A State of Mind

What is it that makes some people especially, even intensely, responsive to nature? For some, like William Wordsworth, it is to be ‘much favoured’ in their birthplace. He spent most of his life among the fells and valleys of the Lake District.:

‘Fair seed-time had my soul, and I grew up

Fostered alike by beauty and by fear.’

The beauty we can understand, but the fear? He relates an incident. One winter’s night the young boy is up in the hills setting snares to catch woodcocks:

‘Scudding away from snare to snare, I plied

My anxious visitation; — moon and stars

Were shining o’er my head. I was alone,

And seemed to be a trouble to the peace

That dwelt among them.’

And then he steals a bird already caught in another’s trap, and feels the fear:

‘….and when the deed was done

I heard among the solitary hills

Low breathings coming after me, and sounds

Of undistinguishable motion, steps

Almost as silent as the turf they trod.’

Well, the lad was young, sensitive and impressionable. He felt guilty and it was dark. On another occasion, again at night, he takes a boat out onto the lake. He makes headway and delights in the sensation:

‘ ……..lustily

I dipped my oars into the silent lake,

And, as I rose upon the stroke, my boat

Went heaving through the water like a swan.’

But as he progresses further out, ‘a huge peak, black and huge,’ hitherto unseen, hove into view ‘as if with voluntary power instinct’ and seems to come after him. Chastened, he returns the boat and goes home ‘in grave and serious mood.’

‘ …for many days, my brain

Worked with a dim and undetermined sense

Of unknown modes of being….

…..huge and mighty forms, that do not live

Like living men (which) moved slowly through the mind

By day, and were a trouble to my dreams.’

So we have to see the fear as part of his ‘fostering’, beyond the sheer beauty of nature and a necessary ingredient of its awesomeness, which informed Wordsworth’s personality and creative powers.

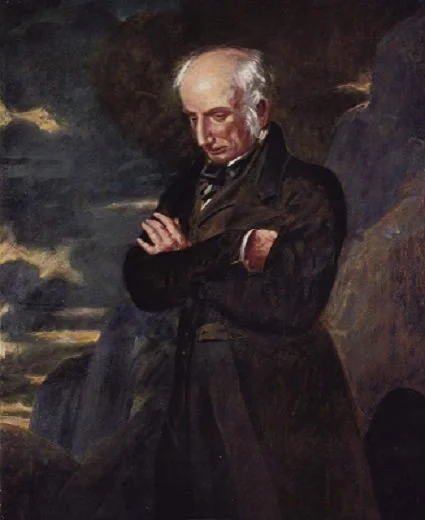

William Wordsworth (1770-1850)

*

For Gerard Manley Hopkins, nature in all its splendid intricacy was a manifestation of God, ‘The world is charged with the grandeur of God.’ And after a typically Romantic chastisement of leaden footed mankind for the ill effects of industry and urbanisation, he asserts

‘And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things.’

As with Wordsworth, there is something deeper in his response than sheer physical beauty, something ‘deep down’, a sort of force in the biological processes of Nature, an idea he suggests in ‘Spring’: ‘What is all this juice and all this joy?’ Whatever it is, Hopkins, a Jesuit priest, can trace it back to the Garden of Eden —

‘A strain of the earth’s sweet being in the beginning

In Eden garden.’

In perhaps his most ecstatic poem, ‘The Windhover’, the astonishing word-play in his picturing of the kestrel, the ‘dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon’, culminates in the breathtaking ‘stoop’ of the bird which action becomes a revelation of Christ, the poet’s ‘chevalier.’

‘Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!’

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-89)

*

Having neither the dramatic inspirations of Wordsworth’s childhood nor Hopkins’s supercharged religious fervour, I turn to Henry David Thoreau and his response to nature. He rephrases Hopkins’s ‘juice and joy’ thus, at the time he spent dwelling in a hut by Walden Pond in Massachusetts:

‘I enter a swamp as a sacred place — a ‘sancta sanctorum’ . There is the strength, the marrow of nature.’

Here is a recognition of the primal soup beloved of evolutionary biologists and ecologists which was and continues to be the laboratory from which all life emerges. And a recognition that we are part of it. ‘Man,’ says Thoreau, ‘is but a mass of thawing clay.’ So we humans and the natural world are involved in the same process in all its messy randomness. Describing the genetic, biological systems which produce the chaotic abundance and variety of life, the naturalist and writer, Richard Maybey, said, ‘A ceaseless, gratuitous, inventive bodging is what keeps the world going.’ That makes me feel at home.

Henry David Thoreau (1817-62)

*

Of course, these ideas, these pronouncements about nature and our attempts to understand our response to it, are but conceits. Wordsworth’s hills, Hopkins’s kestrel, Thoreau’s swamp are completely unaware of our intellectual or imaginative designs on them. Nature does not have a ‘meaning’. It just is. It is we humans who have an itch for meaning — meaning and meanings out of which we try to construct our lives, to attempt to explain the universe, to create pictures and poetry, which is the least we can do.

Salt Marsh

This lobe of the estuary

bay of silt scrawled

with pools and gullies

fills and empties like a lung

drowns twice a day when

the tide sidles in engulfs

then settles in a pane of sky…

and me standing on the edge

on spongy marsh-grass the tang

of wormwood and the curlew echoing,

I sense the mischief in it

watching the water wink as

it rises round my feet

and catches my reflection.

An insinuation….

nothing between us

the shifting surfaces our devious

windings furtive the way

we reshape ourselves

and indeed I would stay

with the salt marsh brimming

sucked into its secrets.

But wake to the peal of their wild cry….

that arrowhead of geese

clearing the air pressing north

*

Uprooted

This tangle of roots and felled branches

clutching at air, the pine knocked back,

gale rocked, just holding on…

…there’s something indecent about it,

the way the tide, surgical as a crow, stabs

and probes and prises, eviscerating the low cliff,

exposing its entrails, exhuming its bones.

Caught here, though the tide’s

now sulking in the shallows, out of reach,

I zip my coat up, tighten my bootlaces.

There are things I cannot keep at bay.

They gust in on the salt wind

pealing through the hollows.