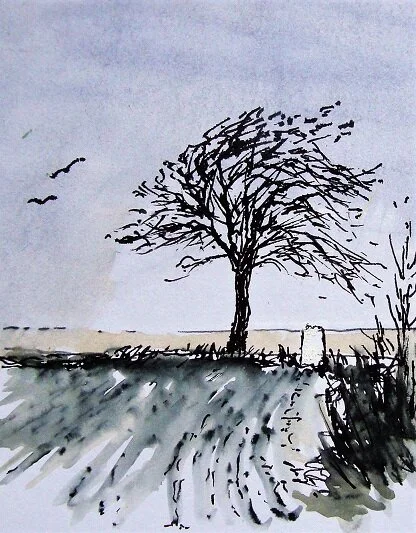

Looking west from Lead

A pheasant explodes from the hedge, its feathers the hue of heraldic stained glass. Soon I am on a farm track leading downhill to cross Cock Beck once again. I watch it disappear into the dark undergrowth to reappear and loop round Castle Hill Wood. The track passes by a farm where hens strut around the yard and the sound of hammering echoes from a barn.

Castle Hill Farm

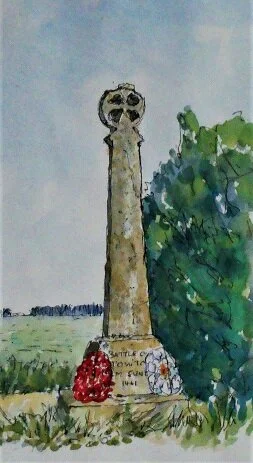

Soon I have to take to the road over the moor, but it is quiet enough, a B Road, my favourite kind of road. I walk along the roadside…..a tractor trundles by…..I imagine the sky ringing with the din of battle, and soon I arrive at a stone cross by the side of the road, the memorial to the Battle of Towton, 1461.

I am standing roughly at the centre of the battlefield, on a broad plateau, calm arable fields now, some with a slight green haze of new shoots. Behind me, the ground falls away to the valley where the Cock, now, perhaps, more of a river, flows north. Before me, on the horizon the only vertical is the solitary thorn tree. The sky is huge and darkening with storm clouds.

Towton Moor

*

Dawn has broken as the troops draw up in their battlelines. The men who camped in the fields at Lead have trudged up with the wind at their backs. It is snowing. The ranks spread far out across the scrubby plain….how many? Fifteen, twenty thousand? They know they are outnumbered by the Lancastrians drawing up to the north, facing them across a shallow dip in the land. The dryness in the throat, the churning in the stomach. Then, like relief, the command comes down the line to the longbowmen in the vanguard to let loose. The arrow shower, sped on by the wind, hurtles through the blown sleet and scythes through the Lancastrian ranks. The inevitable reply…but their arrows, blunted by the head wind, fall short. Now the Yorkists advance, collecting the enemy arrows and firing them back, many a Lancastrian soldier killed by his own arrows.

This is but the prelude. The volleys spent, the armies converge across the depression in the field, and throughout the day, hour after bleak hour, hand-to-hand fighting grinds on with lance, sword, mace, axe and the cracks of the handgun. The day swings this way and that, becomes a sluggish sea of blood and snow, the red against the white.

*

I continue my walk round the edge of the fields, the river running in the valley below. Soon I come across the first evidence of the day’s ‘event’. Up ahead, a man kitted out like a Yorkist archer, in claret tunic and tin helmet, accompanied by a youth bearing a standard, is describing the battle to a gaggle of visitors who struggle to catch his words and take snaps of the empty fields. The archer is one of the guides who set off at intervals from the event field to lead groups out and explain the action of that desperate day. I pass by in the opposite direction. Two crows with their slow black wingbeats head up the valley below me. Soon I arrive at a lane leading down to the river. This is the Old London Road. I take a short diversion and walk down the hill to find a neat little wooden footbridge crossing the stream. Somewhere down here is the place that came to be called the Bridge of Bodies.

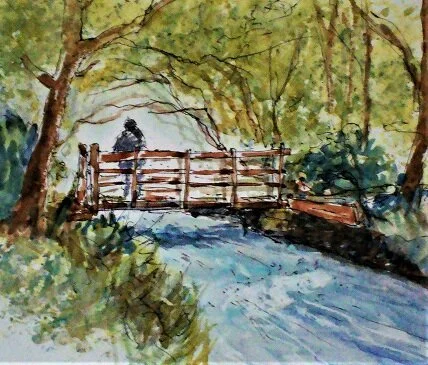

The footbridge over the River Cock

*

The bitter day wears on and the slaughter continues. The sky is dark with snow and mortality. A Lancastrian division has attempted an ambushing manoeuvre from the cover of Castle Hill Wood but it has not gone according to plan and their battle lines have been weakened. Yorkist spirits have also been lifted by the arrival late in the day of Norfolk and his reinforcements of five thousand men. Daylight is fading. There is no let up in the wind and sleet. Gradually, Edward’s forces push the Lancastrians back, wheeling them round so that their backs are to the steep slopes of the valley. There is no escape. In a blind, desperate fury of snowstorm and sheer, bloodied exhaustion, the soldiers slip and slide down the hill and a terrible carnage ensues. The place will be called Bloody Meadow. It becomes a rout, the Lancastrians fleeing for their lives, splashing through the red slush towards the river which is swollen with winter snow. They flounder and drown in the swirling waters. Their comrades trample over them using the piles of bodies as a bridge. Those who make it to the other side flee northwards towards York, hounded by the triumphant army of Edward IV. His rival, the pious Henry, has not ventured to the battlefield, deeming it more appropriate on Palm Sunday to spend the day in prayer. For days after, the River Cock and the Wharfe beyond run with blood.

*

I retrace my steps back up the hill and head towards the village of Towton where the event is taking place. Here is a scene much like the one I witness years later in Dunbar — the costumes, the tents, also falconry displays and archery contests. In a huge barn there are stalls selling history books, pamphlets, maps, memorabilia, and strange pies and tarts derived from medieval recipes. I am browsing rather aimlessly when I hear the rapping of a side-drum. At the close of the event a solemn procession with banners and drums winds its slow way up to a slight prominence where some local worthy recites a speech in memory of all those who perished on that dire day. The number of the dead is, understandably, disputed. Around thirty thousand would be a good guess. Huge grave pits have unearthed broken bones and smashed skulls testifying to the brutal violence of that day.

The crowd dissolves and the soldiers clink off to the pub but I have a few miles left to walk and will save my drink till later. I leave the Towton Battlefield Society’s event with its burger vans and balloons and return to the fields of my own imagination. I think of the victorious Edward advancing to York to find Henry and his wife, Margaret of Anjou, fled. He retrieved the heads of his father and brother from Micklegate Bar to bury them with the rest of their remains. Headless bodies, it was thought, forfeited the right to a decent resurrection.

Unfortunately, for the next couple of miles I have no recourse but to trek along the main road between Tadcaster and Castleford with only the litter cast onto the verge for company. It is not long, though, before I cross over and walk across a field lined with a queue of aged hawthorn bushes, bent like weary infantrymen. I step up my pace, for the clouds are gathering and there is rain in the air. At the end of the hedge I take a short detour up to the highest point of the plateau. Here stands a trig point and the solitary thorn tree. The myth tells that the Lancastrian nobleman, Lord Dacre, was slain here, shot with a crossbow by a boy perched in a tree of which this is supposed to be a descendent. I look out over the great space of what was the battlefield. There is the sound of distant traffic and the wind getting up. Metal detectorists still roam these fields, eager for remains. All I’ve ever found was a small Victorian medicine bottle, between the roots of this thorn tree as it happens. I took it home and washed it out…..it still stands on the top of my bookcase.

And so I leave the scene and head down through the misty draughts of rain to the village of Saxton, where, in the churchyard stands the grave of the said Lord Dacre, and where, more importantly, for me at least, I find the Greyhound Pub. Here I take temporary refuge and quaff the best pint of Sam Smith’s ale i have ever tasted, brewed just down the road in Tadcaster.

As I leave the pub to walk the last mile, I think about the madness of war. Shakespeare, in Henry VI Part 3, pictures the sad King Henry sitting under a tree lamenting the sad sight of a father realising he has killed his own son in the battle, followed by a youth similarly mourning the father he has just slain. The scene is fictitious, of course — we know that Henry wasn’t even at the battlefield, but the craziness has not diminished. Over twice the death toll of Towton was chalked up on the first day of the Somme. But there is a peculiar poignancy about civil war. And, despite the breathtaking advances mankind has made in science and technology, we are still fundamentally tribal, driven by divisions, if no longer of royal houses, of race, colour, religion and the attendant lust for power of our world leaders. The battleaxe, the lance and the crossbow have given way to the bomb, the bullet and the drone, but the mentality is the same.

I come down the short slope to the lay-by and sense, even after 550 years, a heaviness haunting these few square miles, like the dark raincloud I see sweeping up from the south. Perhaps I could squeeze in another pint at the Crooked Billet before I go home.

*

One summer’s day, after a trip to York, I was returning to Wakefield on the B Road over Towton Moor when I came to a tailback of traffic. Afterwards I wrote this poem.

Memorial

Driving across the plateau in high summer,

flanked by fields of wheat,

I pull in by a monument, a stump of pitted stone,

the details rubbed by time.

Here, centuries ago in other weather,

two armies hacked all numb day through sleet.

Unnumbered limbs soaked into the ground

till rivers choked and ran with gore.

I shiver when I see around the plinth

these fading wreaths of roses white and red.

In a mirage of afternoon heat

I drive away, glad to pick up speed,

my thoughts already turned to where I’m going,

till — oddly for this wide open road —

I see traffic backing up and slow to a halt.

Somewhere a siren sounds and lights flash.

I wind the window down. Soon engines cut,

releasing the landscape’s counterpoint.

A skylark’s liquid song ascends like souls.

Hammering from a barn echoes the clang

of desperate sword blades,

and through the corn a sound of troubled breathing.

Cars cough back to life and edge forward.

I take in the ripped verge, twisted steel,

smithereens of glass, and smell hot oil.

A policeman spreads sand.

Skulls can be split by a poleaxe

or crushed on a metalled road.

I know that when I drive this way again,

there’ll be roses wrapped in cellophane

tied to a roadside fence.