Preludes and Fugues

The first thing I do when I go into my art room in the morning to do a bit of painting or drawing is to put some music on. It is almost always Bach, something from his keyboard music. There is a sense of calm control and at the same time an endless inventiveness that makes it good to work to. At the moment it is the Goldberg Variations. I sometimes look out of my window and see a reflection of the music in the rhythms of the sea:

Listening to the Goldbergs

the sea in my window

I catch the wide chord strummed

across the tide’s stave —

the tenor of the breaking surf

the ground bass of its deep swell.

I hear the undertow withdraw

with a percussive rumble and

its counterpoint the brittle riff

along the wave-crest.

And skimming above the blade-winged gulls

slicing the sky with their keening descant.

Bach wrote the piece for a Dresden nobleman, a chronic insomniac, whose protégé, a young harpsichordist, Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, would play it to him during his long hours of sleeplessness. Whether to help send him to sleep or simply to amuse him is not recorded. Nevertheless, it has become one of Bach’s best loved works. The piece consists of an opening aria, a tune of artless simplicity, followed by thirty variations, both technically brilliant and expressing an exhaustive range of moods and human feeling. When, an hour or so from the outset, the opening aria serenely returns, it is like coming home after a long and diverting ramble.

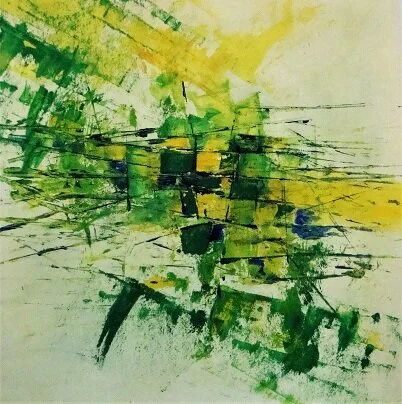

Tidal. An abstract in acrylic

Another Bach piece I often play is The Well-Tempered Clavier, otherwise known as the Forty-Eight, referring to the structure of the work. Bach takes the complete range of keys, both major and minor, and for each writes a prelude and an accompanying fugue. It begins in C major, therefore, and ends in B minor. He wrote it in 1722 and then, getting on for twenty years later, in around 1740, repeated the exercise, adding a Book II to the by now well and truly tempered clavier!

When I lived in Yorkshire some years ago, I attended an art class where each term we were given a subject to work on and produce some sort of end product. One such topic was ‘Diptych’, which we could interpret however we liked. In Art History ‘diptych’ commonly refers to a pair of related pictures, painted on wooden panels and hinged. This was to protect the painted surfaces but also for ease of carrying since they were often used as portable altarpieces. A well-known English example is the Wilton Diptych, which depicts Richard II, watched over by his guardian saints, being presented to the Virgin Mary and the infant Christ.

The Wilton Diptych, made c.1395

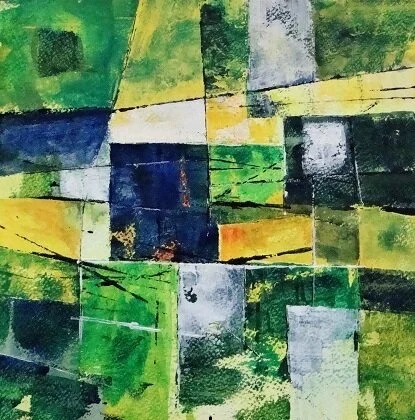

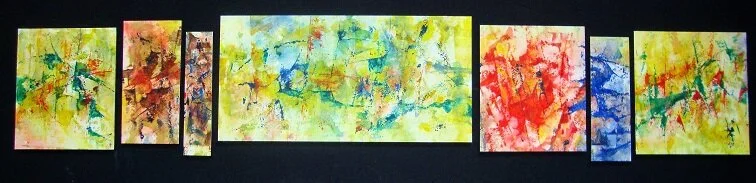

When faced with this topic I thought of Bach’s Forty-Eight, each prelude and fugue, related by key, being a sort of sound diptych. I set about doing some paintings in response to the music. It was an engrossing exercise. Did I ever really intend to do the lot, a pair of pictures for each of the twenty-four keys? Vain hope, but I did manage a fair few and I’ll scatter a few of them through this post. A project to be revisited, perhaps.

Prelude and Fugue in C sharp major

*

I discovered music in the cupboard under the stairs. You entered it by drawing back a heavy red velvet curtain. There in the dim light stood the gramophone, an imposing piece of furniture rather taller than my eight-year-old frame and wider. It looked like a sturdy aunt, with its shapely legs, its broad torso and the two knobbed doors of its ample bosom. These you opened to let the sound out. I had to stand on a stool to lift the lid and examine the inner workings. Inside the lid was a picture of a white dog listening to the horn of an antique gramophone.

I gazed in curious wonder at the turntable with its circle of green baize, the metallic pickup-arm and its round diaphragm nodding like a woodpecker, and the handle with a little wooden knob which you took from its clip and inserted in the hole in the side to wind the gramophone up. And most important of all, the little tin the size of a matchbox which contained the needles. There were two sorts: steel, for multiple use and a bright sound, and thorn, for a mellow tone and supposedly for just one playing. I found that you could prolong their life by revolving them in their holder or even sharpening them. All young boys carried penknives and my grandad showed me how to whet mine to a lethal blade with a carborundum stone.

Prelude and Fugue in B major

The lower part of the machine, the abdomen as it were, was a cupboard containing an assortment of black shellac 78rpm discs in paper sleeves. Some longer pieces came in handsome albums. It was a miscellaneous collection ranging from wartime songs and military marches to Hawaiian guitar music — In the Blue Hawaiian Twilight — and a dotty song called I wonder, I wonder how I look when I’m asleep…bom bom. And I was fascinated by a ten-inch record of someone playing a cello with birdsong in the background. I later learned that this was Beatrice Harrison in her back garden playing to the accompaniment of a nightingale. She also made the first recording of Elgar’s Cello Concerto in 1928 and was his preferred soloist.

There was also piano music — my grandfather on my father’s side had been a promising pianist so perhaps the records came down from him. Even at that age something stuck deep. Beethoven’s Moonlight Sonata, played by Benno Moiseivitsch, the last movement played at a headlong pace, no doubt to fit it on one side of a disc. And I was haunted by a little tune which it took me many years to locate. It was quintessential Schumann, the second of his Three Romances. It is marked ‘einfach’ , which means ‘simply’. I sat on the stool in that dark cupboard behind the red curtain, with the little white dog peering out above me, and listened to it over and over again.

Prelude and Fugue in G major

*

We moved to a new house and I started a new school, having miraculously passed the 11+. I came to possess my own radio, a grey, tinny device the size of a large loaf. I had to stick a wire in the back to get any sound at all and then walk round the room with it to get the best reception. I used to listen to the Top Twenty. At the time Lonnie Donegan was topping the charts with such songs as My Old Man’s a Dustman and Does Your Chewing Gum Lose its Flavour on the Bedpost Overnight…..

It was some years later, in moody adolescence, that the early spark kindled by Schumann’s Romance was rekindled. My father bought a radiogram, a fashionable item at the time, purchased as much for its looks as a piece of furniture as anything else. With it he brought us two 45rpm records, one of Shirley Bassey’s latest hits and Mendelssohn’s Hebrides Overture. I can’t remember what I thought of Shirley Bassey, but I was mightily stirred by the musical waters swirling round Fingal’s Cave.

Prelude and Fugue in E minor

I started to collect LPs, the pocket money I used to spend on Airfix aeroplane kits now saved up to buy records. Fortunately the major record companies issued modestly priced labels such as Decca’s Ace of Clubs — I started collecting Boult’s set of Vaughan Williams’ symphonies — and Pye’s Golden Guinea series — Elgar’s Second Symphony conducted by John Barbirolli. My first full price LP was bought with my earnings as a relief postman one Christmas when I was in the sixth form. It was the HMV recording of Berlioz’s Symphonie Fantastique, conducted by Sir Thomas Beecham with the French National Radio Orchestra. Apparently he wanted a French sound for a French work. I still treasure it, though now I have it transferred to CD.

Prelude and Fugue in D major

My awakening to the world of music beyond the popular classics came when I was bedridden with an attack of pleurisy, an inflammation of the lining of the lungs which makes for painful breathing. I was listening to my grey tin radio, the aerial hooked to my bedpost. It was tuned into what was then the Third Programme and I was half asleep when I became aware of a wonderful stream of music drifting over me and through me. What was this piercing poignancy, these tones shifting between cloud and sun, and this hauntingly different sound — just the interweaving of a few stringed instruments? It was Schubert’s String Quintet and it opened up for me a whole range of chamber and instrumental music I had been only dimly aware of. It is the music I listen to most often now. Strangely, it was Schumann, my first inspiration, who referred to Schubert’s ‘heavenly lengths’, and when you listen to the Quintet’s slow movement you can see why.

Prelude and Fugue in D minor

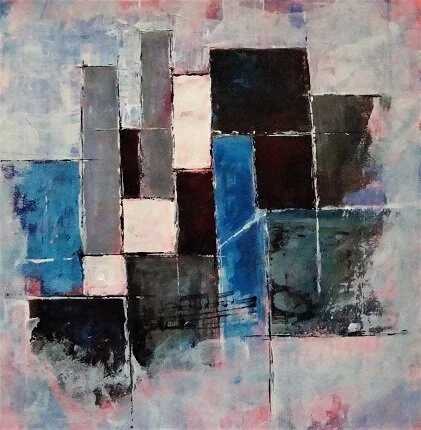

I came to the string quartets of Beethoven much later. Maybe I just had to wait for the right time. Now, I think they constitute the most extraordinary body of work. If I were stranded on a desert island I would be happy with these sixteen quartets and nothing else. And the last five or six are the most wondrous of all. My favourite is perhaps the one in C sharp minor, Op.131. It was written in 1826 just a year before his death, yet at a time when, even in his deafness, his head was swirling with musical ideas. It is in seven movements, two of them fleetingly brief, meant to be played without a break. He told his publishers that it was ‘cobbled together out of various things stolen from here and there’. It is quite a ride, from the grave beauty of the opening fugue to the stringent finale; it inspired a painting rather in the fashion of the Bach project. The grid of images represents the seven movements and their relative lengths.

Beethoven,s String Quartet No 14 in C sharp minor

Over time the LPs, with a brief supplement of cassette tapes, gave way to CDs. Fortunately, many fine historic performances were transferred to this format. I have read that it will not be long before CDs disappear and all music will go along the download route. Luckily, I have many shelfloads of CDs, quite enough to see me out. Music is transformative, like any art form, and can take you to other realms, strange new depths and undiscovered shores.

*

Once I used to go on the 110 bus every Wednesday to attend the lunchtime concerts at the Leeds College of Music. One day there was a concert given by a harpist, and I wrote a poem about it.

In from walls of stone

and rain edging to snow,

hugging our coats around us

we wind upwards

to find the globe of light

which is the recital room

where waits the harp,

that strung heart

ready to beat to adept fingers.

When she enters

her dress crackles like blue ice

then at her caress a music stirs:

plangent gusts of sound

gather and sweep,

astral arpeggios leap

from her fleeting hands,

glissandos of cirrus

dissolve in light

and as sleet streams

down the windows

we modulate to other skies

and break through different waters.

*

In these straitened times music is a constant companion, filling my home when I’m in and my head when I’m out, for my permitted daily walk. Which, as it happens, I am about to embark on, my round trip along the back roads and returning along the empty shoreline. When I get back I intend to make a pan of Scotch Broth, and while it is bubbling away go and do some drawing. I think the Goldberg Variations will still be in the CD player. I will press ‘play’ ,,,, again.