Doon Hill

Doon Hill is within easy walking distance. It sits unassumingly just beyond the main travel arteries connecting Scotland to the South. At a mere 600’ it can hardly be said to ‘loom’, yet its prominence as an outlying spur of the Lammermuirs has lent it a historically strategic importance. As I make my way in its direction I pass the cemetery and I’m reminded that I am treading on ground once bloodied by soldiers fighting for control of this lowland gateway between Scotland and England. And there are further reminders of man’s fleeting mortality ahead, on the hill itself. But I have to get there first.

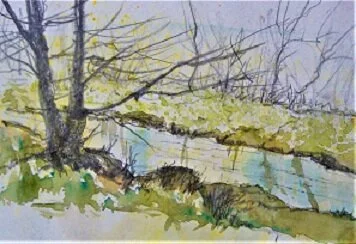

Brox Burn

I turn off the road and follow a track to a small settlement of cottages. I am accompanied by the Brox Burn rippling along in the spring sunshine. I follow it beyond the houses until it disappears underground, for ahead stands a pair of bridges, the first carrying the main railway line between Edinburgh and London. The second is a long, dark tunnel above which the broad carriageways of the A1 run.

The Portal

It is like a portal to another world, a world of burgeoning nature, of history, of imagination. Once through the tunnel I follow the grassy track uphill and along the top of a wood bright with primroses and wild daffodils.

The Grassy Track

The burn is now down below and I can just glimpse its gleam through the trees. At the edge of the wood I go through a gate and there over the fields before me is Doon Hill, its steep northern face cloaked in tracts of gorse.

Doon Hill

Once over the next field, freshly harrowed and spring ready, I climb over a wooden fence and find the way up through the gorse. The climb is steep but short. At the first ridge I stop and look down on the valley below.

What I see is the site of the Battle of Dunbar, which took place on the foul morning of September 3rd. 1650, after ‘a drikie nyght full of wind and wet’ in the words of one hapless Scottish soldier. It was the year after the beheading of Charles I by Parliament and the country, led by Oliver Cromwell backed by the New Model Army, was declared a Commonwealth. The Scots were not inclined to agree, however, and regarded Charles II as their rightful king. To set matters right Cromwell advanced upon Scotland. His first attempts to penetrate the seat of power in Edinburgh failed. His army, around 16000 men, was weary from long marching and hungry. Cromwell withdrew to Dunbar and set up camp at Broxmouth, on the low ground between Doon Hill and the sea. The Scottish army of some 22000 men, commanded by David Leslie, pursued him there and took up a position on Doon Hill, a seemingly advantageous point from which Cromwell’s movements could be monitored and his supply routes cut off.

The initial disposition of the opposing forces

However, due to the strategic incompetence of Leslie’s superiors, the Scottish troops left their vantage point and moved down the hill to confront the enemy on the other side of the valley. In disbelief Cromwell declared that the Lord had delivered them into his hands. He seized his chance and closed on the Scots in a surprise dawn attack. A messy battle continued through the day until eventually Cromwell’s superior tactics prevailed and Leslie’s forces disintegrated. About 3000 men were left dead and 10000 Scots were taken prisoner and marched to Durham where they were cruelly treated, left to rot in dungeons or shipped abroad as slaves. A recent monument, a block of stone overlooking what was the battlefield but is now a flooded quarry and cement works, bears the inscription, ‘In memory of the Dunbar soldiers taken prisoner near this spot during the Battle of Dunbar, 1650. Their remains were discovered in a mass grave in Durham Cathedral and were laid to rest in May 2018’.

Cromwell’s legacy is still visible in street names around Dunbar and the old harbour, the Cromwell Harbour, which was extended during his time with funds from his government. A small hillock in the grounds of Broxmouth House is called Cromwell’s Mount.

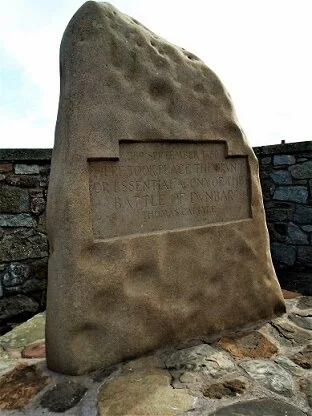

Another lump of stone commemorates the battle, embellished with the words of Thomas Carlyle, ‘Here took place the brunt or essential agony of the Battle of Dunbar.’

A few minutes more and I am on the broad top of Doon Hill. A cairn marks the spot but the true summit is the trig. point standing in a ploughed field a little distance away. I take in the view, a panorama with Dunbar at its centre. The coast stretches westwards over Belhaven Bay to the volcanic outcrops of North Berwick Law and Bass Rock,. The view to the east is not particularly uplifting, dominated as it is by the cement works and the nuclear power station beyond, but further down the coast, towards England, the cliffs rise ever higher, culminating in the spectacular craggy shoreline of St. Abb’s Head. Then I turn and look to the south over the rolling landscape to the misty line of the Lammermuirs proper.

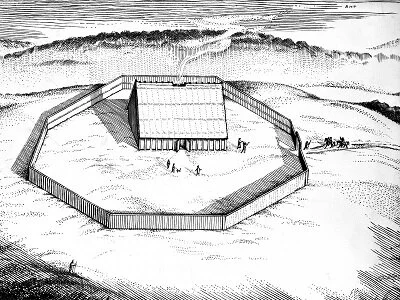

But much closer, only a few yards away in fact, is a flat area holding another aspect of Doon Hill’s history. In the 1960’s aerial photographs revealed signs of early settlement and archaeological work began. It turned out to be the site of an Anglo-Saxon hall which probably belonged to some Northumbrian lord, for this part of the world was then in the kingdom of Bernicia, later to be called Northumberland. More remarkable still, it appears to have been built within the boundaries of an older, even larger hall, dating from the sixth century and of a different architectural style. This hall may have belonged to a British tribal leader. Evidence showed that this hall was burnt down and the later hall erected in its place. The hall was surrounded by a polygonal wooden palisade.

It may have looked like this….

Now, the outlines of the two halls are helpfully demarcated on the ground by concrete strips, different colouring for each one. I wondered if the inhabitants of the Anglo-Saxon hall were aware of the words of one of their contemporaries, as recorded by the Venerable Bede. He compared the life of a man to the flight of a sparrow, entering from the darkness into the cheer and warmth of the mead hall only to pass swiftly out of the other door into the wintry night without.

History goes even deeper here, though. During the excavations, evidence of extensive cremation burials came to light, dating back to the late Neolithic and Bronze Ages.

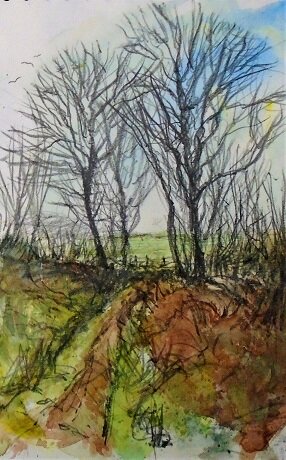

Lingering a while at the site I am once again struck by a sense of the passage of time and the brief journey of us mortals through it. I feel a brief shiver in my spine as the breeze gains an edge and I turn to go. I am not going down the way I came up. I prefer circling, so I climb over a gate to the south of the hilltop and descend down the side of a neatly ploughed field with its rich, red soil, then follow a wall down to the environs of Spott House.

The Way Down, looking South

I find a convenient perch to sit and open my coffee flask, under a tall pine tree. Spott House is well hidden but its fairy tale turrets and spires can be glimpsed through the trees. It is built in the same style as nearby Tyninghame House. The so-called Baronial Style was popular in Scotland in the early 19th Century and its chief exponent was William Burn who designed both Tyninghame and Spott. There was an earlier 13th Century house here, occupied by noblemen descended from the Norman barons to whom William the Conqueror parcelled out his newly acquired kingdom. In more recent years, country houses and their estates have appealed to the newer rich — wealthy business men, pop stars, foreign shipping magnates who fancy adopting the lifestyle of the Scottish laird. One such, a Danish businessman, occupied Spott House for a time. When he left, the house, like others of its kind, was split up into separate apartments.

Spott House, glimpsed through the trees

I leave the spires of Spott House behind and start back around the foot of Doon Hill’s steep northern side, wooded and blanketed in gorse beginning to blaze yellow. I look up and see the pale sun gleaming through the trees. Across the fields below is what used to be a farm but is now a cluster of privately owned cottages. There remains, though, a tall chimney. There are several such around the farmsteads of the Lothians. I recently found out that they are the survivors of steam threshing machines which were powered by coal from the rich seams to the west, towards Edinburgh.

Old Chimney

Soon I complete my loop at the fence I previously climbed over, cross the fields, follow the track along the top of the wood and approach the dark tunnel. I pass through and under the railway bridge to emerge by the stream flowing bright and clear, back home, back to the present.

Doon Hill from the South