The Mind's Traces

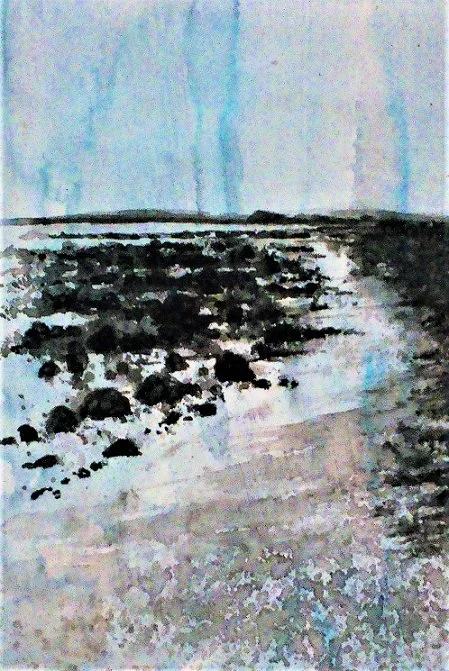

I am standing among the rocks on a shingly beach looking out to sea. The shore curves around me — to the left a low cliff topped by pine trees, to the right fading into the wide estuary. And, as ever, the waves coming in.

It is a complex experience. There is, for example, my knowledge. I know things about the rocks, what kind they are, how ancient they are. About the way the shore is eroding, the varieties of vegetation on the dunes…all things I know just from reading books. If I could be bothered I could know a lot more about wave mechanics and cloud formations. All thoroughly interesting, and second-hand.

But as I stand here I am not thinking about all this. I am experiencing, with a degree of pleasure, the sensation of being alone amid nature — the way my five senses are played upon, yes, but the response is also an emotional one. Call it contentment, excitement, even elation. This is a different kind of knowledge, intuitive rather than academic. Of course, why I experience it like this, in a way that I suspect is unique to me, is another question but it arises from aeons of genetic and socially conditioned algorithms which make me me. But it feels almost as though the natural environment and my person standing here are somehow connected, part of the same whole. An experience of Heraclitus’s ‘all is flux’?

*

Shoal of shingle

blade of banked sand

loose tongue salted

with thrift and wormwood

licking into the estuary

spreading

the sea’s gossip

the wind’s rumour.

Shifting spit

the tide’s afterthought

littered with driftwood

strewn with wrack.

Here

where I kick over

the mind’s traces

watch the past break

on the tolerant shore

dissolving absolving

*

Around two and a half millennia after sage Heraclitus, the French philosopher and Nobel Prize winner, Henri Bergson (1859-1941), proposed to counter the analytical, schematic explanation of knowledge by suggesting an inner, intuitive way of ‘knowing’ which is not tied to clock time but ebbs and flows like a tide in its own psychological time embedded in the eternal flux of evolution itself.

The movement of which he was part and which took hold in Northern Europe at the turn of the 19/20th century was called Vitalism. Like Heraclitus, Bergson thought ‘Nothing just is, everything is becoming.’ The force driving this process he termed the ‘elan vital’ , a sort of power, a vital impulse, which propels life onwards.

I’m not sure if I can grasp that particular dimension but Bergson’s ideas along with those of old Heraclitus appeal to my wayward way of thinking.

Henri Bergson (1859-1941)

*

The old Austin with threadbare tyres somehow made it up the muddy track to the top of the moor. My driver, a potter, had lived up here in her isolated cottage for decades. We slid to a halt, got out and tramped across the boggy ground to a scattering of gritstone boulders. She wanted to show me the cup-and-ring carvings on them.

Such carvings are widespread across Britain and the rest of Europe and date from the Bronze Age and the Late Neolithic. They consist typically of a small hollow surrounded by concentric rings; there is often a groove running from the centre to the outer edge…as you can just about see in the photograph. Yet their significance remains something of a mystery. Is it something to do with religion or astronomy perhaps? A territorial marker? Is it art?

We stood looking at them, discussing these things. I turned to my friend and asked, ‘What do you believe about them?’ She said, ‘I don’t believe in anything. I just have experiences.’

*

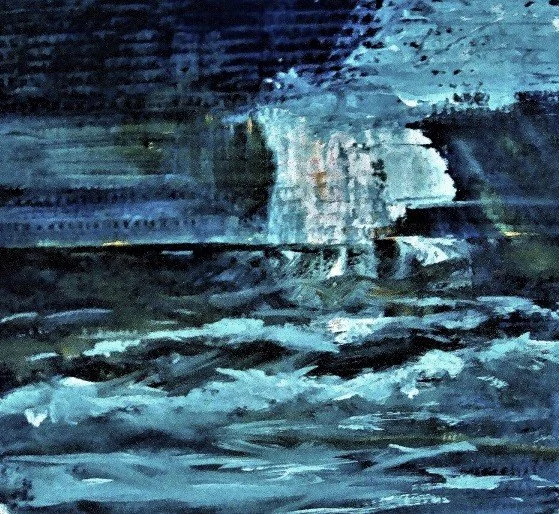

What I Saw

I took the path by the shore

where the bright wind played,

and this is what I saw:

a smooth and glistening rock

slumped in the shallows like a seal

a washed-up creel

I supposed was a giant lobster

an old mooring post

standing still as a heron

a shadow flitting up a pine trunk

I fancied was a squirrel

the hulk of an upturned boat

stranded like a whale

a fluttering brown leaf

I took to be a toad

a tree-trunk beached and bleached

gaping like a great white shark

a plastic bag in the sand

I mistook for a jellyfish.

I came to the edge of the sea

and peered into a rockpool.

I saw a face I thought was me.