Churches

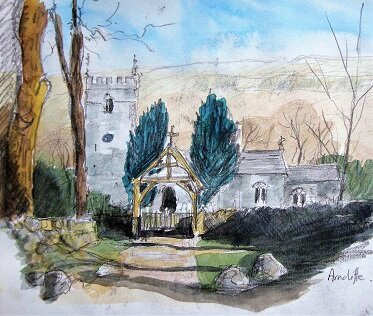

An hour’s drive would extract me from the city of Wakefield, manoeuvre me through the congestion of Leeds, release me onto the open roads past Otley and Ilkley and deliver me into the open arms of the Yorkshire Dales, Wharfedale the most accessible one. I would set off walking from Barden Bridge, or Grassington, Kettlewell or Buckden and spend the day up in the limestone hills. One of my favourite excursions was to branch off into Littondale, park at Arncliffe, climb up and over Old Cote Moor to Kettlewell, then back through Hawkswick and along the banks of the little River Skirfare to Arncliffe. But before I went home I always spent some time at the church, St. Oswald.s, wandering around the churchyard, popping inside if it happened to be open to look around, do a few sketches or just sit for a while.

St. Oswald’s, Arncliffe, with Old Cote Moor beyond

Charles Kingsley stayed with friends here once; walking by the river inspired him to write ‘The Water Babies’.

I am not a churchgoer, not in the Sunday sense, but I like churches. And in every village or hamlet, even if not much else, there is a church of some sort. Churches belong to our landscape and are an indelible part of our history and culture. Even Henry VIII’s attempts to delete them did not entirely succeed for the very ruins he left behind have become iconic tourist attractions. In Yorkshire there are some famous ones — Bolton Abbey, Fountains, Rievaulx and, further south towards Rotherham, Roche Abbey. Here are some pictures I have done over the years: Fountains, Rievaulx, Roche Abbey…..

*

The first church I can remember was a small pinkwashed building perched on a chalky ridge of the Chilterns where I was taken to be baptised. I must have been five or six at the time. My parents had shown no interest in baptising me before but at the arrival of my youngest sister it was deemed the proper thing that we should all be done at once. This was mainly at the prompting of the lady of the Big House where my father worked on the farm. She acted as godparent and brought her own children along too, one of whom was William, my best friend. When my turn came and I was standing at the font with the vicar intoning something and sloshing water over my head, my eye was caught by William, who chose that moment to pull a preposterously grotesque face. I burst into a fit of uncontrollable giggling and thus it was that my relations with the Almighty got off to a disappointingly unpromising start.

Afterwards, nevertheless, I spent a happy boyhood mercifully free of religion. My mother, much later, told me that she had lost her faith in the war, as did many others. As far as I recall, my father never expressed any interest in religion, though biblically inspired oaths frequently passed his lips.

Later, after I had moved north, I transposed my boyish innocence about anything religious into a poem. I had an allotment at the time and there was a church nearby with a large tree overhanging the east end.

Out on a Limb

There’s a black church and acres of gravestones.

Then a giant chestnut-tree with branches that swing down

and scrape the stained glass.

It’s all sound and then quiet —

the organ hoot, the hymns beyond,

then only leaves again and cool.

Sometimes an Amen moaning like a gust of wind.

But I can’t see through the dark glass.

They are old women in long coats.

I think they kneel on a stone floor whispering clouds of breath.

Their men are dead or in the allotments.

I go there sometimes, down by the canal.

Sheds and tin sheets and netting,

the ground steaming under a round sun.

Their gentle strange fingers

tying the fruits up and rubbing tobacco.

Earth boots and the spades shaking the soil.

An old man has a hut full of white doves.

He put one on my fist.

Suddenly the organ blurts when the big door sways open.

The priest’s there, white under the branches,

his wisp hair blowing.

Then they come out, the women, their funny smiles.

They shake his hand and take a leaflet.

Their sticks tap down the path below me.

I watch it all. I like it up here,

out on a limb,

the boy in the tree..

The tree in question has since been felled, a danger to the fabric of the church.

*

I became interested in churches when I studied architecture as part of A level Art. Our teacher, Mr. Critchley (you might have read about him in an earlier blog, Alma Mater), took us around the county to examine important examples. I recall a visit to Wing in north Buckinghamshire to look at the Anglo Saxon stonework in the church there.

Wing Church..Anglo Saxon arches above a much later window.

This coincided with a developing enthusiasm for history and archaeology, my hikes and bike rides in those days leading me not only to churches but to hill forts, castle ruins and old boundary ditches, anything, in fact, to remove me as far as possible from the modern world.

*

Another reason I like churches is that they are great to draw, and not only for the peculiarities of their architecture but for the settings they stand in. When I lived and worked in Yorkshire I was keen on running and one of the races I entered took to the roads and tracks of the wide, rolling landscape of the Yorkshire Wolds. About half way round we passed through the little village of Weaverthorpe on the edge of which was a church flanked by tall trees. After the race I drove back that way to stop and have a look. I entered through a lychgate. The narrow tower was very early with Saxon windows, and the building stood in what was effectively a flower meadow. I felt a strong sense of what can only be described as the spirit of the place.

St.. Andrews, Weaverthorpe

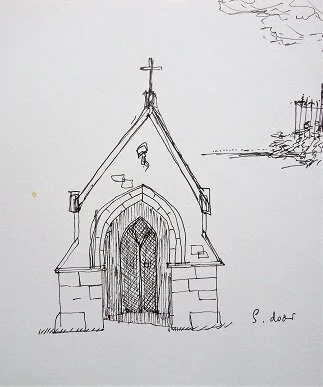

Sometimes I drove out into the flat landscape to the east of Wakefield in search of churches to draw. One day I found one — not far from the site of the Battle of Towton — in the small village of Ryther, on the banks of the River Wharfe just before its confluence with the Ouse at Cawood. I spent the morning engrossed in the details of the building and sitting in the peaceful churchyard drawing. Here are a few sketches:

All Saints, Ryther

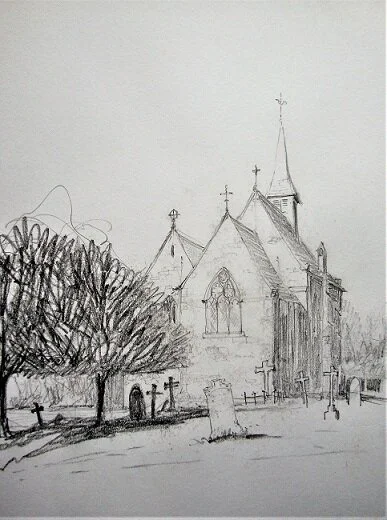

And further south in the Pennines I used to take a lengthy ramble over the open moors and along the wooded valleys around Bradfield. Half way round I’d stop at the Plough in Low Bradfield for a much needed pint. Somewhat cruelly the next section of the walk was a severely steep climb up to High Bradfield. Near the top of the hill — where, incidentally, there were the ramparts of an old motte-and-bailey castle hidden amongst the trees — was a church, its tower striking up perpendicularly from the steep slope. I never went inside St. Nicholas’s but I always stopped there to take in the view and get my breath back.

St. Nicholas’s, High Bradfield

*

Somehow conjoined to my historical and architectural interests was a peculiarly adolescent phase which I look back on with amused embarrassment. It would be wrong to call it religious since it had nothing to do with God and certainly did not prompt me to start attending church. It was more a romantic fantasy, an escape into a kind of sham mysticism in which I perceived myself as a type of visionary hermit. I suppose it embodied a yearning of sorts, a reaching out for a depth of meaning or emotional connection I hadn’t got. And which, had I had the gift of foresight, I knew I would never get. I smile wryly when I see still on my shelves those dusty old black Penguin Classics I bought in the ‘60’s. Richard Rolle, ‘The Fire of Love’ — it was an odd coincidence, when I moved to Yorkshire, to discover that the 14th Century mystic was known as ‘the hermit of Hampole’, a little village I passed through each time I made for the A1. And Lady Julian of Norwich, her ‘Revelations of Divine Love’. She was an anchorite, another solitary, and became very ill, close to death. She then experienced a series of what she called ‘showings’, holy visions, following which she made a full recovery. Her most famous words are these: ‘All shall be well and all shall be well. All manner of thing shall be well….’ And I must admit that, even without the holy glow in which she affirmed these words, I find a consolation in them. They just manage to leap over the constraints and worries of everyday life to some place where…..where ‘all shall be well.’ When I read these books as a teenager I had very little idea of what they were really about, but it pleased me at the time. That phase was, thankfully, short-lived.

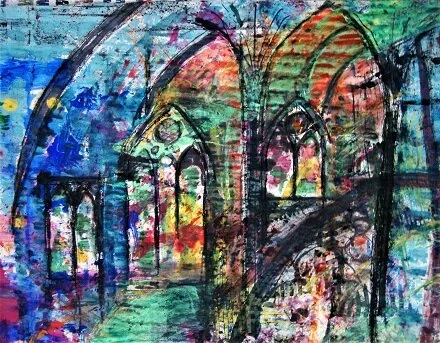

Gothic

*

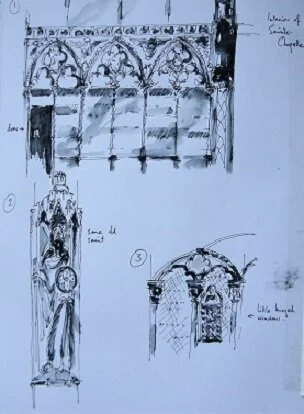

Yet churches have somehow within their fabric a power to move and inspire. We are drawn to them as by a forcefield somewhere deep in the communal psyche, somewhere that sups from a cauldron of primitive fear and superstition and need. When I retired from full-time teaching I spent one of the best years of my life doing a Diploma in Art and Design at Wakefield College. Apart from the lovely Dilys, I was the only mature student — all the others were young 18 or 19 year-olds hoping to go on to University or Art College. I found it completely energising to spend a year in their company, so full of life and fresh ideas were they. Part of the course involved a winter visit to Paris, where we explored art galleries, museums, the catacombs and much else as well as enjoying the excellent bars and restaurants of the district. I remember sitting with Dilys at a pavement cafe while sparrows ate cake-crumbs from my hand. We also had to collect material for a project to be completed back in Wakefield. I based mine on Notre Dame Cathedral. On the last day of our visit I remember sitting down inside, letting the crowds of visitors drift by….’Dilys has gone her own way,’ I noted in my diary. ‘Here is that characteristic hush, the loud, echoing hush, nevertheless, of a busy cathedral…..the piped plainchant, the lavish crib, still up in February, complete with water feature….the solitary woman waiting by the confessional..’ And of course I drew the place, along with other stunning ecclesiastical edifices. I found the technique of drawing with a fountain pen then tinting it with clean water very handy.

Sacre Coeur and, below, Sainte-Chapelle

Notre Dame

Our project bore the title Paris in the Park since we had to exhibit our creations outside the college building in Wakefield’s Thornes Park. I made a fragmented, multi-faceted image of Notre Dame from strips of wood painted like stained-glass and set with mirrors and strange faces. The piece was then strung up in a tree with fishing-line. Under a pile of leaves at the foot of the tree I concealed a CD player playing the music of Perotin, who composed for Notre Dame in the early 13th century.

*

I cannot deny the resonances which echo in the atmosphere of churches, but in truth I have never managed to believe in God, and not for want of trying. I did go to church for a time. I think I gave it a good shot. I even got confirmed and at some point found myself giving sermons at a sister church on the nearby council estate. I made good friends and we had happy times going on holidays with other families. We went to France once and stayed in a windmill and swam in a lake at night.

But somehow it couldn’t last. Whilst on a church holiday at a Christian Centre in Cornwall, I went for a run one morning along the narrow lane and down the steep cliff path to the shore. It was a fantastic day…blue sky, the surf rolling in and over the yellow beach….. the sort of day that would for many people confirm their belief in a wonderful creator God. And indeed it was wonderful and the scene moved me with its sheer beauty, almost to tears. But all the time I was thinking, ‘What has God got to do with it?’ This was the workings of evolution, astonishing, phenomenal, beautiful in its own right without recourse to any supernatural agency. And what’s more, I thought, I, with all my elation, all those buzzing neural networks clicking away in my brain, I am part of it. My experience on the beach that day was a road to Damascus in reverse.

So I left the church. I have no grudge to bear and feel no ill will for those who have religious faith. I know so many who are fine, genuinely good, sincere people. For me, though, I just didn’t get it and still don’t. God remains for me a three letter word with a big hole in the middle.

The Cherry Tree

I look out of my window

where the cherry tree’s thick pink swirl of blossom

sweeps like a magician’s cape

in the mad wind.

I sit here thinking what it means

to enter the kingdom.

My mind wants scaffolding,

firm ladders and planks to stand reasons on,

to balance arguments and weigh truths.

Then I wonder what it would be like

to be whisked out of this window,

to cling to the branches of the cherry tree

in all this wind, drenched by pink blossom,

praying that the boughs would hold,

trusting that the roots ran deep.

*

One of the oddest churches I have visited is St. Enedoc’s on the Camel estuary in Cornwall. We had a family gathering in Padstow and crossed to the other side on the ferry. The church squats in a hollow of the sand dunes in which once it was completely buried save for a hole in the roof through which the vicar gained access. Now it is unearthed and on that day was delightfully decked in wild flowers. I did find it strangely symbolic, though, the church shipwrecked in the shifting sand. I was interested to find the gravestone of John Betjeman in the churchyard. He was buried here in 1984.

St. Enedoc’s

John Betjeman’s grave

Certain churches in the Lake District stand like landmarks in my memory. I once spent a solitary weekend camping in the pleasant but relatively undramatic country between Lake Windermere and Kendal. It was near the little village of Underbarrow which had a good pub where I drank and a fine church where I painted.

All Saints, Underbarrow

I have sat in Rothay Park under the spire of St. Mary’s in Ambleside while the children ran around and played football. I noticed the workmen faithfully repairing the fabric of the structure while birdsong issued from the surrounding vegetation.

St. Mary’s, Ambleside

scaffolding and ladders

stacks of slate

buckets and trowels

ready for the mortar

and the jostling dead

blooming

lively with daffodils

while from the dark heart

of the holly tree

a blackbird opens his throat

and gives it all he’s got

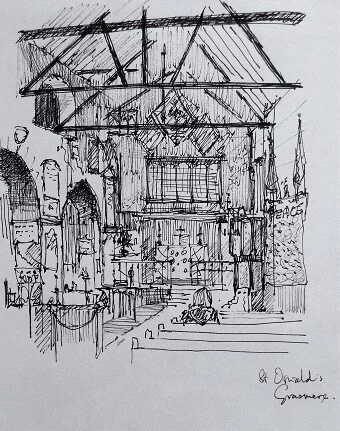

In nearby Grasmere I have often slipped into St. Oswald’s Church, having bought my gingerbread and lingered by Wordsworth’s gravestone, and simply sat there. At least if you are sitting alone in a church nobody asks you to move on.

Inside Grasmere Church

*

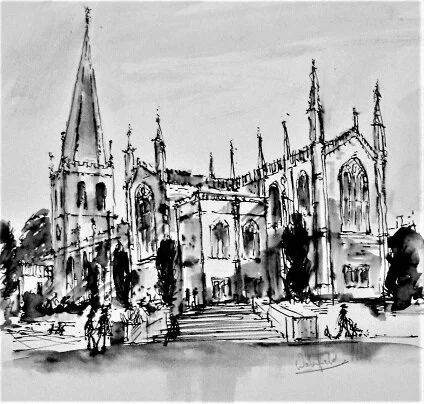

When I visit my son, Andrew, in Wakefield, I usually have an hour or so to wait before he gets home from work, so I have a pint of Tetley’s in the Black Rock then go and sit in the cathedral next door. .As I find a chair in a quiet corner — yes, they have chairs now….the pews were removed (to a huge outcry, needless to say) as part of the modernisation programme and sold off to congregants ‘randy for antique’ in Philip Larkin’s words, presumably to reappear as garden seats or lovingly polished in their living rooms. As I find a chair in a quiet corner, I wonder if I should feel guilty, given my lack of faith, to be feeling a sense of peace and tranquillity in the lofty silence of the place. Am I somehow freeloading on the centuries of devotion and prayer which have soaked into these walls? I don’t know, but, again to paraphrase Larkin in his great poem, ‘Church Going’, it pleases me to sit in silence here, wondering perhaps what will happen ‘when churches fall completely out of use’. I stare uncomprehendingly at the crucifixion pinned to the rood screen — I have no clue what it means — and consider how this beautiful church and the religion it stands for has witnessed, and often condoned, the most inhuman of cruelties — inflaming religious wars, burning ‘heretics’, drowning ‘witches’, abusing children, sitting on lavish assets of wealth and property. I wonder why I turn off my radio at thirteen minutes to eight in the morning when the pious platitudes of ‘Thought for the Day’ come on.

I don’t know the answers to these conundrums, but as I sit here in this remarkable edifice, its empty spaces airy as an aircraft hangar, I am thankful for somewhere quiet, dry and free, where I can shelter from the rain and draw a few pictures.

Wakefield Cathedral