Behind the Wheel

I took my driving test on what turned out to be cattle-market day in Aylesbury. I spent most of my allotted time marooned in a tide of bullocks. The examiner abandoned the emergency stop since it was impossible to build up enough speed to make the exercise worthwhile. Parking was out of the question too, every available place occupied by cattle-trucks and trailers. We did manage to escape the bovine melee eventually and I managed to contrive a hill start, although in truth Aylesbury is not particularly known for its hills. It was upon such evidence of my motoring skills that I was deemed worthy to receive a driving licence,

*

I have recently read a book called ‘Why We Drive’. Its author, Matthew Crawford, apart from lecturing in Cultural Studies at the University of Virginia, is a self-confessed car addict and also runs a motorcycle repair shop. Much of the book revels in the technical details of cars — the complexities of connecting rods and helical cut gears, for example — the salvaging of parts and the endless assembly and modification of engines. He belongs to a caste of what he calls ‘folk engineers’ who share their expertise, improvise, weld and reconstruct vehicles to their own specifications. When behind the wheel they are in direct touch with their own creations, every moving part of which they know intimately. The joy of driving becomes a personal expression of detailed knowledge, skill, awareness and control.

*

Shortly after I passed my driving test, I got a summer job in a local garage and car dealership. Soon I was moved from the petrol pumps to the showroom where one of my jobs was to fetch new cars from suppliers around the county. It was a high end dealership so I found myself driving Jaguars, Bentleys and Rovers back to the showroom, an intoxicating experience for an eighteen-year-old.

My first car was of a somewhat humbler variety. One of the garage hands knew an old lady who lived in a cottage up one of the numerous chalk valleys of the Chilterns. She had given up driving but still possessed a largely unused car in her shed. I gave her £24 and drove away in my own car, a black Austin 8 in fine condition.

An Austin 8

*

‘Why We Drive’ is, of course, not just about cars. Driving becomes a metaphor for skill, self-reliance, hands on control and managing risk, qualities the author sees as increasingly threatened by the ever proliferating self-programming of cars and the plethora of safety features, warning lights and digital technology, the ultimate end of which is the totally self-driving car. By taking so much out of our hands — literally — we become passive occupants of the vehicle, increasingly unable to make decisions or exercise real driving skills. This critique widens out to include the way the authorities — policy makers, planners, governments — try to control the way we live, particularly through the agency of big-tech. companies who have the means to analyse, monitor and infiltrate our lives through the influence of advertising, social media platforms and subliminal messaging, and so manipulate our responses, tell us what is fashionable, what we ought to like, ultimately to shape our identities. The thrust of Crawford’s argument is that the more we are catered for, the more our lives are directed to conform to certain acceptable norms, the less we can do, or think, for ourselves, the less we can function as autonomous individuals.

A Hillman Minx, a rather shabbier version of which I had as my second car

Matthew Crawford has a term for us as a species which I rather like — not homo sapiens but homo moto. From learning to walk to skateboarding, bicycling or driving cars, we are meant to move — it is part of our human wiring. We want to drive, not be driven, just as we need to find our own way through the complex traffic jams of life, not constantly be told what to do. We are in danger, he says, of becoming passengers in our own lives.

This creeping passivity does not go unrecognised though. Where I used to live, in an industrial town in West Yorkshire, the local library advertised ‘health walks’. These were not, as you might imagine, hearty hikes through the countryside but twenty minute plods round the pavements of the local estate. To add to the fun you would be guided by a ‘walk leader’. Grown adults were being taught how to walk. And a few years ago the National Trust published a pamphlet for children …and their parents, no doubt… telling them how to climb a tree, how to build a den, splash around in muddy puddles or roll down grassy slopes.

*

I enjoyed driving my Austin 8. It gave me a new kind of freedom. It allowed me. for example, to drive up to Lincolnshire to visit my grandma. The journey took most of the day and one such journey I remember was a dour, wet one with the wind and rain sweeping out of the east from the flat fens and levels. The Austin 8 was equipped with but a single windscreen-wiper; it was not considered necessary for the passenger to have one. On this particular day the wiper stuttered to a stop. Fortunately, the adjustment knob was positioned on the dashboard, so I was able to manipulate it manually. I completed my journey up the bleak roads northwards, one hand on the steering-wheel, the other resolutely working the windscreen-wiper.

It was a pity that I had to get rid of the Austin 8. I had to sell it to pay for the fine I incurred by reversing into a bread van. The collision, much to my embarrassment, sent trays of loaves shooting from its rear doors to bounce all over my car. I was charged with ‘reckless driving’. I calculate that, since that sad day, I have owned around twenty different cars. In the early days I could only afford ‘old bangers’ as they were called. Such cars wouldn’t be allowed anywhere near a road these days. Seat belts were still a few years’ distant and MOTs were just being rolled out. A starting-handle was often required to get the engine going. Yet we drove them around happily until they conked out and then we looked for another one. My brother-in-law had an old Peugeot and whilst he was driving it one day the engine dropped out, the mountings having completely rusted through. He simply left it on the roadside verge and walked away.

A Camping Trip to France in a Wolseley 1500

*

At one point in ‘Why We Drive’, Matthew Crawford questions the need for traffic lights. How often, he asks, do we find ourselves stopping at traffic lights when nothing is coming from any other direction? Red lights, he argues cause frustration, not to mention the pollution created by mass idling. And they actually cause more congestion when everybody sets off again at the same time. He recommends lights-free junctions where motorists are encouraged to exercise awareness, bonhommie and judgement when negotiating intersections. He cites Italy as an example, where, in Rome, what appears to be a chaotic free-for-all is ‘a spectacle of improvisation and flow that is beautifyl to behold as cars, buses, motorcycles and pedestrians weave among one another.’ Analysis of statistics about travel times, numbers of accidents and congestion indices shows that Rome is a safer place to drive than Washington DC with its infestation of speed cameras and red lights. Having commented on the development of Intersection Managers, automated traffic control systems using cameras, scanners, radar and photo-electric sensors., Crawford sums up his position thus:

‘Rules become more necessary as trust and solidarity decline in a society. And, reciprocally, the proliferation of rules, and the disposition of rule following that they encourage, further erode our readiness to extend to our fellow citizens a presumption of competence and good will. At the end of this trajectory, it becomes necessary to hand over our steering wheels to an Intersection Manager, who will solve our problems for us.’

Speed cameras are often vandalised. You see them burnt to a blobby, molten mass or daubed with black paint. They are, like traffic wardens, universally despised. It is not just that they are seen as devious, catching you out when you’re not looking or lurking round corners, but the strong suspicion that they are there not in the interests of road safety but to rake in the money for the local authorities. It is common to find them just before or just after dual carriageways, when you are quite reasonably and competently either getting up speed for the carriageway or gently reducing it afterwards. I have only just avoided losing my licence through speeding convictions, mostly for slightly exceeding the limit in 30mph zones, either at 5 o’clock in the morning when there is nothing else about or in unfamiliar Scottish towns frantically looking round for a road sign that made sense. Scottish authorities are particularly keen on speed cameras. As it happens, I have not incurred a speeding ticket for some time, since I have compiled a mental log of all local camera locations.

*

Yet another Wolseley and a somewhat younger me

Though light years away from the mechanical knowledge of Matthew Crawford, I somehow grew up knowing something about cars. I must have picked up a few things from that garage and also my father. It was a time when people just did more for themselves. My mother made and mended clothes; my father had a heavy iron last on which he reheeled our shoes. Car engines were more accessible, of course — it was an easy matter to adjust the points, put in new filters and replace spark plugs (or remove them and rub them down with emery paper and adjust the gap) Now many engine parts are shut up in sealed compartments and the running of the engine is controlled by a computerised engine management unit.

Moreover, cars needed more attention, especially the ‘old bangers’ I used to drive. When our twins came along and we had three children under the age of two, we bought a Morris Minor van to accommodate them. The side panels had been cut out and replaced by windows and a seat put in the back. I fixed a little car seat to the side wall for our daughter which left space on the seat for the boys. We wrapped them up securely and transported them in Co-op grocery boxes, side by side like little cribs. A regular occurrence with the van was the detachment of the exhaust pipe from the manifold, an event heralded by a sudden throaty roar from the engine compartment. Lengths of wire and liberal quantities of Gun Gum were required to fix it back again but the repair was ever but temporary. Failures at the other end of the exhaust system were remedied by silencer bandage and empty beer cans, of which I always had a plentiful supply. When on holiday once, the van suddenly lost its third gear — it just ceased to function. We soon developed the requisite skill to change seamlessly from 2nd and 4th gear without too much inconvenience.

My daughter Kate peering out of the window of the Morris Minor van

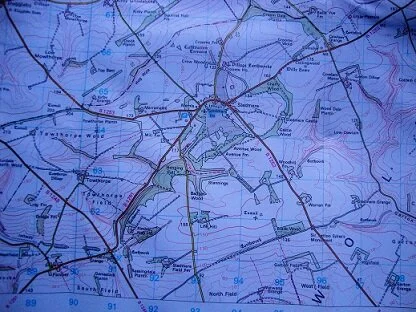

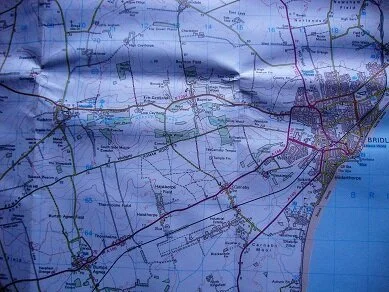

Part of the enjoyment of driving for me is, or was, route planning — getting out the road map, sometimes even the Ordnance Survey map, and plotting an interesting route, preferably using B Roads and minor byways. One of my favourite B Roads was the B1251/3 over the Yorkshire Wolds. We went that way on days out to Bridlington. Leaving the A Road at Fridaythorpe, the road rose up into the wide expanses of the Wolds, a well-surfaced and quiet road under huge skies. The joy of — to use a more antique term — motoring! I do not possess a SatNav, nor do I want one, and not because of the ludicrous mistakes they sometimes make, directing articulated juggernauts up rutted farm tracks, for example, but just because I prefer to find my own way.

The B Road across the Wolds…beyond Sledmere it is the B 1253

A car to which we were particularly attached was another Morris Minor, this time a convertible whose soft top folded down concertina-like to open us up to the elements. I bought it from a college friend of mine who had inherited a more modern car from some relative or other. When he was still the owner I was travelling home with him one Christmas from Yorkshire to Buckinghamshire where we both lived, as was Valerie, a large girl who occupied the back seat. Somewhere near Hemel Hempstead the ignition light came on. We were in light-headed mood and made up a little song, ‘Oh little red light, what do you portend? I fear we shall come to a horrible end..’ The end followed shortly afterwards when the engine died and we dribbled to a halt in a layby. It was, of course, the fan belt that had snapped. I had heard that in an emergency a nylon stocking served well as a replacement fan belt. So it was that Valerie gamely peeled off her hosiery, from which I fashioned a tight enough belt to see us safely home.

JFK

Another memorable occasion involving JFK, as we called the Morris (after its registration mark, not the American president who had been assassinated a few years earlier) was a wild open-topped drive through the snow one winter’s night. A group of us students had been singing folk-songs in a country pub called ‘The Cherry Tree’, perched up a steep hill a few miles out of Barnsley where we all lodged. We were in merry mood when we emerged from the pub having sung and drunk our fill to see that it had been snowing heavily meanwhile. If my accident with the Austin 8 could hardly count as reckless, our drive back to Barnsley that night would, I have to admit, qualify for the term. We piled into the little car and threw back the roof. Somehow I managed to slip and veer and slide down the hill through drifts of snow with all manner of chicanery, eventually arriving in the quiet streets of Barnsley, everyone singing drunkenly to the cold night sky.

The B 1253 continues over the Wolds

*

I’m not suggesting that such japes, along with transporting babies in cardboard boxes or operating windscreen wipers by hand, are anything but dubious activities. I’m just recognising that things were different then. Times have moved on and the roads have become mightily congested and potentially dangerous places and we need to build in as much safety as possible. Nor do I seriously suggest we should do away with traffic lights (not all of them, anyway), or doubt that it is a measure of progress that I don’t have to keep stopping to stick my exhaust pipe back on. But I have to admit that I can’t help warming to Matthew Crawford’s libertarian appeal to self-reliance, risk taking and freedom from excessive ‘safetyism’, traffic ‘calming’ and all the attendant surveillance to which we are currently subjected — the ‘steady erosion of contingency’ as he calls it. He himself admits, however, that to rail against what is assumed to be scientifically demonstrated as ‘advance’ is futile. Car manufacturers, in hock to the big tech. companies, have got it all sewn up. They control what counts as progress. Likewise, it is difficult to experience the joys of the open road in most contemporary settings. The thrill of driving can now be felt only on off-road tracks, at rallies or demolition derbies, or if you happen to be taking a trip across Siberia or the Australian outback.

The B 1253, with Bridlington in sight

One reservation I have about ‘Why We Drive’, energising and witty though it is, is this. The sort of people who might be able to accomplish the driving style the author commends — mechanically knowledgeable, skilfully adept at every aspect of the car’s handling, intensely aware of other road-users, finely attuned to the risks of the road — are strangely like…well, Matthew Crawford himself. And the vast majority of ordinary drivers just aren’t. Most people haven’t a clue what’s under the bonnet let alone how it makes the car go. Most people couldn’t change a wheel, though I believe that the majority of new cars do not have a spare wheel — the owner is provided with a puncture repair kit instead…good luck! And many people, to be truthful, are just bad drivers. I have sat cringing in the passenger seat as the driver shudders round a tight bend in top gear, or been required to get out and direct the driver into a perfectly normal parking bay.

However, ‘Why we Drive’ is a stimulating, inspiring and often funny book. His analysis of the march of digital technology and AI which promises progress, choice and opportunity while insidiously compromising our real freedom and personal identity is well worth taking seriously.

*

.

My last but one car, a Fiat Punto

When I got my present car, a Kia, second-hand needless to say — I have never had a new one — it was the first one I could lock with that little button on the key. I actually missed the act of inserting the key in the lock! You can draw your own conclusions about that, as you can when I admit a liking for manually changing gear in preference to an automatic gearbox, and a reliance on a map rather than a SatNav. The pleasures of being behind the wheel on the open road are harder to come by nowadays, but I shall continue to seek out the B Roads whenever I can.

A postscript.

A Vauxhall Cavalier

The biggest car I’ve ever had was a 1988 Vauxhall Cavalier, a dark green one. When my son, James, then about twelve, first saw it he called it a ‘beast’, It served us well. I attached a tow-bar and with our trailer we went off camping in the Summer holidays. It was a good car, a comfortable car but eventually, as was often the case then, it succumbed to rust. The rear shock-absorber mounting surrounds rotted away rendering the car unroadworthy.

I drove it to a local scrap-yard down by the River Calder at the end of a muddy track. The place was closed, the steel gates firmly padlocked. I left the car in the lane outside. A month or so later I had a holiday in sunny Corfu. On the way back, the flight path took us over Wakefield. I looked out of the window and saw, in a bend of the Calder, the scrap-yard, and there was my green Cavalier, just where I had left it, abandoned in the muddy lane. The scene soon passed from view as we flew on to a far from sunny Manchester.