Inscapes

I once had a local exhibition which I called ‘Inscapes’. It was based on drawings and paintings inspired by a scrubby area of land on the edge of Wakefield known as the Washlands. Nature was gradually reclaiming what had not long before been an industrial wasteland, the remnants of a coal mine, gravel pits and lagoons for the dumping of ash slurry from the nearby power station. The place was enclosed within a loop of the River Calder and a ruler-straight length of the Aire and Calder Canal. I walked there often. A place of little lakes where the gravel pits had been, hidden runnels and small ponds, reedbeds and scrub and young woodland — birch, oak and willow. And in the background the continuous roar of Kirkthorpe Weir.

The Weir

For me it was a place of reflections, and reflection. A fair body of art and poetry emerged from it. I stole the word ‘inscapes’ from the Victorian poet and priest, Gerard Manley Hopkins, who invented the term ‘inscape’ to denote the essential, individual quality of a thing — he seems to have reserved the word for natural, organic ‘things’. This essence he communicates in the rich cadenzas of his poetry. Here, from ‘The May Magnificat’, he celebrates the new growth of Spring:

Flesh and fleece, fur and feather,

Grass and greenworld all together;

Star-eyed, strawberry-breasted

Throstle above her nested

Cluster of bugle blue eggs thin

Forms and warms the life within;

And bird and blossom swell

In sod or sheath or shell.

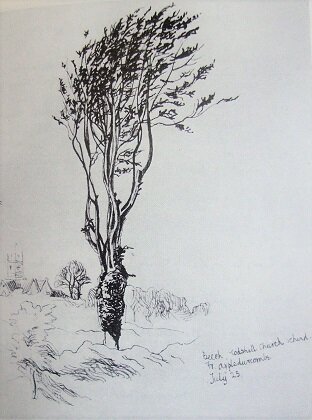

Hopkins was much influenced by the medieval theologian, Duns Scotus, whose word for that essential nature was ‘haecceitas’, best translated as ‘thisness’. Hopkins, on observing a tree, wrote in his journal:

‘There is one notable dead tree….the inscape markedly holding up its most simple and beautiful oneness up from the ground through a graceful swerve below (I think) the spring of the branches up to the tops of the timber……I saw the inscape freshly, as if my mind were still growing….’

Hopkins’ drawing of a tree

The driving force behind ‘inscape’ was, of course, for one of his religious leanings, God. The expression of ‘inscape’ he called ‘instress’, a sort of divine energy which unites the observer and the object in a divine revelatory experience.

Gerard Manley Hopkins (1844-89) and Duns Scotus (1266-1308)

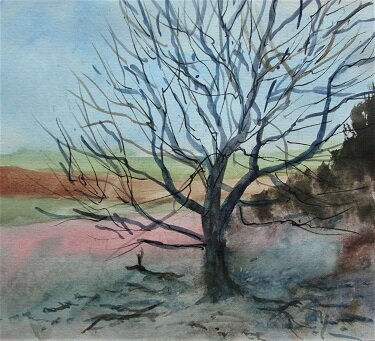

I am grateful to Hopkins for coining that word, ‘inscape’. I understand what he’s getting at, but I make no apology for pluralising it and interpreting it in my own way. Here is a tree I painted:

Tree

It stands on the edge of a salt marsh and once, as I was standing under it, a flock of goldfinches alighted in it and filled the air with their glittering jingles. So that tree is infused in my mind with my experience that day — the place, the light, the shape of it and, of course, the goldfinches. Nevertheless, the tree is a tree is a tree. It has its own uniqueness, of course, as do all living things and this is down to the complexities of the evolutionary process. But there is nothing supernatural about it. If I were to put a sliver of the tree under a microscope I doubt if I would detect God in it.. So the ‘inscape’, for me at least, is all one way. Like all human beings, I presume, I feel impelled to seek pattern and meaning in my experience. What is happening, I think, when I respond to nature is that the thousands of threads in the neural networks which inhabit my brain shift and click according to the algorithms of what makes me me — my genes, my history and education, my environment, my personality, even my present mood or emotional needs — to produce a particular sensation, a sense of wonder and beauty, perhaps, or something more shadowy, tinged with melancholy.

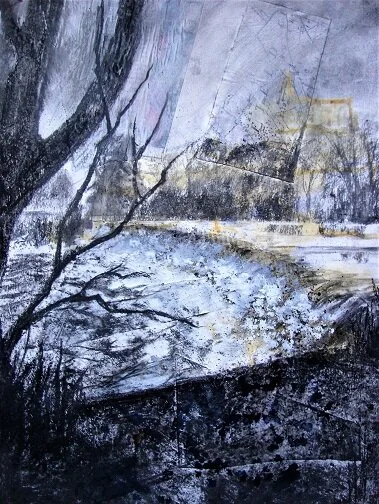

It is that sort of sensation that I was trying to express in my ‘Inscapes’ pictures.

Washland Sun 82x58cm

I didn’t want to just represent the view, though there is nothing wrong with that, but wanted somehow to get inside it. As part of this process I made extensive use of collage — physical layers to reflect the various facets of my ‘inscaping’! The first series I did on square boards onto which I stuck bits of vegetation, handfuls of ashy grit and fragments of rust gleaned from the site itself. I painted with a mixture of oils and acrylics and produced four pictures to represent the equinoxes and solstices of the year. Here is ‘Vernal Equinox’, the most seasonal at this particular time.

Vernal Equinox 60x60cm

A further series was a set of large drawings which I prepared with vertical strips of newsprint and other papers stuck onto the cartridge paper and coated with white emulsion. For some reason I painted a splash of watercolour before starting the drawing. I used graphite sticks, charcoal and black soft pastel for different levels of tone, also an eraser to lift areas out and to spread the dark dust around.

Washland Reeds 82x58cm

Washland Reflections 82x58cm

The Washlands were indeed for me a place of reflections. Sometimes, working my way through the scrubby undergrowth, I’d come across a patch of marshy ground where I couldn’t make out what was material and what was reflection. And somehow this fed into my own mental reflections…where am I, who am I, what is real, where is love, and so on and so on and so on…….

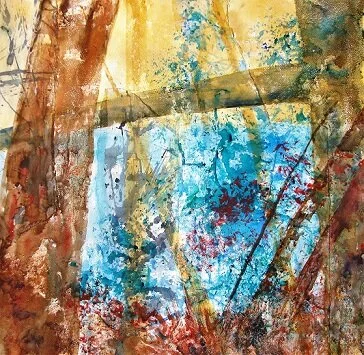

Then came a series of more abstract paintings, again using scraps of paper collage but this time applying wet watercolour, allowing it to run and mix, sinking into the torn edges. Then I worked in suggestions of trees and vegetation, trying to show the shifting boundaries of light and substance which again embodied the shades of my own response.

Washscape 1 56x38cm

Washscape 3 56x38cm

I always took my camera on my walks round the Washlands and when I got home and examined my catch, I’d sometimes zoom in on a photo and crop it to produce an abstract image. I made some paintings from these images which I actually called ‘Inscapes’ since they were close up entries into the scene, inner-scapes, as it were. These are two preliminary watercolour studies for what later became acrylic paintings.

Another element of ‘inscape’ is the past, and here in the Washlands were ready reminders of a not too distant industrial history: the gravel workings, the mine — Parkhill Colliery, the stretch of river re-routed to make way for the railway, the bridge carrying the slurry pipes across the river, the weir, an old iron winch deep in the undergrowth…

Winch

Tunnel

Beneath the hefty thud of goods,

you tunnel through

from ashfield to birdsong unravelling

among osiers, grit

crackling under your bicycle tyres.

The air is edgy with echoes

…rattle of winding gear

diggers grunting

in the gravel beds, slush

of slurry down foot-wide pipes.

Resting on the bank

you watch the river’s heavy weight

slide by to spill out at the weir.

History stirs and swells,

eddying among reedbeds.

You sense your bones

are something felt in, undefined.

The hours pass like clouds

until you wake,

the sand unsettling in your eyes.

For Gerard Manley Hopkins, ‘inscape’ was the essential thisness of a thing, showing the glory of God’s creative energy. When the observer grasps this thisness he shares in that God-ness. A potent idea. For me, ‘inscape’ is a searching into something for meaning and significance, for something which resonates with my inner landscape, my mindscape, and feeds my need to affirm who I am.

I recall a voice from somewhere, deep in the woods, perhaps….’I don’t believe in anything. I just have experiences.’

Washlands