Album Leaves

My last blog contained two poems, one about my father, the other my young grandson. The waves breaking along the shore became a metaphor for the passing generations. They threw up an array of kaleidoscopic images, fragmentary episodes marking the fleeting decades of that slice of my family history that I am still aware of., the rest of it drowned in the vast ocean of oblivion.

The Waves break on the Shore

The flat levels of the Lincolnshire fens. We have driven up in the Austin 16 from Buckinghamshire where my father works on a farm. His family have for some reason decamped from the mills and smoke of Bradford to the airy spaces of Lincolnshire. My grandfather rides a huge three-wheeler along the long straight roads. A green bus takes my grandma to the market in Boston. Today we are going down the road to visit my father’s grandmother. I am nine. A little wooden bridge crosses the dyke. The path leads to a red-brick house, a garden and a long chicken-run. Great-grandma is in bed. She lives there. Great-grandad is with his hens.

‘Go up and see your Great-gran now,’ my mum said,

then that flinch of nerves as we entered

the moth-balled sick-room curtained from the day.

Propped against the huge bed-head

she lay shrouded in black — I thought of

a monster crow, its wing folded around her.

I queued behind my sisters

till the pale claw-finger beckoned,

then the floor creaked as I bent

to kiss the cold parchment cheek.

I couldn’t wait to tiptoe downstairs

wiping the dust from my lips and burst into the sunshine,

scattering gravel as I ran to the hen hut.

There, in a brew of creosote and pipe-smoke,

sat Great-grandad in his brown overalls, deep in chicken shit.

He winked and fetched the tin of pear-drops

from the shelf. While I sucked,

I listened to the gurgle of spittle in his briar stem

and watched the wreaths of blue

feathering upwards in a shaft of light.

Seated Man

A word of warning. Memories are not attested fact. They are inventions. Just as we each watch the world through our own individual periscopes, filtered through the prism of our uniquely skewed perspective, so our memories are personalised versions of the past, shaped by our own peculiar experience. So the poems which make up this family album must be read as fictions, not historical documents.

At the farm

The owners of the farm where my father worked sold up. A horse-breeder bought it and intended to turn it into a stud-farm. My father knew nothing of horses so we had to move. We found a small plot of land in the bottom of a narrow chalk valley.

We are living in a caravan. There is a big wooden shed painted black where I play with my sisters and make nature tables like we have at our little school up the hill. I watch my father spreading out large sheets of paper on the floor. They are plans for a bungalow.

His Shirt

An old photograph, curled at the edges.

Me in the big wheelbarrow, grinning.

Behind, pushing, my father, thin as a hoe,

squinting at the sun, his forearms tense as steel.

Clothes that stitched him to a generation —

those baggy corduroys held up with twine,

the sleeveless V-neck tucked in at the waist.

And then the shirt, thick flannel, collarless,

sleeves rolled tight above the elbows.

But it is his back I see now

in a glare of summer heat,

the gleam and trickle of his sweat

as he bends into his shadow,

slugging away at the unforgiving clay,

the warp and weave of his sinews

flexing under the glistening skin.

And me, crouched in the dark

of the hawthorn hedge, clutching his shirt.

Already there was a distance between us which only widened with time. I think, in those days when he was hacking away at the hillside, he was venting an intense anger at the world, his situation, himself. The bungalow was never built. The marriage was beginning to unravel too. There were rumours involving a barmaid at the Rose and Crown. My mother, an intelligent, sociable, public-spirited woman — she ran the local Brownies among other things — must have wondered how she ended up in a caravan stuck in a lonely, dry valley.

I am playing on the common up the valley side, my imaginary wild west, when I break out onto the path.

Mum

Summer sizzled and I played

on the common above the dry valley.

Ferns were my forest and the sun

strobed through the leaves.

But I spilled out into the steep path

and my mother coming up,

grim faced in bonnet and overcoat.

She carried a brown suitcase.

‘Where you off to, Mum?’

‘Sod you,’ she said and dragged me back

down the hill. She sent me to bed

at the back of our caravan.

My skin was branded with shadows.

I longed for light and the open air.

Later she brought me some milk

and sat on the step and wept.

Life Class

I reel back a generation to her parents. Just as my father’s family had removed to Lincolnshire, my mother’s side — Scots all — moved down from the Central Belt…Ayr, Glasgow, Dundee…first to London where my grandad, formerly a riveter in the Clyde shipyards, took advantage of the new opportunities at Ford’s in Dagenham, then to Buckinghamshire. Perhaps families do not follow each other around as much now. When sons and daughters started flitting far and wide to colleges and universities they savoured an independence which has remained with them and, in my experience at least, has served them well. My family currently has map-references in East Lothian, Dorset, Yorkshire, Cambridge, Brighton, Oxfordshire and County Cork.

Grandma and Grandad

Grandma is all warmth and comfort, always in her apron and brewing yet another pot of tea. Her death takes everyone by surprise. My aunt comes round to report it.

Grandma

She hugged me when I went round,

folding me into her warm apron.

She showed me how to shell peas

and peel a cooking apple in one go.

I fetched her milk and margarine

from the cool pantry, then took turns

stirring the stiff cake mixture.

Afterwards she let me lick the spoon.

When I left she hugged me again,

delved in her purse and gave me a sixpence.

She was out shopping with Grandad

when she fell down by a lamppost, dead.

Grandad walked on, chattering to thin air.

My aunty told us. She sat on our sofa

and wept into a little white handkerchief.

I sat on the floor pushing my Dinky cars

around her stockinged ankles and light brown shoes.

My mother put the kettle on.

After the funeral, strange relatives

in dark clothes nibbled slices of pork pie

from the sideboard and patted me on the head.

Grandad sat in the corner. He never drank

but Uncle Jack filled him with sherry.

He giggled through his tears and asked for more.

That night in bed I played my plastic clarinet

until I dozed. I turned the light out

and slid into the warm folds of my sheets.

I was falling asleep when the wardrobe moved.

The door swung open and Grandma stepped out.

She smiled and moved towards me.

‘Here’s your sixpence,’ she said.

I tried to take it, but she was out of reach.

Alone now, Grandad lived in a small terrace house smoking his pipe and fiddling around on his kitchen table with his soldering iron. He also, to my delight, made model sailing boats which, magically, he put inside little bottles.

Reflections

My parents met in the war. They both served in the Far East, my mother in the WRNS, my father in the RAF. They got married at the end of the war in what was then Ceylon. Like many of their generation they were inveterate smokers. I think that had a lot to do with their demise. Though separated for many years, in the end they both died of cancer.

My mother at Luccombe Estate in Ceylon where she was stationed

My mother spends her last days with my sister near Huntingdon. She is very frail and lies quietly in bed. The sun is shining — she wants to go out for a drive. In the gently rolling countryside is a small village known for its maze….not a full-on labyrinth of tall hedges, just a pattern of paths mown into the grass.

The Maze

On the last day she wanted the maze,

oddly for one so direct. I lifted her

into the car, a sack of twigs, the ‘Pastoral’

on the cassette — ‘Awakening of Happy Feelings’.

She hummed along in the back.

I looked in the mirror, saw the sky in her eyes.

The A-road surrendered to hedges and farm gates,

a lane through a tunnel of trees,

until the village and its hidden green.

Swallows circled, skimming the grasses

as I cradled her along the devious

paths shaved into the clover and herbs.

I searched out wrong turns, lingered down dead-ends.

‘There’ll be no cheating, mind,’ she fluted back,

her syllables straight and narrow.

‘As if I would,’ I whispered, for this was the closest

she’d ever been, and the lightest.

I paced out the turf this way and that

and found the centre. She smiled

as if she knew. When I turned to go,

‘Let’s stay,’ she said, a dry laugh on her lips.

There was no going back, it seemed,

so I held her through the still afternoon,

rocking her to birdsong and the scent of thyme.

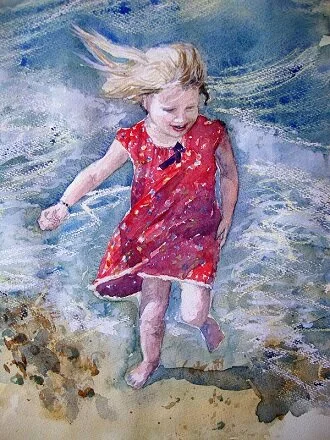

Surf

Those generations have gone under, swept up in the current’s undertow. I, we, my contemporaries will be next, and this is where, for the time being at least, this family album closes, except for a postscript.

The Greek temple in the woods, lit up in the gathering dark. The drama students are dancing, weaving amongst each other in the torchlight, in their flowing attire.

Going Back

Here in the temple in the wood

between the columns and the torches

I watched you dance.

Your limbs were woven with the shifting light

as you arched and flexed

bending to the sound of flutes.

Then you reached out and turned my bones to love.

Now, beyond the ‘No Admission’ sign,

only the scattered stones.

Standing under the dripping trees, mist-bound,

all I can hear is the motorway’s white noise.

Moving Colours

Though long apart, we were together for over twenty years, and even as our own parents gave way a fresh generation surfaced, as it is wont to do….a daughter and two sons, all now going their independent ways.

I am in Wakefield Cathedral, sheltering from the rain. My daughter, living in Edinburgh, is pregnant. She has sent me a blurry black-and-white photograph. Later, on the phone…

…you said, ‘It’s my scan.’

There under the skin

a grainy image

like a fingerprint smudge

in gleaming moondust —

and hung in its luminous nest

a tiny bean of love.

‘It’s waving,’ you said,

and this little life

became in my head

a bead of pure light

like the flame of the candle I lit.

Long may it burn

For you, my bairn,

And the one to be born.

The bean turned out to be Martha, the first of my six grandchildren. Suddenly, those images of parents, grandparents, shrink back into a sepia past and the present lights up with a digital confetti of Facebook shots for the album — or the folders marked ‘family’ on the laptop. I feel blessed, if at times somehow undeserving. Despite the undercurrents, the rocky hazards, the shipwrecks and that deep sigh as the sea withdraws, the waves keep breaking as generations hasten forward on the flood of time.

Her Funtime Book

On the white sand….my granddaughter

lying with her Funtime Book,

and her mother behind sunglasses reading.

Then her mother under a parasol, dreaming.

And I think of my mother paddling in the shallows,

her skirt hitched up.

In this heat and sleep it’s hard to grasp,

when also in the picture is the gull’s

steel eye feeding its ancient appetite,

the thrift pink again in the sea-wall,

and that white shell lodged

in centuries of rock.

So I watch this child,

the latest wave lapping her feet,

join up the dots in her Funtime Book.

Martha in the Waves