Another Day

In the corner of the car park at Cove, perched on the clifftop is a sculpture. A row of figures, women and children, coats blown by the wind, look out to sea, their faces full of anguish.

It is one of a number of sculptures made by Jill Watson commemorating the victims of a violent storm which raged off this stretch of coast on 14th October, 1881. Most of the 189 drowned were from Eyemouth, fifteen miles down the coast. Twenty-nine boats were lost, some wrecked on the rocky shore. The little village of Cove lost three of its four boats and half their crews, eleven out of twenty-one men. It is hard to imagine the tempestuous scene, looking out over the calm. grey sea today.

From the sculpture a steep path leads down the cliffside, then through a dark tunnel to the harbour — a couple of houses up against the cliff face, a boathouse, a sturdy breakwater and two old fishermen’s cottages, now just used to store equipment. Against the harbour wall of what was once a thriving herring port two small boats are moored. They still go out for crabs and lobsters.

Cove

*

Another day, an Autumn day. I leave the car park at Cove and turn inland, away from the sea and into the fields.

The mellowing leaves and feathery seeds of the willowherb, almost spent, line the path. Rosehips glow in the hedgerows….a reckless final flourish of growth before the cycle rewinds itself.

Rosehips

My back to the sea this time

I entered in Autumn the folded land

where the fields were freshly drafted

the birches slivers of silver

and the banked woods burned coppery.

But especially in this bell clear day

those rosehips

vermilion grenades hissing in the hedgerows.

Whatever swells in them wells as waves do.

What weight they bear I cannot tell

but they will brim and break

and I will hear the explosions in my sleep.

The field path comes out on a road and a side street leads up to the village square of Cockburnspath — a few rows of houses, a corner shop, a junior school and a church. A quiet place.

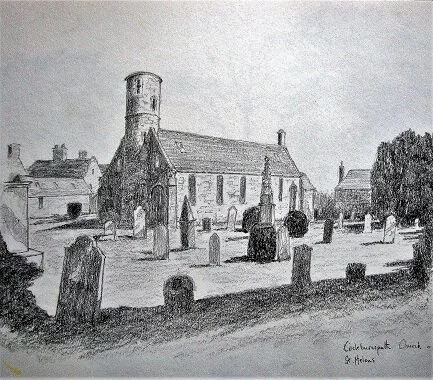

I wander into the churchyard of St. Helen’s, an early medieval building with a curious round tower at the west end. It is surrounded with a striking assortment of graves and memorials.

St. Helen’s, Cockburnspath

I like sitting in churchyards. I don’t mind the company of the dead. I imagine them lying there on their earthy beds. “You worry too much,” they say. “It won’t be long before you’re down here with us, and then you’ll wonder what all the fuss was about.” For living can be difficult, I think. I notice clumps of purple flowers growing out of the roof.

And then I am reminded that late in the 19th Century it was here in Cockburnspath that a group of artists gathered and painted in the surrounding fields. James Guthrie, George Henry, Edward Walton, Joseph Crawhill, among others, spent their summers here painting and living in a sort of Bohemian commune. They belonged to a group which came to be known as the Glasgow Boys. They rejected the polished finish and the often sentimental narrative of much Victorian art. They turned to J.M.Whistler for inspiration; he wanted to free art from literary and moralistic intent — ‘Art should be independent of all claptrap,’ he announced. They were also drawn to the earthy realism of the French artists, Jules Bastien-Lepage and Courbet.

Two paintings by Sir James Guthrie:

‘The Hind’s Daughter’ 1883

‘Schoolmates’ 1884-5

I sometimes wonder what the local ‘hinds’ (lowly farm labourers) thought of these moustachioed gents setting up their easels among the turnips and cabbage patches.

Artists at Cockburnspath

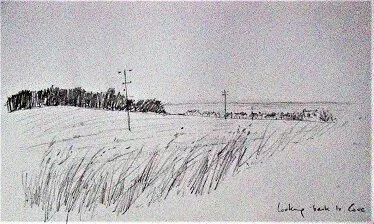

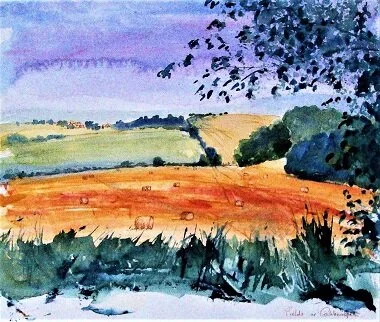

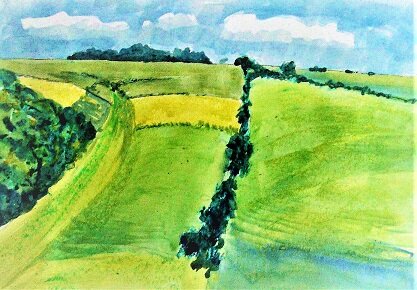

And so I leave the churchyard and take the lane out of the village, past the school and the shouts of children, and head for the open fields where the landscape spreads out around me and the sea glints in the distance.

Fields near Cockburnspath

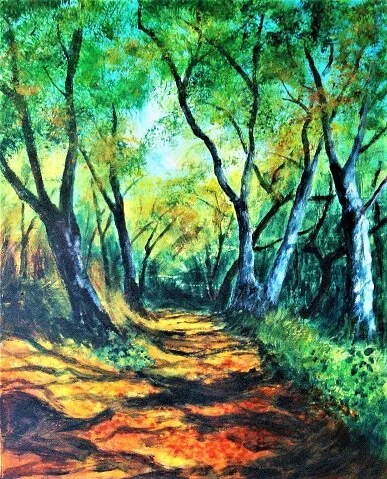

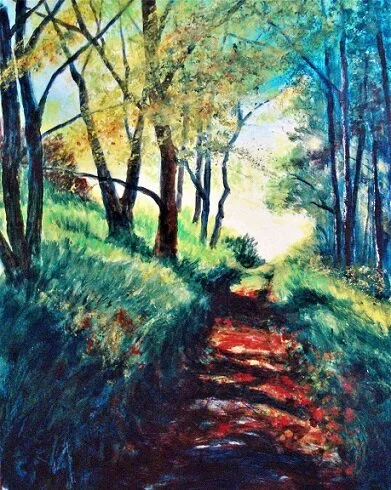

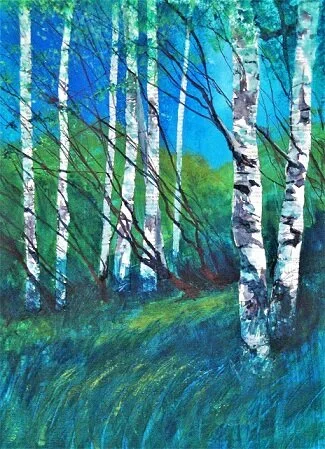

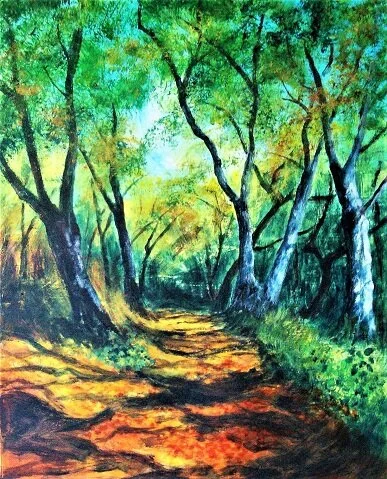

A line of trees on the far side of the field draws nearer and a gate opens into the woods above Dunglass Dean with its burn out of sight and earshot rippling along in the ravine below. The sunlight recedes and silver birches stand out from the shadowy woodland.

The Path above Dunglass Dean

Birches

The track drops down past a cottage with plants for sale (Put money in Tin) then joins what used to be the main road but which is now a quiet byway. It crosses Dunglass Bridge, an 18th Century structure which crosses Dunglass Burn. I peer over the parapet to the dizzying depths of the gorge below.

A short detour up a drive flanked by tall pines brings me to Dunglass Estate which once had a castle. It saw intense fighting during the conflicts with the English in the 1540’s, after which it was burnt down. This period of Anglo-Scots warfare is sometimes referred to as the ‘Rough Wooing’, one of its aims being to get Mary, Queen of Scots, to marry Henry VIII’s son, Edward, a failed attempt. Now, somewhat ironically, the estate specialises in up-market weddings.

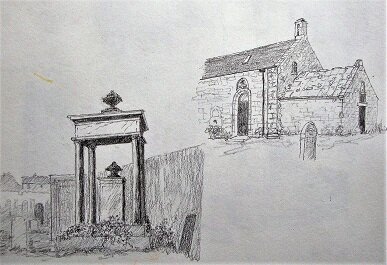

There still stand the remains of a 15th Century Collegiate Church, essentially a private church where a ‘college’ of priests were hired to pray for the souls of the landowner, at that time one Sir Alexander Home. Memorial plaques to him and his extended family still grace the interior of the ruins. The demise of the building came in the late 18th Century when it was sold off to a farmer who used it as a barn, smashing down the east wall to get his carts in. The place is now in the care of Historic Environment Scotland. It is a good place to sit among the masonry and open the coffee flask.

Dunglass Collegiate Church:

There are actually five bridges spanning the deep ravine of Dunglass Dean. From the road bridge already mentioned, I pass first under the railway bridge carrying the main Edinburgh - London line, dating from 1846, then the old A1 bridge (1922) which is now a bridge to nowhere, being bypassed by the modern A1 which runs alongside. The leaf strewn path along the top edge of the valley is golden with autumn leaves and the stream froths along far below, soon to flow through the rocks on the shore into the North Sea. The clatter and rumble of trains and traffic roars overhead, unseen.

Further Down the Path above Dunglass Dean

And then the last, and the oldest, bridge of all. It seems to have been constructed in the early 17th Century and some say it was used on a visit to Scotland in 1617 by James VI after his coronation as James I in England. It is just the width of a footpath and is shrouded in ivy and other vegetation. Now it marks the southernmost end of the John Muir Way before it becomes the Southern Upland Way which you can follow over the hills to Scotland’s west coast.

The Old Bridge

My path leads over the old bridge to the road back to Cove. The walk behind me is coloured by history and the windings of the imagination. Back in the car park I stand for a moment behind a sculpture: a row of figures looking out to sea. I follow their gaze. The waters are tranquil and the horizon is hazy. There is a hint of rain in the air.