Alma Mater

As I write this from my eyrie on the East Lothian coast, children south of the border are about to return to school after their enforced ‘lockdown’, but under conditions which many parents have greeted with incredulity and dismay. Children must sit the regulation two metres apart, ‘sanitise’ every time they touch something, undergo disinfection every time they sneeze or cough, queue at a distance for lunch or the loo, play in their individual demarcation zones and, if they have the misfortune to injure themselves, be comforted ‘at a distance’. Teachers are able, presumably, to access some kind of Hogwartian magic and cast a healing spell in their direction. Not surprisingly, many parents intend to keep their offspring at home rather than subject them to the tantalisation of seeing their friends again then forbidden to go anywhere near them.

I have been wondering how such a situation would have been handled in my schooldays. In some ways it might have been easier. At least we had the advantage of living in a pretty socially distanced society anyway. If my mum wanted to communicate with someone she had to physically go out and meet her. She couldn’t sit in the kitchen amusing herself with the breathless torrent of virtual companionship now available on the smartphone. When I wanted to see my friend, Fitz, I couldn’t sit in my bedroom swapping texts and selfies. I got on my bike and rode the three miles to his house.

One reason the un-lockdown proposals arouse such concern is that they are so at odds with current educational practice, where social interaction is key, the kids are all ‘guys’ who sit in groups, talk among themselves and roam freely around the classroom. When I went to school, even if we weren’t six feet apart we had to sit in individual wooden desks, complete with inkwell, arranged in rows pointing to the front. We never faced each other! Education consisted of a teacher standing at the front delivering information of some sort, then sitting down while we did exercises from a book. Apart from the odd surreptitious note passed beneath the desk, we did not communicate. We were not allowed to talk, let alone sneeze or cough. Admittedly, when the bell went for break, it was another matter. Having walked (DO NOT RUN!) down the corridor, in silence, we burst out into the playground yelling our heads off and threw ourselves into vigorous, often violent, games of tag or football. Even those less physically inclined would lurk in little groups in quiet corners. There was always the odd one who lurked alone. Some people are natural self isolators.

One of the ironies of today’s schooling is the taboo around touching, teacher on pupil, that is, though by some accounts it doesn’t apply the other way round. Despite the chummy sociability and meticulous pastoral care of the modern classroom, no touching is the rule. Even pulling apart two kids beating the hell out of each other can lead to a charge of assault. At least we could look forward to the odd clip round the ear.

*

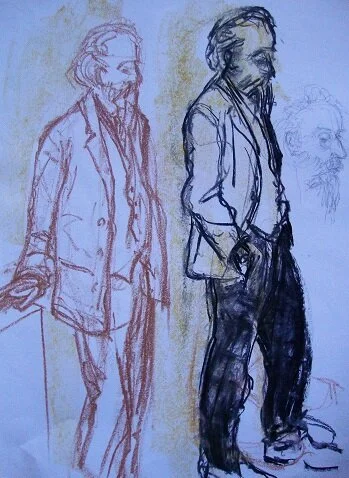

Through the mysterious time-shift of memory I summon up a handful of my old teachers, those who made an impression on me in one way or another. The illustrations are in no way intended to be their likenesses — how could they be? A few are from various life-classes I have attended. The others are sections of a large collage which I call ‘The Tenement of Ghosts’.

The Tenement of Ghosts

*

The last person I ever wanted to touch, or have touch me, was the woman it was my bad luck to have as my class teacher in the last year of junior school. Miss Nye came from New Zealand and had a voice like a dentist’s drill. She insisted on unwavering obedience at all times. If anyone aroused her displeasure, which was not infrequently, they had to go to the front and write their names on the blackboard. The list of wrongdoers then had to stay in at break and do extra sums. Sadly, the ear-curdling whine of ‘Name on the board, Lancaster!’ came all too often. I felt unjustly picked upon. of course, though I have to admit to once being discovered in the craft cupboard with my friend, Brian, attempting, in the absence of real cigarettes, to smoke lengths of cane normally reserved for basketwork.

At the end of the year when our class was set to move on to secondary school, Miss Nye left too. She was going back to New Zealand and we all had to learn a Maori earth-chant to sing to her on the last day. After the headmaster had delivered his fulsome farewell we sang our song. She stood there weeping into a little white handkerchief. I found this as hard to understand as the words of the Maori earth-chant. Perhaps they were tears of relief at not having to deal with the likes of me any more.

from ‘The Tenement of Ghosts’

*

I had passed the 11+, along with three of my best friends, to go to the Grammar School. The fourth, due to the iniquities of the system, was abandoned to the Secondary Modern the other side of town and our paths never crossed again.

We were confronted with an entirely new experience of school. An array of new separate subjects and, bewilderingly, different teachers for each. They wore black gowns and sat behind the Headmaster in Assembly like a row of roosting rooks. They were almost all men, though I do remember a Frau Gelblein who did her best to teach us German, and a young Maths teacher, Miss Webster, the only one we ever dared to play up. We once reduced her to tears when we set off stink bombs in her waste-paper basket.

A teacher who never wore a gown — I don’t recall ever seeing him in Assembly for that matter — was the Art teacher, Mr. Critchley. He spent most of his time in his art store which also served as his office, and he was an inveterate smoker, Players untipped. His lessons consisted of a minimum of instruction before he left us to it and retreated into his cupboard to light up. The first project he gave to new boys was to make a clay ashtray. Most found their way home to suitably impressed parents — you could always do with an extra ashtray in those days — while the less successful efforts ended up in a box in the tank cupboard.

I always liked art and was quite happy to be left to my own devices. Later, when, along with two others, I took Art for A-level, Mr. Critchley held little seminars in his smoky den, filling us in on Art History. I think he had difficulty in talking to little boys but he seemed at ease with us, encouraging us to pursue our own creative inclinations. He thought I should paint on a large scale and provided me with eight foot panels of hardboard to that end. The Art Room was at the top of a modern multi-storey classroom block. Leading off it was the tank cupboard which contained vast cisterns for the building’s water supply. More importantly, there was space round the edges for the three of us to hide ourselves away and work. I nailed my great stretches of hardboard to the wall and painted, using the economical medium of powder paint mixed with PVA glue. I was going through a quasi-religious phase at the time and painted a crucifixion scene with fiery torches in the background. I was very proud when it was hung up in the Assembly Hall for all to see.

Mr. Critchley rarely entered our domain but when he did what little he said was always pertinent .He never commented on the cigarette butts in the discarded clay ashtrays either.

Sketches in pastel and charcoal

*

My A-level English teacher was Mr. Trench. He had served in the war, apparently with some distinction, but had lost a limb in the process. He returned with the promise of medals and a tin leg. He was not a man to be trifled with. As soon as we heard him clanking down the corridor we rushed to our places and made sure we had our books open. Unlikely though it may seem, it was to this daunting character that I owe my love of literature. We did the Romantic poets. I suddenly found voices speaking to me in a language I understood. I was particularly excited by Wordsworth — we read the first two books of ‘The Prelude’ — an attachment that has lasted to this day. Perhaps Mr. Trench, through all the bloody horrors he had been through, yearned for the solace of nature.

from ‘The Tenement of Ghosts’

*

Mr. Barlow, the Woodwork master, was rumoured to be a vigorous preacher at some local nonconformist chapel. He conducted his lessons with religious zeal and had the odd habit of using the biblical ‘shew’ for the past tense of ‘show’. It was a word he repeated many times, as in, ‘Do as I SHEW you, boy.’ Our introduction to carpentry as first years was to make a small bedside bookshelf in order to practise mortice-and-tenon joints. When finished, he advised, the shelf should be able to contain a dictionary and a bible. The Christian virtue of succour for the afflicted did not come easily to him though. Once, when a shy and not particularly dextrous boy nearly sliced his thumb off with a chisel, Mr. Barlow called him an idiot and berated him for not holding the chisel as he had ‘shewn’ him, before packing him off to matron, a bloody trail in his wake.

from ‘The Tenement of Ghosts’

*

A faintly disturbing character was Mr. Clapper (‘Crapper’, of course, in our puerile argot) He taught Physics and had thin hair slicked back with brylcreem. He spoke with a nasal drone and had a disconcerting staccato sniff. When he had instructed us in the theory from his raised desk at the front and set us some practical task to do with springs and magnets, he would descend to our level and start creeping around behind us. We would hear his sniff approaching, then he bent over us to issue some admonishment or smidgeon of encouragement. He smelt of soap.

At hometime once, I was walking down the path past the staff car park when I noticed Mr. Clapper waving at me. He summoned me over and told me to go to Mr. Barlow and ask to borrow, please, two large screwdrivers. I went to the workshop where Mr. Barlow was tidying up. He selected the screwdrivers from his meticulously arranged rack and handed them to me, instructing me to hold them by the shaft. ‘You never know who will come running round the corner,’ he said mysteriously. ‘Now, run along and do as I shew you.’ As indeed I did, with the image of some unfortunate lad impaled on the end of a screwdriver flickering in my head. When I got to the car park, Mr. Clapper was standing by a pale green Hillman with its bonnet up. Inside was Frau Gelblein, yanking away at the starter button, to no avail. ‘You can stop that now, Frau Gelblein,’ droned Clapper. ‘Just leave the ignition on.’ I gave him the screwdrivers, handle first, of course. He took them, then he plunged them into the engine compartment and formed them into a cross. Sparks flew and the car spluttered into life, much to the surprised delight of Frau Gelblein.

When I recall this episode I always think of William Blake’s ‘The Ancient of Days’…

Mr. Clapper starting Frau Gelblein’s engine

When we were old enough to drink, my friend, Hogley, and I paid our one and only visit to the Railway Inn. We ordered our beer, then noticed at the far end of the bar in semi-gloom Mr. Clapper, sitting on a stool and staring glumly into a glass of Guiness. He appeared unaware of our presence and we wanted to keep it that way. We retreated to a far corner of the bar and tucked ourselves behind a wooden screen. We never went there again.

Much, much later, I wrote a poem about how odd and remote a teacher’s life can appear to one of his pupils.

Schoolmaster

Something gives him power.

His eye, perhaps, or sudden twitch,

the sweep of his gown, his clean heels.

Or could it be his voice,

unhuman, like a turned key,

admitting nothing?

And when he goes home,

does he squat behind the dark sofa,

screeching thinly?

Does he at midnight

shrivel and sleep in a glass jar?

I don’t know.

But when he bent over in carbolic closeness,

placed a lean tick on my page and made his noise,

doors swung open on endless corridors

and vacant wards.

from ‘The Tenement of Ghosts’

*

One schoolmaster whose character was less impenetrable than others was our History teacher. Fresh from university and scarcely older than we were, Mr. Tinker was a short man, like Napoleon, and to enhance his stature, instead of mounting a large horse, he conducted his lessons from the top of his desk. The normal mode of teaching then was for the master to sit behind his desk and dictate notes, as was the method of the dour Welshman who taught us European History. Mr. Tinker, who did British History, in our case the Tudors, was crazily inspirational. For him history was not about facts but interpretations. Dancing around on his desk he would hold up the respected textbook we had been set to read the week before. ‘Here we have Elton’s account,’ he said. Then, with a wicked leer, he cast it into the waste-paper bin. ‘Now, see what Silvester has to say,’ he went on, waving this latest text before us before drawing us into a fierce argument as to which view we took. This was a challenge, since normally we were not required to have a view. Mr. Tinker became very popular with his history set: he made us think, he was outrageously rude, not only to rival historians but to us as well — and, most pertinently, he introduced us to serious drinking.

Every Friday evening, Mr. Tinker invited us to meet him in the Old Town at six, in ‘The Eagle’. The Old Town was down in the valley below the New Town where the school was and where most of us lived. The main Oxford Road ran through it and was ideal for our purposes since it was lined with over a dozen pubs and old coaching inns. ‘The Eagle’ was merely the starting point for a steady progress up the High Street — ‘The George’, ‘The King’s Head’, ‘The Red Lion’, ‘The Hammer and Anvil’… Our animated historical debates continued until, as the evening wore on, the academic content began to lose its focus. Mr. Tinker would then entertain us with lewd banter which grew in obscenity the more inebriated he became. We always ended up in ‘The Black Bull’, a rough pub up a side street next to the cattle market. In the bar there was the novelty of a bowler hat nailed to one of the ceiling beams. Anyone tall enough to stand, feet flat on the floor, and fit his head into it was entitled to a free pint. Needless to say, it was well out of Mr. Tinker’s reach, but among our number was a quiet, thoughtful youth, Lilywhite. He was almost comically lanky and very tall. He earned his free pint whenever we went in, to the cheers of the gathered locals and the disgust of our history teacher.

There followed the weekly ritual of getting Mr. Tinker, by now scarcely able to stand, back up the hill. The New Town was the location, not only of the school but also of the station, the last outpost of the Metropolitan Line. Mr. Tinker lived in Harrow. We pushed, pulled and half carried him up the road and dragged him onto the platform where the train stood, as if waiting. We wished him goodnight and shoved him on as the doors were closing. It was said that he frequently failed to get off at Harrow and had to spend the night at Baker Street.

Mmmm…..

*

The final word must be left for the Headmaster, Mr. Savage. He was a tall man with a hooked nose and piercing eyes. When he swept onto the stage for morning assembly, his gown flying behind him, he resembled a large crow on the lookout for carrion. Apart from these daily appearances he was rarely seen, the fear he inspired only intensified by his remoteness. Assemblies seldom ended without some hapless victim being summoned to ‘meet’ him in his office. It was from him, when I was in the second year, that I received my only caning. The occasion was not, however, down to any particular wrongdoing on my part. It just happened to be the day he caned the whole school.

After the routine announcements at the end of assembly, instead of striding out he remained where he was and fixed us all with his piercing eyes. A grave misdemeanour had come to his attention, he announced. A school cleaner had reported a sighting of obscene graffiti in the toilets. It would be better for all, he said, if whoever was responsible would stand up there and then. No one did. Then he intoned, ‘You all know the words I mean’. And he began to recite them, slowly, icily, pausing between each one for maximum effect. ‘P-ss… Sh-t… B-lls…’

The staff ranged behind him shifted uneasily, twitching their gowns. But Mr. Savage hadn’t finished. He went on…. ‘W-nker….F-ck ...C-nt…’ I sensed some of the older boys behind desperately trying to stifle their mirth, but we younger ones sat aghast at this torrent of profanity. Some of us had only a shaky knowledge of the vocabulary anyway but to hear it from the lips of the Headmaster was shocking in the extreme. He concluded by giving us till break for someone to own up, otherwise he would punish the lot of us.

And so it was that after break the whole school was sent, class by class, to line up outside Mr. Savage’s office. The secretary told us to stand in alphabetical order. The Headmaster’s looming form then appeared in the doorway, brandishing his long, whippy cane. We filed past, both hands held out, and he delivered a stinging blow on each. I was somewhere in the middle of the line so I had time to get only moderately terrified. But I did feel sorry for my friend, one of Polish parentage, Zemkinski.

Portrait

*

For all their peculiarities, which naturally seem stranger in distant retrospect, these teachers managed to impart some sort of education to our emerging personalities and for that I am grateful. Mr. Tinker wouldn’t last five minutes in any kind of school today, but I still read history books with something of the critical eye that he encouraged. I still appreciate a good pint of bitter too. I’m not sure how much eccentricity is allowed in schools these days. Not much, I suspect, and even less in the sanitised post-lockdown future that the current cohorts of pupils will have to conform to. I wish them all the resilience, adaptability, and patience they will need, with a bit of good humour thrown in.

*

Note. The names of the teachers mentioned above are, of course, fictionalised. Some of them, Mr. Tinker for example, might not yet be dead! I should think Miss Nye has passed on — though it is not beyond imagining that she is now the oldest woman in New Zealand.